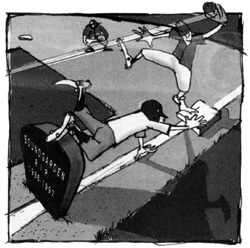

The Sporting Death of Soundgarden

The Sporting Death of Soundgarden

by Dave Liljengren

illustration by Timothy Walker

It wasn’t so much the fact that Soundgarden had broken up that bothered me, instead it was the source from which I heard the news that gave me the nudge. Without comment or apology, the amicable splitsville came up during the Mariners pregame show on a Seattle “Sportsradio” station.

I’m happily married to Seattle now, but I grew up in Chicago, and while I have nothing but contempt for the civic morass into which I was born, I do have fond memories of the Chicago Cubs and the generous number of their games which are broadcast, free, on WGN. As a child, I wasted hundreds of hours in front of the television, listening to a daft alcoholic and absorbing the pictures, descriptions and accounts of the star-crossed franchise with a devotion and intensity that I have invested in few, if any, endeavors since.

The daft sudsucker behind the microphone in those days was Jack Brickhouse, as Harry Caray was still covering White Sox games, which were televised only occasionally and only on Channel 44. Our snowy, hissing, tube TV, which hummed to life from a single point of light in the center of the screen and faded into blackness the same way, and which, through carbon dating, was estimated to have first roamed the earth in the mid-1950s, only went up to Channel 12. The ultra-high-frequency Sox were definitely out of the picture.

Unlike his modern-day Seattle counterparts, broadcaster Brickhouse, soused or no, would never have troubled himself to announce the passing of second-line heavy metal bands. Culture, popular or otherwise, was not welcome in the Wrigley press box. The friendly confines were just that: confined. To baseball. Or at least to whatever game the Cubs were playing.

I overstate slightly. Modern music did come up once during a rain delay when Brickhouse and his early-seventies cohort, Jim West, a particularly wooden, “just the stats, ma’am,” Cubs play-by-play announcer, were rummaging through drawers and pulling copy from the wastebaskets in an effort to keep the airwaves full of sportsgab, themselves employed, and the sponsors, the Tru-Link Fence Company and Danley’s Garage World, pleased with their spent advertising dollars.

In that era, the lovable, but usually faceless, “let’s play two and lose both” Cub players were moving distressingly toward individual limelight. When I say “distressingly” I am speaking from the viewpoint of the miserly Wrigley family, the gum-manufacturing owners of the franchise who preferred fielding a team of huggable, interchangeable, mediocre, “Cubbies,” all catching and throwing for the major league minimun, to fielding a team of high-maintenance, spotlight-seeking, winners.

By the early seventies, however, the Wrigleys could hold off the twentieth century no longer. The “Me-Decade” was upon them, along with the legacy of Curt Flood, the dissident player, anti-Cub, and seeming portent of baseball’s private apocalypse.

In the Cubs own dugout, their long-haired first baseman, Joe Pepitone, said to own his own restaurant, had been goaded several times by wacky sportscasters into furthering his ambitions as a singer by crooning, “My Kind of Town” on camera and in his Cubs uniform. Individualized publicity stunts such as this had previously been unheard of, and Pepitone was not alone in his instance of un-Cublike behavior.

Eventually, even the red-nosed Brickhouse got into the act, at least on a commentary level. It came up during a discussion of Carmen Fanzone, a triumphantly-named but inept utility infielder and journeyman trumpeter who was fighting to establish fame on both fronts. Fanzone was in Chicago, after all, and, at the time, brass rockers named for the city still lived on the charts. The rainy day music discussion unfolded thusly: after the mention of Fanzone, Brickhouse turned to West, who was thirty years younger – and, in Brickhouse’s bleary eyes, an apologist for the “youth of today” – saying, “While I prefer the Dukes of Dixieland, I like some of today’s beat. That’s what I like about it, in fact, the beat.”

The hissing sound which followed was the sound of the air leaving Brickhouse’s storied career as Cubs windbag. West did his best to change the subject, but the damage had been done. Brickhouse would be given a few more chances by WGN and the Cubs to right his career, but his cultural tin ear and inability to hide it made him a laughable anachronism by the time WGN brought in the swingin’, sixtyish, “Mayor of Rush Street,” Harry Caray, to shore up their image. But I think Brickhouse’s initial instincts were solid. He didn’t talk about anything other than baseball unless he absolutely had to, and in this he was correct. There should be a strict separation of sports and music. If we are to take Ken Burns’ teary dissertation on the subject with anything approaching the seriousness with which he thinks we should, then the national pastime needs space to live and die on its own. Though it can be comic at times, baseball is more than just another sitcom in search of ratings, and though baseball does much to sell cable to new viewers, it is more than an entertainment product whose value is judged by the number of units sold.

When Seattle’s “Gas” and “the Groz,” as sportscasters Mark Gastineau and Dave Grosby like to be called on their show, The Groz with Gas, brought up Soundgarden as a news item, they crossed a heretofore unencountered boundary of taste. Perhaps they didn’t know the consequences of their actions, but they served a disservice to both worlds by making the two collide.

I have no particular fondness for Soundgarden. In the confluence of punk and metal that became “grunge,” I have always numbered myself with the “punks,” (as silly as this may sound to those who’ve known me for a long time) even going so far as to shave my head at age 33 and strap my mid-life paunch and double chins into a leather jacket whenever I head out to hear music. The slow, snarling, notes of Soundgarden, however, clearly landed on the metal side of the above equation.

I have no overriding dislike for them either. Their success did bring acclaim to my town, and for that I am grateful. Their ouevre was broader than Twisted Sister’s and less grotesque than Ozzy Osbourne’s. For both of these I am grateful. Their name, deftly appropriated from a large, public, (and yes) heavy, metal sculpture that hums when the wind blows throught it, has to be one of the most serenely apt in rock history.

It is out of respect for both the passion of childhood to belong and the passions of adolescence to rebel, that I seek separate and unequal treatment for sports and music from the Groz and his everpresent friend, Gas. Baseball, with its odes to the boys of summer and the pennant races of autumn, deserves better than to be mixed in with every possible entertainment product. Similarly, heavy metal music, with its paeans to Satan and fiery stage shows, has gone to great lengths to distance itself from the simple, Middle American ideals embodied in baseball’s extensive mythology. The least we can do is offer both the respect they deserve, and keep each separate from the other.