Gang of Four

Gang of Four

Return the Gift (V2)

An interview with vocalist Jon King

by Martin Popoff

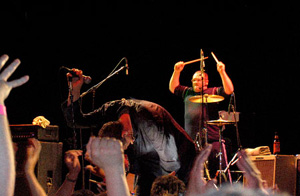

UK rhythm chopists Gang of Four are out touring to great critical acclaim, bringing with them their hard-to-love hits from the early ’80s, full-flush reunion lineup in place, namely Jon King on vocals, Andy Gill on guitars, Dave Allen on bass, and Hugo Burnham on drums. Read carefully Jon’s comments about the band excelling live – this is no idle boast; the stage sound is excellent, the beats that are often thin and gnat-swatting on record transforming to busty and bountiful in the flesh. In other words, the spaces, or “drop-outs” that on the albums made for a sort of grim and erratic art rock work to great advantage on the stage, where a little contemplative, head-sorting space is always welcome. Anyway, here’s Jon, forced (by me) to celebrate the legacy, resulting in a whole lot of context in which to evaluate this solid gold asterisk of an act, rejuvenated and reminding.

Where are you in the cycle for a new studio out album?

The thing we’ve been working on is a re-recording of our favorite things from the first couple of albums. We set about trying to create versions of our favorite tunes which were different and exciting and reflected more what we sounded like live. I think Gang Of Four as a band – the most authoritative version of us – is when we do a live performance. But live albums tend to be disappointing because of noise and lack of control, so we tried to do something that captured that feeling, that excitement. And from that, we thought it would be good to play with these sort of artifacts. And so we handed over a double CD. One CD will be re-recordings of our favorite tunes, primarily from the first two albums, but a couple from later ones like “Uniform” and “We Live as We Dream,” and then we handed over the backing tracks to people like The Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Gwen Stefani and Dandy Warhols, Massive Attack, Futureheads, and they’ve all sort of done, I wouldn’t say wacky versions, but they’ve taken the backing tracks and they’ve done their own thing. So we just tried to have an artistic new take on the old stuff.

What elements went into the band’s sort of choppy, astringent, jerky sound?

What elements went into the band’s sort of choppy, astringent, jerky sound?

When we all set out on the project, we had four individuals who contributed into the pool of ideas. We had a really heavy, solid rhythm section, and this kind of fractured, busted-up guitar, and this unusual lyrical approach. Those things were melded together. But it’s hard to draw any particular bit out of it. But the ideas were around deconstruction, so that you would hand over leadership from one part of a song to another; the idea of drop-outs. We don’t play any reggae music, but some of the ideas, the inspiration came a lot from dub reggae and funk. That sort of idea that you hand over leadership, or you drop out of the songs, as you go through is really a central part of it. Live, we move from one mic to another, sometimes balance two things happening at the same time. Sometimes, the lyrical things are commentary on another bit. I think one of the songs that’s most theatrically effective live is “He’d Send in the Army,” where I play a microwave with a baseball bat. Yeah, I hit this thing on the downbeat of the four, and then Andy improvises a guitar part around this initially quite simple thing. And then this very heavy rhythm section comes in, and then it’s drop in, drop out, and the vocals come and come out. And I guess it’s trying to have this sort of sense that you can change the music as you move along. One of the things that’s happened over the last couple of weeks on our U.S. tour, is that people are drawing the analogy between us and John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman. And we’re not a jazz band, but I understand where that comes from, the idea that you’re trying to get maximum tension from something which is preordained, in the moment itself.

Were you coming in with a punk ethic? Were you playing at the top of your ability, or were you virtuosos underneath this sparse, almost awkward approach?

We were never a punk band. I think the closest band at that time to us was Talking Heads, and they were peers of ours. When we played in New York, somebody shouted out from the audience, “David Byrne’s taking notes!” And he was; he was writing stuff down. The way that we approach it was to do something different. The punk ethic was very much “anyone can be in a band” and “you only need to know three chords to be in a band.”

So how good were you guys?

Well, all good musicians. In 1976, we went to New York and stayed with a friend of ours in St. Mark’s Place, and we used to go to CBGB’s every night, and our friend, Mary Harron, who many years later became the director of American Psycho and I Shot Andy Warhol, she was going out with Jay Dee Daugherty, who was Patti Smith’s drummer, so we ended up hanging out in ’76, with Television and Richard Hell & The Voidoids and Patti Smith Group. So I think we were closer to Television than anything that happened in the UK. In fact, all of the bands I like are American acts anyway. When I say American, I mean North American, which includes Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, the greatest Canadian musicians ever. Actually, David Allen used to rent Joni Mitchell’s house for 12 years, so he knows Joni very well. So it was more from those ideas about culture and art, which is, I guess, more of a New York thing than a London thing. The London thing was very conservative, musically. The Sex Pistols, if you take John Lydon’s individual brilliance as a person and the lyrics out of it, it’s really boring music. It could be Black Sabbath on a bad day. Never Mind the Bollocks is a very conservative record. So setting against that, you put Never Mind the Bollocks on one hand, against a song like “Anthrax”: feedback, twin vocals, rhythmic groove, they’re universes apart.

Who influenced you guys, Magazine, Wire…

We lived in Leeds, and in North American terms, it surprises people, but Leeds is only 30 miles away from Manchester. And it seemed like a huge distance. We were very good friends with The Buzzcocks. In fact, The Buzzcocks, who wrote brilliant punk songs, were very generous. Pete Shelley and their manager, Richard Boon, who’s still a mate of mine, were really generous. They used to let us play with them. And we then had an office with The Slits and The Pop Group. So there’s the Gang Of Four/Slits/Pop Group office, and we played quite a lot with those guys, and The Slits were an absolutely brilliant band. Their first record was was sort of reggae-tinged, but avant-garde in a strange kind of way. It’s really worth listening to. At that time, we weren’t like the Magazine acts. I think there was some parallel with us and Wire, but I didn’t listen to them much, and I’m sure they didn’t listen to us much. They were much more art rock, but I admire what they were setting out to do. But again, it was probably closer to Talking Heads, although I think they were closer to us. Because we started this thing, this fractured, loud, arrhythmic guitar, astringent guitar, with kind of funk grooves, not actually funk in the way that P-Funk would be funk, but it has that sort of driving danceability to it.

How were you perceived in the UK at your apex, sort of ’82, ’83? Were you commercially successful? Did the music papers like you? Did people understand you?

We were darlings of the NME and Melody Maker at that time, so we were always in the front pages of those magazines. We were very much a musician’s band. You can draw the parallel with Velvet Underground, this idea that Velvet Underground never sold that many records, but everyone who bought their record set up a band. And I think it was kind of like that with us. We played pretty big shows in London. But in the UK, there’s a lot of dislike of local heroes; there’s not much celebration of them. So we were more popular in Manchester than we were in Leeds, even though we came from Leeds. And in London, we did great. But it was mainly the U.S. that we did well.

Any strange pockets around the world where you did exceptionally well?

Yugoslavia, strangely. We were really big in Yugoslavia, when it was under Tito. And I don’t know why. We played these big sort of sports halls, stadium-type places. Portugal we were really big in, for some inexplicable reason. Although we were banned from going to Portugal once when the Pope was making a visit, because they thought we’d cause trouble. I don’t know why; we never did. But we had two records banned in the UK. “I Love A Man In Uniform” when it was in the Top 30 was banned because the Falklands war had broken out. Actually, the narrative of the song has nothing whatever to do with the Falklands War. I would have had to have been clairvoyant to know this obscure war in the South Atlantic was going to break out six months in advance of it actually happening. I could’ve gotten a job in British intelligence. But that was banned, and “At Home He’s A Tourist” was also banned in the UK. So both times we had charted singles, that was in the teeth of it, not being allowed to be played on the radio.

How about a quick rundown of the studio albums, favorites, least favorites?

I like the first two albums very much. In fact, 90% of what we play tonight is from those two albums. And a song like “Army” was like climbing a mountain. We set out certain types of rules. I’d write my lyrics so they didn’t actually have rhymes in them, and there are words I wouldn’t use. And we would try to avoid things like key changes, or chord progressions. I mean, a song like “To Hell With Poverty,” which, I think is an absolute standout, rocking, loud song, actually doesn’t have any chords in it at all. It’s only got three notes, not played at the same time. I would just say to Andy, “A chord is any three notes played at the same time.” Because you couldn’t quite work out what they were. “To Hell With Poverty” has only got three notes in it, but it’s an incredibly relentless, driving, loud sort of monster, rockist kind of thing. My least favourite record was the Hard album. We were trying to do something that was very ambitious and it didn’t come off the way we wanted it to. I suppose the closest thing to it is what Scritti Politti did; they were mates of ours, when they did the Cupid & Psyche 85 album, which was to make a fractured take on disco. And we even decided to put a color photo that made us look like a disco-y kind of band. It was not really very successful for a variety of reasons.

How about the female vocal experiment with Sara Lee, was that successful?

How about the female vocal experiment with Sara Lee, was that successful?

Again, we were just trying to push the envelope. I mean, “Uniform” I’d seen as a kind of pop infection: It even has a verse, a bridge and chorus. It’s probably the closest we came to writing a conventional song, but even that was banned. So we certainly were seen by producers and programmers as being a dangerous proposition. Because the whole point of the band was to challenge the type of conversations you could have in music. And the conversations happening in rock music were very narrow. I mean, Bryan Adams, to pick on another Canadian act, alongside my two favorites Neil and Joni, he has a very limited subject matter lyrically: Cars and birds and nostalgia for when you were in high school. Which characterizes a lot of AOR. And so the idea was lyrically to create a new set of subjects, stories about the commodification of daily life, or the struggles of finding something useful for yourself. Like the lyric to “Return The Gift” is, you know, you see these commercials, you get a whole set of Tupperware bowls, and if you take them for ten days, you get a gift, yours to keep, in any case. And of course, you have to send the gift pack, because if you don’t, of course, you’re drawn into this thing. And so, finding these little vehicles, like the lyrics to “At Home He’s A Tourist.” I think the Talking Heads’ take on that song was “You may find yourself in a…” I think that was David Byrne’s classy take on “At Home He’s A Tourist.”

Have you ever seen anything in the press where the Manic Street Preachers have cited you guys as an influence?

I don’t know. We were not really a political band in the way that the Manics are. The Manics make very polemical, political statements, like Billy Bragg used to do in the UK. “The powers that be will try to stop you voting.” Or some statement of that kind. And that was never an area I wanted to get involved in from a writing perspective. I think that’s why Gang Of Four is now name-checked by most of the hip guitar-oriented new bands. Because the lyrics weren’t about current affairs. I never wrote lyrics about current affairs, but they still had relevance. So “To Hell With Poverty,” the lines “Some are insane/they’re in charge” still applies. We didn’t say Margaret Thatcher’s a fascist or anything like that, which would’ve been a Manic Street Preachers thing. The Manics have that heart on their sleeve thing, which is obviously good for what they do. “Richard Nixon” I thought was kind of a cheap shot. Don’t do a song about a dead president, do it about a live one.

Musically, on an album of theirs like The Holy Bible, you can see your influence. Another place is that little bubble that made INXS and The Fixx famous…

Andy was big mates with Michael Hutchence, and he produced Michael’s only solo thing. Michael Hutchence was a devoted fan. He knew every single, In fact, I think he knew our music better than we did. Like these days, if we can’t work out the chords to one of our old songs, Andy phones up the guy in The Futureheads and he’ll work it out, because he knows the chord structures better than we do. I think the Chili Peppers were the closest, and they were devoted fans of ours. In fact, on the 100 Flowers Blooms box set, there’s a picture of Flea jumping on stage, in L.A. This naked man jumped out of the audience and grabbed me in the middle of a song. It was hilarious. This was 1982 or something, and they were just starting out. It turned out to be Flea. And then Andy produced the first Chili Peppers album. (laughs)

(www.gangoffour.us)