The Doctor Has Left The Market

The Doctor Has Left The Market

The Death of William S. Burroughs and the Beat Generation

by William Ham

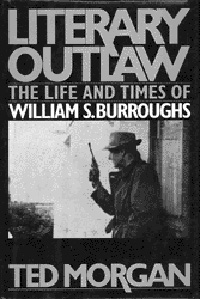

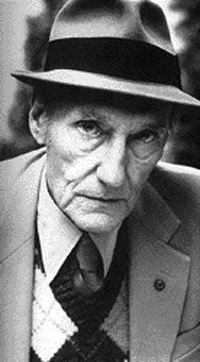

If, indeed, you can judge a society by its heroes, what does that mean to those of us who worshiped William S. Burroughs? Let’s see – a gay misanthropic misogynist, known for shooting both smack and his wife, with an unhealthy penchant for firearms, who wrote tons of books that many of us have paid lip service to but few of us have ever read past page ten, dies, and in certain circles it’s like a titan has departed. Not only is Burroughs’ passing, at an age (83) few would ever have expected he’d reach, the end of a bizarre and tragic life, but it’s truly the end of a strange, horrible and wonderful era – last call for the Beat Generation. Jack Kerouac went on the road to oblivion before most of us were born. Allen Ginsberg went out with less a howl than a whimper just a few months past. And now Dr. Benway has forged his last dilaudid prescription. The last pillar of intellectual rebellion has fallen, and I for one am standing beneath, dodging the remains and trying to figure out why this demise has moved me so.

The Beats, of course, represented a pivotal shift in American popular culture (which means American culture itself). As the post-WWII victory party gradually broke up and most of the revelers drifted off to languish in prosperity and birth the largest generation of ingrates in our history, the Beats were the ones left behind as the sun came up, poking at the trash on the floor and looking around for the next soirée. This was no ordinary group of thrill-seeking vagrants, however – these were smart, literate kids who caught a glimpse of the bottom of life, decided what they saw was beautiful, and dove in after it and kept coming back up to give anyone that would listen their reports. Which sounds pretty romantic until you get down there and realize just what it was they did see.

The Beats, of course, represented a pivotal shift in American popular culture (which means American culture itself). As the post-WWII victory party gradually broke up and most of the revelers drifted off to languish in prosperity and birth the largest generation of ingrates in our history, the Beats were the ones left behind as the sun came up, poking at the trash on the floor and looking around for the next soirée. This was no ordinary group of thrill-seeking vagrants, however – these were smart, literate kids who caught a glimpse of the bottom of life, decided what they saw was beautiful, and dove in after it and kept coming back up to give anyone that would listen their reports. Which sounds pretty romantic until you get down there and realize just what it was they did see.

Almost half a century later, it’s come abundantly clear what the Beats really were – the death throes of American literature. Part of that was timing: at around the time that Kerouac’s On the Road was finally published, Ginsberg did his legendary recitation of “Howl” at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, and Burroughs’Naked Lunch was crawling, junk-sick, towards completion, both rock ‘n’ roll and television were already infesting America. Television helped bring the Beats to national prominence (or Kerouac, at least – his burly, all-American good looks made for a far more acceptable public face of Beatdom than Allen’s maniacal Semitic features or Burroughs’ morticianly demeanor), though, as with everything else, the medium was quick to reduce it to caricature (Maynard G. Krebs, we hardly knew ye); rock ‘n’ roll, the art form of hopped-up teens, had as little to do with the Beats as they wanted from it. They swung to jazz, man – the cadences were real, they stank of the streets and the ghettoes, and besides, it sounded really great stoned. With TV and rock taking up the nation’s attention, there was less and less need for literature, much less a unified literary movement – after the Beats, there was none. (The closest we’ve come since is the whole Ellis/McInerney/Janowitz axis of the mid-eighties, a blessedly short-lived spasm of poor writing and opulent lifestyles – if it had caught on as the Beats had, the New York Times Review of Books‘d now come with a fashion supplement.) Their influences trickled down and took hold, all right, but lit was the least of their tributaries. Dylan was the first popular musician to put Beat to a beat; the free-form jazz stand-up of Lenny Bruce owed much to their methods of spontaneous composition; and popular TV shows like Route 66 reduced the peripatetic themes of On the Road to palatable, bite-sized weekly chunks. As for writing, it did inspire some notable practitioners (many of whom, like Norman Mailer, were already established), but too many of the people who had their minds blown by Beat picked up on the lifestyle more than the prose style. Since the media analysis focused on their outsized personalities rather than their artistic achievements (mostly because the media thought they hadn’t made any), tickets to authentic Beatdom rarely went beyond the platters they dug, the subterranean dives they frequented, and the drugs they took. The art was purely incidental.

Almost half a century later, it’s come abundantly clear what the Beats really were – the death throes of American literature. Part of that was timing: at around the time that Kerouac’s On the Road was finally published, Ginsberg did his legendary recitation of “Howl” at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, and Burroughs’Naked Lunch was crawling, junk-sick, towards completion, both rock ‘n’ roll and television were already infesting America. Television helped bring the Beats to national prominence (or Kerouac, at least – his burly, all-American good looks made for a far more acceptable public face of Beatdom than Allen’s maniacal Semitic features or Burroughs’ morticianly demeanor), though, as with everything else, the medium was quick to reduce it to caricature (Maynard G. Krebs, we hardly knew ye); rock ‘n’ roll, the art form of hopped-up teens, had as little to do with the Beats as they wanted from it. They swung to jazz, man – the cadences were real, they stank of the streets and the ghettoes, and besides, it sounded really great stoned. With TV and rock taking up the nation’s attention, there was less and less need for literature, much less a unified literary movement – after the Beats, there was none. (The closest we’ve come since is the whole Ellis/McInerney/Janowitz axis of the mid-eighties, a blessedly short-lived spasm of poor writing and opulent lifestyles – if it had caught on as the Beats had, the New York Times Review of Books‘d now come with a fashion supplement.) Their influences trickled down and took hold, all right, but lit was the least of their tributaries. Dylan was the first popular musician to put Beat to a beat; the free-form jazz stand-up of Lenny Bruce owed much to their methods of spontaneous composition; and popular TV shows like Route 66 reduced the peripatetic themes of On the Road to palatable, bite-sized weekly chunks. As for writing, it did inspire some notable practitioners (many of whom, like Norman Mailer, were already established), but too many of the people who had their minds blown by Beat picked up on the lifestyle more than the prose style. Since the media analysis focused on their outsized personalities rather than their artistic achievements (mostly because the media thought they hadn’t made any), tickets to authentic Beatdom rarely went beyond the platters they dug, the subterranean dives they frequented, and the drugs they took. The art was purely incidental.

Since I brought up drugs, allow me to use the subject to deconstruct the preceding generalization a bit and finally get around to the subject of this piece. The oft-stated point about the three big Beats is that, for a group of men who will be forever lumped together, they couldn’t have been more different in their creative approaches. Now, we could talk about upbringing, education, and the writers they themselves were inspired by, but I find it much more expedient to characterize them in terms of drugs. Kerouac, with his book-length run-on sentences and his method of recording every incident in his life no matter how paltry, was speed. (Near the end, when his prose became as bitter, bloated, and conservative as he himself was, he became booze.) Ginsberg, as his anger gave way to hippie communalism and cornball mysticism, was the bard of acid all the way. And Burroughs… well, I think most of us can suss that one out. The waking-nightmare visions, the nihilistic gallows humor and his obsessive reduction of his world view to a single metaphor of addiction and control (what he called “The Algebra of Need”) all point a loaded syringe at what he was all about. The smack-fiend’s viewpoint – desperate, unsentimental, and defiantly exclusionary – had never been so clearly and unapologetically delineated as in his first book,Junky (1951) (so much so, in fact, that Ace Books, the fly-by-night paperback house that published it, paired it up with the quickie memoirs of a narcotics agent to avoid looking too sympathetic). But Naked Lunch (1959), written during the most chaotic period of his life and cobbled together (mostly by Kerouac) from sheaves of disconnected pages written while trying to kick in Tangier, veered wildly from Junky‘s cold, documentary precision, actually capturing the addict’s paranoid, perversely erotic psyche on the page, a feverish cauldron of tar-black comedy, nightmarish hallucinations and swatches of autobiography that Burroughs would draw from for the rest of his days.

Since I brought up drugs, allow me to use the subject to deconstruct the preceding generalization a bit and finally get around to the subject of this piece. The oft-stated point about the three big Beats is that, for a group of men who will be forever lumped together, they couldn’t have been more different in their creative approaches. Now, we could talk about upbringing, education, and the writers they themselves were inspired by, but I find it much more expedient to characterize them in terms of drugs. Kerouac, with his book-length run-on sentences and his method of recording every incident in his life no matter how paltry, was speed. (Near the end, when his prose became as bitter, bloated, and conservative as he himself was, he became booze.) Ginsberg, as his anger gave way to hippie communalism and cornball mysticism, was the bard of acid all the way. And Burroughs… well, I think most of us can suss that one out. The waking-nightmare visions, the nihilistic gallows humor and his obsessive reduction of his world view to a single metaphor of addiction and control (what he called “The Algebra of Need”) all point a loaded syringe at what he was all about. The smack-fiend’s viewpoint – desperate, unsentimental, and defiantly exclusionary – had never been so clearly and unapologetically delineated as in his first book,Junky (1951) (so much so, in fact, that Ace Books, the fly-by-night paperback house that published it, paired it up with the quickie memoirs of a narcotics agent to avoid looking too sympathetic). But Naked Lunch (1959), written during the most chaotic period of his life and cobbled together (mostly by Kerouac) from sheaves of disconnected pages written while trying to kick in Tangier, veered wildly from Junky‘s cold, documentary precision, actually capturing the addict’s paranoid, perversely erotic psyche on the page, a feverish cauldron of tar-black comedy, nightmarish hallucinations and swatches of autobiography that Burroughs would draw from for the rest of his days.

To use a triple-entendre, he had caught the writing bug: words began to swarm from him like the hideous insects that permeated his writing, an unfettered stream that, as he put it quite bluntly, was viral in nature. Most writers grapple with the imprecision and mysterious, occult qualities of language with the passion of a tempestuous marriage; Burroughs, who pointed to the accidental murder of his wife as the moment he became a writer, actively distrusted it in ways that verged on the brutish. Even in his “straighter” work, he abjured style-manual syntax and narrative cohesion; when he introduced the cut-up method, rearranging his own and others’ texts to break the word and image locks of conventional language, his disrespect for the sanctity of the word was viewed with as much outrage in the fellowship of letters as his subject matter was to the bluenoses who attempted to ban his books in the early sixties. Even his admirers find his post-Lunch output problematic for that reason – his books constitute a vast, under-read corpus of intriguing techniques more interesting in concept than in execution (a literary John Cage, if you will).

To use a triple-entendre, he had caught the writing bug: words began to swarm from him like the hideous insects that permeated his writing, an unfettered stream that, as he put it quite bluntly, was viral in nature. Most writers grapple with the imprecision and mysterious, occult qualities of language with the passion of a tempestuous marriage; Burroughs, who pointed to the accidental murder of his wife as the moment he became a writer, actively distrusted it in ways that verged on the brutish. Even in his “straighter” work, he abjured style-manual syntax and narrative cohesion; when he introduced the cut-up method, rearranging his own and others’ texts to break the word and image locks of conventional language, his disrespect for the sanctity of the word was viewed with as much outrage in the fellowship of letters as his subject matter was to the bluenoses who attempted to ban his books in the early sixties. Even his admirers find his post-Lunch output problematic for that reason – his books constitute a vast, under-read corpus of intriguing techniques more interesting in concept than in execution (a literary John Cage, if you will).

All of which sounds rather unappetizing to the uninitiated, I admit. Yet Burroughs went from being the creaky third wheel of the Beat juggernaut, respected for his genuine outlaw status and his near-martyrdom on the altar of censorship but creepier and less inviting than the gregarious, life-embracing Kerouac and Ginsberg, to overshadowing them all in stature and in influence. What, precisely, did Burroughs have that made him more than a mere cult figure to a small band of debauched academics? In the little space I have left, allow me to list off a few reasons:

He had The Voice. It’s been said that the Beats’ writing makes more sense once you hear it read aloud, and that’s truest of all when it comes to Burroughs. He was as much a performer as he was a writer – many of his best stories began as routines told to entertain his friends, and listen to one of his many spoken-word recordings and you can’t help but be taken by his bone-dry, Midwestern drawl, as distinctive as W.C. Fields under heavy sedation. Even the cut-ups gain an incantatory power when run through that slow, creaky voice, and his more straightforward narratives take on the character of outrageous shaggy-dog stories as told by a deadpan stand-up comedian/snake-oil salesman.

He had The Voice. It’s been said that the Beats’ writing makes more sense once you hear it read aloud, and that’s truest of all when it comes to Burroughs. He was as much a performer as he was a writer – many of his best stories began as routines told to entertain his friends, and listen to one of his many spoken-word recordings and you can’t help but be taken by his bone-dry, Midwestern drawl, as distinctive as W.C. Fields under heavy sedation. Even the cut-ups gain an incantatory power when run through that slow, creaky voice, and his more straightforward narratives take on the character of outrageous shaggy-dog stories as told by a deadpan stand-up comedian/snake-oil salesman.

He was funny. Kerouac called him “the greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift,” but that’s faint praise – his talent for bloody, scatological exaggeration (see the operating room sequence in “Twilight’s Last Gleamings”) and dead-on social observation (“Thou shalt not blow pot smoke into the face of thy pet”) made Swift look like Dave Barry.

He was a prophet. With chilling prescience, he foresaw everything from AIDS to the popularity of autoerotic asphyxiation, and the aspects of his world view that seemed delusional in the fifties and sixties (particularly the sense that the world is controlled by sinister, unseen forces) are practically gospel to a large percentage of the populace today.

He was accommodating but impervious. In the last fifteen years of his life, he was utilized whenever a musician needed a hip voice for a record, a publisher needed a pithy jacket quote, and a director needed somebody to play a junkie priest opposite Matt Dillon. Yet even when his Beat-spokesman-for-hire status took a bizarre turn (lest we forget, he did a Nike ad), his voice rang out loud, clear, and uncompromised.

He did his work and went. His professed goal was to cast out the demons (personal and otherwise) that compelled him to write, to “rub out the word,” in his friend Brion Gysin’s phrase. A complete inner silence was his idea of true happiness and peace. It seemed to have worked: he stopped writing novels in his last decade and wrote mainly in his journal. And it’s the last entry in that journal, written the day before his death, that suggests that the old misanthrope had finally found what he was looking for, simply and movingly closing the book on both his troubled journey and, by extension, the whole rootless quest of the Beat Generation:

“Love? What is it? Most natural painkiller. What there is. LOVE.”