Godflesh

Godflesh

Songs of Love and Hate (Earache)

An interview with Justin K. Broadrick

by Paul Lee

For eight years, the duo known as Godflesh have been churning out harsh, bleak, and enraged music from the shores of England. Comprised of Justin K. Broadrick on guitar and vocals and G.C. Green on bass, Godflesh have just released the devastating Songs of Love and Hate (Earache). It may well be their best yet.

With a tour starting in November with a live drummer who may well be our own Ted Parsons (formerly of Prong), Godflesh is due to arrive in Boston on December 15 for a mere $7 show at The Rat! I had a chance to speak with Justin over the phone from England and get filled in on his perspective of the world, the music industry, and his definition of industrial music. For a man who creates such brutal vibes, I was amazed at what a friendly, polite, and lively interviewee Justin proved to be.

Songs of Love and Hate, what can I say, it’s great. I actually like it better than Selfless.

It’s much better. The goal for us was to make this album a lot better than Selfless anyway. Six months after the recording of Selfless, we weren’t very happy with the album. It turned out very dry, clinical. It was actually more down than we thought we were capable of. [Songs of Love and Hate] brought back the excitement and I think that’s what we were really searching for. This record has a lot more energy, a lot more excitement. It’s a bit more direct in its production and attitude, very live sounding. Selfless felt like we’d reached the peak of just guitar, bass, vocals, and a drum machine. We felt it was as far as we really wanted to go. It was the first record we made for Columbia in the States, and it wasn’t like the pressure was on to do or be anything, it was just on subconsciously.

I’ve talked to the guys in Napalm Death, and it seems like everybody had a bad vibe with that whole experience [Columbia/Sony distributing Earache].

Totally. But the one thing they did do was give us money and set us up, especially for Godflesh. We had our own studio anyway, but it was a very small studio. But besides that, the whole ballgame sucked.

So in a sense, they funded Avalanche Studios.

That was brilliant! That was the element that was absolutely fantastic. We’re still quite stunned, even today. They gave us an awful lot of money and we built a studio that I never would have dreamed of having. They didn’t know what to do with us, whether we were metal or what. It’s no great loss. Columbia is one of the most conservative major labels.

So it wasn’t such a bad experience.

No, it was quite useful. We just put it [the money] back into the band.

You’re kind of a rarity in that sense.

Absolutely. With rock groups, only about one in a hundred bands does what we do with their own money. To be honest, it’s really surprising that people haven’t got the clarity of vision. We always find it really strange that bands need a producer and all these people around to help achieve an end result.

It seems you guys are more grounded in reality, lyrically and elsewhere.

We’re not very positive about the whole [music] business, but we recognize exactly what we’re involved in, and that’s the thing. We’re very realistic, sometimes too realistic. Sometimes to the point where we get really depressed. Sometimes I think “why am I doing this?” We spend too much time over-analyzing the whole picture, and we’re constantly told “you should just get on with it” but we can’t help it. We’ve seen it so many times, sometimes we think, why bother? I love making music, that’s all I exist for, but the music business is so bureaucratic. It’s so based on bullshit that even when people want to hear your music, they don’t get to.

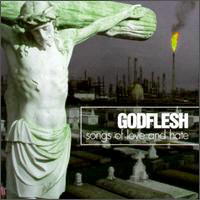

I have a question about the cover… Is that just one photo of the graveyard, and the factory in the background?

Yeah, most people assume it’s a computer collage. It’s a completely real photograph. Actually, it’s a place in the States called `Cancer Alley.’ A highly appropriate name for it because the factory is a petrol plant. Apparently, most people in the nearby town, a suburb of New Orleans, work at the plant, and consequently get cancer from the petrol and get buried right next to it. It’s so completely ironic, it’s incredible.

The visual fits the album.

Well, that’s the thing about this record, it’s very real. Very real horrors, very real fears, not comic book fantsies or horror or whatever’s fashionable.

Your music is more than rock ‘n’ roll, it transcends that. It’s based on need, I listen to it to deal with certain things.

That’s it for us. We use music in a very functional way. Essentially, we are a rock band, but rock in a very broad sense. We go deeper down.

I was flipping through Alternative Press and I saw an ad for Songs of Love and Hate saying `The new album from the godfathers of guitar-driven industrial music’. How do you feel about that?

Quite horrified really! (laugh) We tell people we dislike all this terminology, and they’ll turn around and say, ‘Well, how do you want to sell your records?’ We come up with a suggestion, and they’re so loose they don’t know. They can’t market it. When I read that a band is “industrial,” I think of Throbbing Gristle, not Godflesh. We’re essentially rock music. And godfathers! It belittles what we do, all this nonsense. I’m constantly at odds with the way we’re represented, but I think the problem is that we don’t know how to sell ourselves. If you’re going to use the term “industrial” in terms of Godflesh, at least use the term “rock” as well. You’d get somewhat closer to how we sound. We don’t really have anything in common with Nine Inch Nails or any of that stuff. At the end of the day, that’s why we’re not a huge band, but we’ve only got ourselves to blame.