Two

Two

Voyeurs (Nothing)

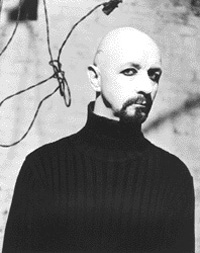

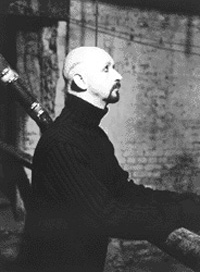

An interview with Rob Halford

by Scott Hefflon

You haven’t been through Boston in quite some time.

I remember I was on a quest for some authentic Boston creme pie. I schlepped to this big supermarket that seemed to be miles and miles away, but I eventually got a couple of pies on the bus and everyone devoured them.

Was it fulfilling?

Of course it was. I’d accomplished a Boston creme pie in Boston. We also enjoyed all the goodies that they cook outside (on Lansdowne Street behind Fenway Park when there’s a Red Sox game), and the next day I saw a game. It was a great visit.

You’re in New York, right?

Yes, I’m in the brand-new Interscope building. There’re workers walking around, installing phones and carpeting. Jimmy Iovine, the president, was wandering around trying to figure out where everyone would be sitting. It’s a beautiful building with a great view over Central Park.

Your last band, Fight, released two albums. When did the second come out, and when did you realize you wanted to leave the band?

Well, the first album was War of Words and the second was A Small Deadly Space. I can’t remember the exact year, but I know I started working on Two a little over two years back.

Was your heart still in recording and touring with Fight?

Not a full heart, because I was still searching for the right environment, the right people to work with. Two was one of those situations in the music business where somebody makes a phone call and introduces you to somebody else, and that gets the ball rolling in a different direction. It was after a few dates supporting A Small Deadly Space that someone told me about a guitar player named John Lowery. John and I spoke on the phone, and we hit it off first on the personality level, which is important in any musical environment, but after we’d spent a little time in each other’s company, we wondered what it would be like to make music together. He was working with Bob Marlette, a producer and songwriter from Los Angeles, so the three of us started sitting down in Bob’s house with a couple of old acoustic guitars, and basically experimented, had fun, and wrote music that pleased us. We’d never set a format or plan, we just made a song, enjoyed it, then moved on to something else. Within a short space of time, we had a pretty substantial body of work that we felt really good about, so much so that I wanted to go into full demo and pre-production mode. At that time, I spoke to JJ and Brian, the two final members of Fight, and told them what was going on. They understood, and we decided that we’d had a couple of great records and some shows, but we were going to go off and do our own things.

Did they get that Fight was pretty much over anyway? [Note I didn’t say “the Fight was pretty much out of you.”]

Did they get that Fight was pretty much over anyway? [Note I didn’t say “the Fight was pretty much out of you.”]

I don’t think so. I think it was a big surprise to everyone, myself included. I don’t recall being open with them and saying, “Look, I’m just not happy musically.” Because I was happy, I felt content, but I always felt I’d only scratched the surface of this journey I wanted to make. In all honesty, maybe I didn’t really understand the significance of what Fight was about and what it was achieving. If we had stuck together, more things would’ve happened. As it turns out, this came along and it seemed the natural way to go. What I was doing was completely stepping away from my heavy, heavy past. This connection with Lowery and Marlette was on a whole different musical level.

Coming from an increasingly heavy background – Painkiller being the heaviest Judas Priest album, and two Fight records taking it even further – what were some of the places you wanted to go on this journey?

Each song became its own significant moment. When you refer to the music as a complete piece, it’s very cohesive. But when you pull the songs off of it, one by one, there’s no real defining moment. The music we were writing was like hopscotching along from place to place. Each one was so complete and strong in its musical statement, there was no specific time when we felt we’d achieved our destination.

So it’s more you approached Two with an un-goal: you didn’t want to play heavy metal.

That’s fair to say. That’s what drew me to Lowery and Marlette, knowing I wasn’t going to be doing anything super-heavy.

When you know what you don’t want to do, there are infinite options…

Absolutely. This was the first time I’d gotten that feeling in such a long while.

Not to discredit large chunks of your career, but it’s great to hear you sing melodies the rest of us can kinda sing along to.

Thank you. That’s a compliment I really appreciate. If Two makes that connection, we achieved the only goal we’ve set out for – to make simple music people can enjoy and relate to.

The bio quotes you as feeling a certain obligation to fans’ expectation for you to show off your range, belt it out, and dazzle them.

It’s a difficult situation. When people support you, obviously you’re grateful for that support, but you have to be very careful that you don’t let it take control. Artistically and creatively, you have to be true to yourself. You can’t write this song or sing that note for someone else’s expectation. When you start behaving in that way, your music becomes a product.

How did this vocal style change occur?

How did this vocal style change occur?

My vocal techniques were completely different on this record. Admittedly, over the years, some of the Priest work was a little sedate and laid-back, but this record was extraordinary for me, as Marlette coached and directed me into a new way of singing. He taught me to approach the songs in a non-metal way. I think of the adage that you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. He was able to reinforce my belief that you can never stop learning, that there’s always something new and different to try.

How did you hook up with your producer, Bob Marlette?

He didn’t really know much of my past. I brought him a few of my CDs, and he said, “Humph! You aren’t going to be singing like that on this record.” He taught me to sing in a more pure, intimate way, instead of belting it out, hoping to get the notes right. With Bob, he helped me dig deep, deep inside me, to the roots, from the soul, and express myself in a very personal way.

What’s Bob’s background?

I don’t really have the full item on him. He’s been a musician all his life, a very accomplished keyboard and guitar player…

But what has he done that makes you consider his opinion valid? To take your career in a new direction, you must have really trusted him.

If you met Bob, within 20 minutes you’d consider him a lifelong friend. From the moment we met, I felt I should listen to what he suggested I try. I’m a musician who’s able to do that. As long as my gut tells me it’s right, I’ll give a new idea some time and see what happens.

And how did you hook up with guitarist John Lowery?

I was at Concrete’s Foundations Forum a few years back, being presented a lifetime achievement award, and a journalist friend of mine and I were talking, and John’s name came up. I wasn’t aware of him or his work. He’s in his twenties, a skinny, blond-haired guitar geek, but a really nice guy. He’s a virtuoso, to say the least, a fully accomplished performer. But he was searching for his own identity in a band. He’s worked with k.d. lang, Ozzy Osbourne, Janet Jackson, he’s worked on music scores for television and major films – he’s done everything. He’s much like me in his capacity to appreciate all kinds of music, but he’s found his moment in Two, the band he’d like to be known for.

Is Two, in essence, named because there’re two of you?

Originally, yes, as simple as that sounds. But the more we thought about it, it seemed even more appropriate. Action creating reaction. The balance of positive and negative, good and bad. The relationship between two people. A great number of harmonic, and sometimes discordant, situations come of two people. It began to take on more substantial meaning. And then we took the letter T and flipped it over into the number 2, and that was more based on technology, numerics, and binary language. We didn’t want a band name that created a mental picture, more a symbolic identification.

What was Trent’s influence, and how did you meet him?

I met him at Mardi Gras about two years ago when some friends pointed out where his studio was. Dave Ogilvie took me on a tour of the place, and that was the first time I’d met “Rave.” A while later, Trent showed up. We talked about what we were doing and where we were going, and he asked if I’d leave demos of the songs so he could listen to them in his own time. And that was it. A number of weeks or months later, he called and offered me a deal with Nothing Records, which was just mind-blowing, and said he’d like to be involved in taking the music to the next level. I didn’t really understand what he was trying to do, but after a few days in New Orleans, I got a grasp of his blueprint ideas for the music. I took off to Vancouver with Rave Ogilvie, and began the whole reconstruction process of taking the original songs, tearing them apart, and putting them back together in a new shape.

It may be a hard thing to put in words, but how did Reznor’s touch affect the music?

By percentage characteristics, I’d have to say he improved it 80% or more. The basic structures of the songs were very simple in their format. Two was basically a modern, guitar-driven rock band. Reznor’s involvement brought in all these various other musical aspects, so there’s a vast difference between the original sound and direction, to the one that ended up on the album. Very different production, engineering, mixing techniques, as well as rewriting the material. The melodies haven’t changed much, but everything around them was turned around. Without Reznor, we would’ve had a good rock record, but with him, I think we have a substantial situation. When we were figuring out the credits, he wanted to be executive producer. He was very drawn to the music and so involved in shaping it, that’s the proper title for him. It was Trent’s musical vision, background, and expertise combined with the raw material that we brought in that made Two complete.