Kicked in the Head

Kicked in the Head

An interview with Matthew Harrison

by Michael McCarthy

Getting Kicked in the Head

I recently had the pleasure of attending the U.S. premiere of writer/director Matthew Harrison’s third film, Kicked in the Head, at the Boston Film Festival. Just listening to his introduction, it was evident that Harrison is more than a bit passionate about filmmaking. This was confirmed during the Q&A session he hosted after the film. While each of the Q&A sessions I’d attended during the course of the festival was interesting enough, there was something different about Harrison. Something inspiring in the way he speaks about films. Something that made me want to talk to him. I introduced myself and an interview was promptly set for 10:30 the following morning.

The interview took place in just over forty-five minutes. Forty-five minutes of fast-paced, rapid fire conversation; further evidence of the excitement Harrison possesses for filmmaking, the same excitement and enthusiasm that shines through Kicked in the Head. An enthusiasm I’ve not witnessed since, well, the first time I caught a television interview with Quentin Tarantino just before Pulp Fiction was released. The comparison, however, stops there. As you’re about to learn, Harrison is an original.

First of all, I understand your last film garnered you a lot of praise.

First of all, I understand your last film garnered you a lot of praise.

My second feature was a picture called Rhythm Thief about a music bootlegger. That won the Jury Prize at Sundance in ’95. It got picked up and we had a release in the U.S. and Europe. That got even more critical acclaim than my first film, Spare Me. The important thing with Rhythm Thief is that Martin Scorsese saw a copy of it when he was shooting Casino in Vegas. He liked it very much. He called me on the phone and that’s how Kicked in the Head came to be.

Has Rhythm Thief or Spare Me been released on video in the United States?

Rhythm Thief is coming out on video at the end of September on Strand Releasing. I did my own release for Spare Me. It’s in video stores in L.A. and New York. I’ve got to make sure it gets into some video stores in Boston.

Was Kicked in the Head with October Films to begin with or did they acquire it later?

They were really interested in Spare Me, and then I didn’t give them Rhythm Thief, but they wanted to be involved in that. Something told me we had to do it ourselves so I could have total control. And we did. Then they were like, “We really want to work with you.” Other companies did, too, but October was the most enthusiastic. So, boom, it went to them. They really became involved from the getgo. The movie belongs to them.

Martin Scorsese’s credit is executive producer. What was his involvement once the wheels were set in motion?

Marty was really helpful in the casting, which is critical for a film. I mean, that’s how a film gets made, really. And he was very helpful in assembling the crew. He wanted to know who the cameraman was, etc. But Marty was very hands off, which was great. I would ask him, “Marty, what should I do about this?” He would say, “Well, you do what you want. You’re gonna know what you want to do. Just think about it and do it.” And then when we were cutting the film, he gave me notes on that. Places where he thought we could adjust things. So, that was great feedback from him.

Were there instances where you’d filmed actual alternate versions of scenes?

Yeah. Like places where things were really turning around for Redmond. We did a version that went very much this way and a version that went very much, emotionally, that way. Then we kind of balanced things out. So, when Marty said, “The scene where Linda tells him to leave, I think you went a little too far with Redmond getting upset. Can you back off on that one?” We said, “Yeah. Kevin and I shot a version where we kind of changed his experience.” The other place where Marty was really helpful was at Cannes. Marty really introduced the film to the international filmmaking set. People said, “Mr. Scorsese, why are you here at Cannes?” And he said, “Well, I’m here at Cannes with Kundun and Kicked in the Head and this is Kevin Corrigan and Matthew Harrison.” That was great, you know? He really was our godfather there. He’s my mentor.

Bruce Williamson of Playboy said “Martin Scorsese produced Kicked in the Head, which means you certainly have talent,”which made me wonder if you feel people might expect too much from you because of his involvement.

Bruce Williamson of Playboy said “Martin Scorsese produced Kicked in the Head, which means you certainly have talent,”which made me wonder if you feel people might expect too much from you because of his involvement.

I recently got a list of, like, 40 magazine critics. I noticed all these names of heavyweight people and I’m like, what the fuck? This is really not appropriate because this film is for younger people. I think the senior critic said, “Oh, here’s the Martin Scorsese one, I’m gonna take that one.” The junior critic said, “But I want to do it.” But the senior’s like, “No, no, no, I’m gonna do it.” And then they go in there like, “OK, I’m gonna take Marty down a notch.” I’m like, man, that was a bad move on the part of the PR firm. They’ve been sending stuff out with “Martin Scorsese” in big letters across the top like, “This is great, isn’t it? We’re gonna get you some press.” I don’t think that’s such a good idea, you know? I remember Marty saying that to me once. He said, “A lot of people might come gunning for you because of my name.” I was like, “Well, what the fuck, I don’t give a shit.”

This is the first time you’ve had significant money to play with and “stars.” Did it feel different making this film, like making a debut again?

Yeah, it kind of did, but I tried to really avoid that. I tried to downplay things a little bit. I think that’s why sometimes the script takes a left turn when you might expect it to take a right. It has more important things to do. I’m continuing to make films. I’ve got to be true to myself.

Kicked in the Headtakes place in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Was it filmed entirely on location?

That film was entirely on location, the Lower East Side streets that I knew. The building where Stretch lives, I lived in that building in that same apartment. The scene where they’re eating Chinese food – that’s the table where Kevin and I wrote the script. So that’s all authentic. And the streets around those projects are where Redmond was walking. That’s where we shot them.

So, you had the specific streets in mind when you wrote the script?

So, you had the specific streets in mind when you wrote the script?

Absolutely. Like the bagel shop where he steals the car in the beginning – that’s all the six block radius from where Stretch lives. It’s all the same area.

Did you encounter resistance from the producers and such in regard to filming on location in New York as opposed to going to Canada?

Marty and Barbara [De Fina] said, “Where do you see this?” At first they were like, “What are you talking about? We know this great building in so and so and we know these other great streets in so and so.” I was just like, “No, no.” And I kept pushing for these locations. Kevin and I took my little video camera and we just did a walk of the whole neighborhood that we’d written the screenplay about and gave them the videotape. They all went, “Whoa, OK, hey, it’s done.” It worked out really well.

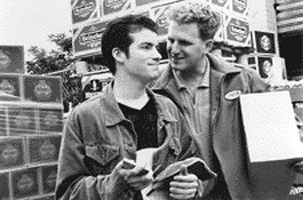

You co-wrote the script with actor Kevin Corrigan. What’s the background there?

Jason Andrews, the guy who plays the lead in Rhythm Thief, introduced us. Kevin grew up in the Bronx and I grew up in downtown New York City. We just hit it off. We spoke a lot of the same language and we had a lot of the same experiences growing up. That was exciting. I started thinking I wanted to come up with an idea for a film he could play the lead in. And after we shot Rhythm Thief, he was going through this break up with his girlfriend and he’d run out of money again and lost his apartment. He would talk to me for hours about how he felt. It brought me back to that feeling of being in your early 20s, mid 20s, where it feels like you’re doing everything wrong. Everybody says you’re a fucking loser, you know? “Get your fucking life together.” You’re trying so hard, but none of it seems to be working. It was so vivid listening to Kevin talk about it. It just made it so clear again because he’s a really emotional person and you can see everything in his face. I kept telling the cameramen and the art people – everybody on Kicked in the Head – all we’ve got to do is get Kevin’s face. That’s the movie.

What was it like directing him after he’d written the script with you? Did either of you show up and find that the other had decided some things should change and disagree?

Like any relationship, in the beginning of a film, you have to have your blowup. You just have to do it, get it out of the way, and then it’s cool. But a lot of that was just creative tension. There’s a lot of trust. I feel really lucky to be working with somebody like him who cares so much about the work. He puts so much of himself into it. He’s not afraid to just completely be vulnerable and bare his soul, you don’t find that very often.

Was there a certain past performance of Linda Fiorentino’s that inspired you to cast her as Megan?

Was there a certain past performance of Linda Fiorentino’s that inspired you to cast her as Megan?

Actually, no. I didn’t watch Last Seduction until, oddly enough, the wheels were already in motion. I had seen her in Desperate Trail. For some weird reason, I taped that off HBO. It’s not a particularly good film, but I thought she did some great things in that. Mostly, it was here are some people on a list – actresses that I went over, Marty went over, Barbara went over, October went over – and then we said, OK, let’s start. Then the script goes out. It’s really about who is going to respond to the material. What’s the point in talking to somebody unless they really respond? Linda came right away and was like, “I really like this. I want to do this.” Then I looked at Last Seduction and was like, whoa! I could see why she really wanted to do this because a lot of what she did in that part parallels.

Was there any fear directing James Woods where he’s a friend of Scorsese’s? Like he might call him up and ask him what he got him into?

No, Jimmy was cool. That happened really quickly. We were struggling with casting Uncle Sam and one day Barbara called me up and said, “Hey, Matt, what about James Woods?” I was like, “Oh my god, why didn’t we think of that before? That’s brilliant.” And she said, “OK, go meet him today.” I went there and he said, “I’m not doing a lot of pictures anymore. I’m only picking a couple good films a year. I read two good scripts, your script and Rob Reiner’s. I want to do it.” We talked and got a feeling for each other. He said, “Well, hey, have them make the offer today.” They did it and he came on.

What was he like on the set?

Jimmy really likes to work. He loves to be involved in it. Linda was like the opposite. Linda was like, “Don’t worry guys. I’ve got it all figured out. I’m gonna be in my trailer. Call me when everything’s ready to go. I’m gonna come out, I’m gonna do it, and I’m gonna go back in.” But Jimmy was like, “Hey, what are we doing? What’s this? What do you guys think of the coffee?” He wants to hang out.

Michael Rapaport is absolutely hilarious as Stretch. A real scene stealer. Was his fast-talking dialogue improvised?

That was all written. But the thing with Mike was that he’s a friend of Kevin and I. Mike really wanted a part in Rhythm Thief, but he came a bit too late. So, Mike was somebody who Kevin and I decided we wanted from the beginning. Mike would come to the apartment and fuck around, talking about his character. He walked around the room and went, “This is my house! My house!” And he said, “I want him to water the plants. And I want him to be over here in the kitchen telling Redmond everything about life and how he should do it.” You know, the way he gets into that one spot and is like, “It’s gonna be like this, it’s gonna be like this, it’s gonna be like this.”

What inspired the Hindenburg footage that you’ve inserted in different places throughout the film?

What inspired the Hindenburg footage that you’ve inserted in different places throughout the film?

I was always interested in the Titanic when I was a kid and Kevin was really interested in the Challenger. I’ve noticed that there’s a certain age when kids start to get really interested in big disasters. They become obsessed with the Titanic. They want to talk about all the people who died. I proposed to Kevin that we should have Redmond be interested in a disaster. For a while we were thinking of the Challenger, but then I said, Kev, what about the Hindenberg, because it’s a pretty amazing visual. The flipbook is what did it. You play it over and over. There’s that point in your life where that disaster seems to become solace. But then you realize every fucking day I pick up this Hindenberg flipbook, I look at it, and I get a jolt of that feeling. And, you know what, I can take that book and put it in a fucking drawer, close it, and I wouldn’t have to feel that every day. But you don’t figure that out until you’re a little older.

I understand you didn’t go to film school. That said, how did you learn the basic mechanics of directing?

By making a lot of movies, mostly. I just consume a lot of information about making film. It’s amazing how much you can learn from books about excellent directors and by watching their films really carefully. The mechanics of making film? There are a lot of people out there who are way better at it than I ever will be. My job really is to keep us on track emotionally, which is very hard to teach. One of the first people to really tell me I was on the right track was Martin Scorsese. I used to go to different seminars and hear people talk. I always felt like, oh man, I’m really an idiot, I don’t know all this stuff, I’m doing it all wrong.

He gave you that grand stamp of approval.

He gave you that grand stamp of approval.

Yeah. The great thing was he told me, “You’ve been going about it the right way. You’re onto the right shit. You’re onto the shit that really matters.” I’m not a filmmaker who follows. When I was young, I realized the only thing I could ever do is build my own little world. I started making films in 1969 when I was nine years old. There were lots of clues in Kicked in the Head that relate back to films that I made in the early ’70s, mid ’70s and the early ’80s. People who know my work understand the little clues and messages. I try to balance that out by making my work as accessible as possible to everybody so that I can have a wider audience, but I also realize the thing I can really give to people is to be completely true to myself as an artist, as a filmmaker, because if I’m not you can feel it in the work. I view that as a commitment. It’s really hard to keep, actually. There’s a lot of pressure.

Have you been getting a lot of offers to do films that you don’t want to do?

Mmm-hmm. But I don’t really entertain them much. I’m sure that pretty soon some really great writers or producers I admire will come to me with really great scripts, and that I’m looking forward to. That will be interesting. As it is now, I develop my own material pretty exclusively with other writers and myself. They like to grab film directors nowadays at 26. I realize that it would have fucked me up big time, as a creative person. I look at the stuff I did when I was that age and I realize, man, I just didn’t know enough. I didn’t have enough to say yet. I could certainly have had a bunch of young, sexy actors running around in hip new clothes, using hip new slang, with hip new music on the soundtrack, but no way, man. I was interested in ideas. So, I chose the route I did and I’m glad of it. I didn’t realize the strength of the position that it would put me in later. Marty showed me that. You know, there’s Marty! I’m like, whoa, holy fuck, man! I’m not working with Fox Searchlight, I’m working with Marty Scorsese!

What are your expectations and hopes for Kicked in the Head?

Kevin and I really made this film for all the Redmonds out there in the world. All the young men and women who feel like that. So they could feel like they’re not alone. It’s pretty damn funny when you go through that stuff and then you look back and you’re like, what was I doing? (Laughs) That’s my hope, that they all get to see Redmond, everyone who’s felt like that and people who remember what that was like. I just hope that everybody who needs to see it gets to see it.