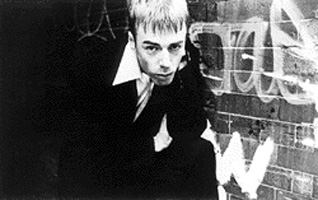

Momus

Momus

Ping Pong (Le Grand Magistery)

An interview with Nick Currie

by Nik Rainey

Greek God of Ridicule or English Cult Songwriter?

It’s safe to say that Nick Currie, the urbane Englishman also known as Momus, won’t be setting any worldwide sales records any time soon. Although an assured songsmith and one of the wittiest, most gifted lyricists working in the pop realm, Momus consciously sabotages his chances for major popularity by writing songs that comically play around with such taboo subjects as misogyny (“I Want You, But I Don’t Need You”), racism (“Space Jews”), and sexually-perverse psychoanalysts (“Professor Shaftenberg”: “Sponsored by Luftansa to screw the pants off Japanese girls”), with backing tracks that usually sound like they were made by pressing the pre-programmed default keys on a cheap Casio. Unsurprisingly, he’s all but unknown in the States: Ping Pong, his twelfth LP, is only the second to be released Stateside, the first being a b-sides/odds-and-odders collection, 20 Vodka Jellies (both on Le Grand Magistery). The songs, filled with sarcasm and willful perversity, are destined to raise the hackles of those bluenoses who may happen across Momus’ music. (Currie even takes on the subject in one of Ping Pong‘s funniest songs, “My Kindly Friend the Censor”: “I insert my (censored noun) into your delicate (omit)/and slide it gently down the whole length of your (unfit).”) Combining pop classicism with twisted, misanthropic lyrics is inspired in large measure by one of Currie’s heroes, Parisian pop pervert Serge Gainsbourg. “I discovered him about 1986 or so and just flipped. I loved that combination of seductive, ornately-arranged music with subversive and ambivalent lyrics, buying into pop culture but doing it as the pop artists did, with a sense of irony and fun, while being profoundly political. Serge seemed to be this sort of dandy provocateur, which is an interesting thing to be.” Ping Pong‘s songs, written in the voices of different, unpleasant characters , are rooted in a satirical tradition stretching from Jonathan Swift (“His Majesty the Baby”) to the practitioners of the dying art of true “comedy music.” “I like people like Tom Lehrer or Randy Newman, who have a wickedly playful sense of fun in their songs but also manage to be more serious at the same time. Also, people like Leonard Cohen – he can be talking about very deeply spiritual concerns while playing some sort of crazy, surreal word game; silly on one level, but with a very profound subtext. But I think my humor’s a bit more to the forefront: I don’t think you can hear ‘His Majesty the Baby’ and seriously think I’m advocating infanticide.”

As the above indicates, Currie doesn’t write songs with an eye to the charts, and like many influential iconoclasts, others have taken his themes to far greater success than he has ever achieved – like Pulp, who once approached Currie to produce them, and have since gained renown with watered-down versions of his sardonic sensibility, which is fine by him. “I’m not that interested in being a mainstream pop artist myself – I’m more interested in keeping myself interested, getting into taboo areas and so on. I find Pulp’s struggle and obscurity more interesting than Pulp’s success. Jarvis (Cocker) is interesting because he had a kitschy, ironic take on suburban futility. But when that gets embraced by the very people who are suffering that futility, and gets interpreted as a celebration of it, I get a little uneasy. When you’re struggling, it means that you’re articulating something that’s uncomfortable to the dominant culture. In the proper terminology of the word, you’re subversive, and that always interests me, where being Sir Elton John doesn’t.”

All the same, he has infiltrated the culture in skewed ways, whether it’s the records he’s written for French chanteuse Laila France or Japanese pop nymphet Kahimi Karie, or the strangest tribute yet – a cover of his 1988 “The Complete History of Sexual Jealousy (Parts 17-24),” by Mr. “Do Wah Diddy” himself, Manfred Mann. “I know, that’s completely bizarre, isn’t it? It’s not a cover version I particularly like, but just the fact that these were the guys in black and white with pointy beards and glasses in the sixties, I’m very impressed that they’ve found their way to my songs.”

All the same, he has infiltrated the culture in skewed ways, whether it’s the records he’s written for French chanteuse Laila France or Japanese pop nymphet Kahimi Karie, or the strangest tribute yet – a cover of his 1988 “The Complete History of Sexual Jealousy (Parts 17-24),” by Mr. “Do Wah Diddy” himself, Manfred Mann. “I know, that’s completely bizarre, isn’t it? It’s not a cover version I particularly like, but just the fact that these were the guys in black and white with pointy beards and glasses in the sixties, I’m very impressed that they’ve found their way to my songs.”

And perhaps America will do the same, a prospect which, as a perpetual outsider, he welcomes with amusement. “My notion of America is that there is a maniacally optimistic experimental culture here. People are actually very pretentious, but in the best possible sense: everybody is into the idea of pushing the envelope of technology and art and lifestyles. I think the U.S. is rather an insane culture, which kind of corresponds to the manic cycle of depression: when you’re on the up side of that, you think anything’s possible, and you’re full of this rabid optimism. I feel that it’s both refreshing, but also a little scary and slightly insane, and that’s fascinating.”

Hmmm… can a grandiose concept album be far behind?