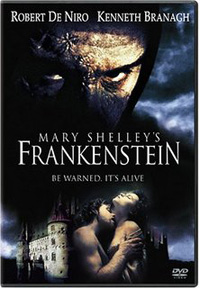

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

with Robert De Niro, Kenneth Branagh, Helena Bonham Carter

Written by Mary Shelley, Steph Lady, Frank Darabont

Directed by Kenneth Branagh

by Margaret Smith

I went to see this movie braced for yet another Coppola reign of terror over a beloved monster classic. Sure, this one was supposed to be really faithful to the original novel, but after all, so was that other film, the one with the Rocky Horror style, set and cast, and Keanu Reeves faking an English accent.

But for all those still tormented by memories of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein will serve as a healthy exorcism. Here, Coppola is the producer in name only; everything else is in the hands of sensitive actor/director Kenneth Branagh.

First, a disclaimer: Boris Karloff still rules, and old monster movies retain a poetic charm which no modern filmmaking innovations can ever supercede. But Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein eclipses all other previous efforts to reconstruct the story with faithfulness to the original novel and all its ominous implications for science. Young Swiss medical student Victor Frankenstein, played by Branagh himself, is obsessed with a quixotic quest to free humanity of disease and death. He finds an unwilling mentor in a teacher played by a shockingly serious, white-haired John Cleese. (That’s right, the John Cleese of A Fish Called Wanda, a Python called Monty, a ginger ale called Schweppes, a VCR called Magnavox…)

This professor has perfected the technique of using electricity to resurrect a dead arm, complete with a snatching and firmly grasping hand. The professor’s untimely death – coupled with a horrifying outbreak of cholera – only affirms for young Frankenstein the urgency of his mission. Completing the galvanization on a dead frog (which later left me wondering if this Frogenstein was still flopping around somewhere unbeknownst to the rest of the film), he then goes for the gold.

Using his deceased teacher’s brain, and borrowing generously from the suddenly ample piles of freshly dead furnished by the epidemic, Frankenstein, against the advice of his close friend (played by Tom Hulce of Amadeus), creates his opus.

This latest interpretation of the monster is an astounding cinematic feat, a combination of exquisite makeup design and the flawlessness of Robert DeNiro. Traditionally, the monster has been portrayed as a passive zombie, dependent on the whims of whoever gets to the Tesla coil first. DeNiro, however, plays the monster as the complex and often surprisingly articulate creature he is in the novel. When he is not avenging his abandonment by his master and his persecution by ignorant mobs, he enjoys befriending a blind man and playing a nice tune on the recorder. When he confronts Frankenstein after leaving a bloody trail littered with Frankenstein’s loved ones, he wants to know: who is he? Does he have a soul or is he just a glorified patchwork quilt? Where did he learn to play that confounded recorder anyway? Lastly, the monster is a mesmerizing contradiction of brutishness and stark charisma; as he treks alone across the snowcapped Alps in his long black coat, he is impossible to shake from the psyche. He becomes beautiful, and we wistfully accept that there will be no reconciliation between him and his uncontrollable rage against the humans who let him down.

No doubt DeNiro is the film’s stunning and deserving – and Oscar-worthy – centerpiece, amid a set and a cast which some have panned as trite and excessive. True, the nonmonster characters do a great deal of overemoting, with much shouting and flailing of arms and tearfully storming up and down long winding staircases. It’s an overexertion typical of Branagh, however, and it’s more than made up for by a great sense of balance everywhere else in the film. All the splendors of aristocratic eighteenth century life – grand ballrooms, brocaded dresses pushing womanly charms up and out, acres of lush estates overlooking breathtaking mountains – ride in tandem with the horrific poverty of those less fortunate of the era. The gore in this film – and splatterpunk fans take heart, for there is red sloshing and nasty crunching aplenty – is meted out unsparingly with merciless skill.

An analogy which came to mind in summary of this film was my feeling about Jurassic Park. In both films, there is a lot of mediocre acting and quite a bit of lofty reflection on whether humans have the right to give Godhood the old college try. In both films, the creatures who result from such meddling are so awe-inspiring that all other cinematic flaws become irrelevant. And although we come away moved and disturbed, we don’t ever feel preached to about the ethical dilemma of science. And because the creatures, despite the horrors they have inflicted, have made us love them, we wish – just a little – that it could have all worked out.