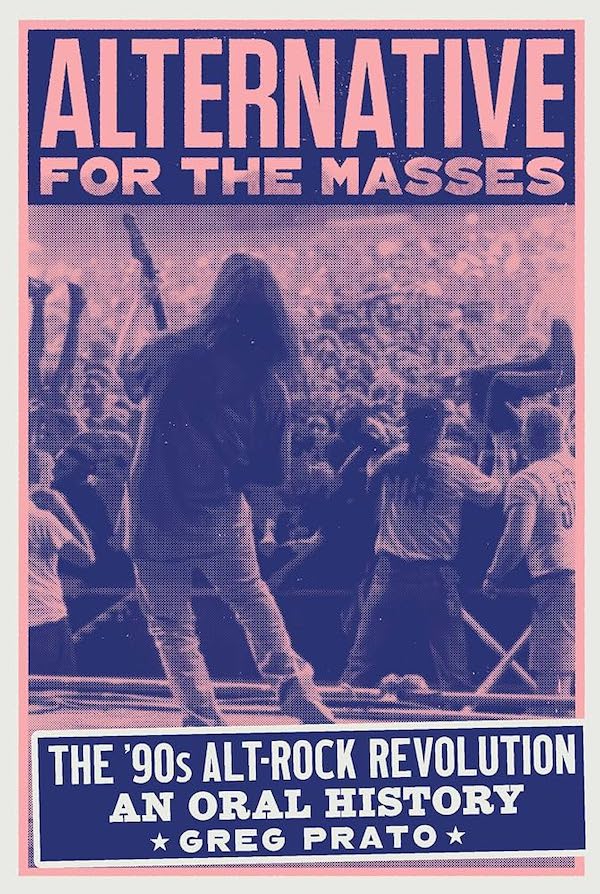

Alternative for the Masses: The ’90s Alt-Rock Revolution – An Oral History

Alternative for the Masses: The ’90s Alt-Rock Revolution – An Oral History

Written by Greg Prato (Motorbooks/Quarto)

by Scott Deckman

Greg Prato has written quite a few books. I’m a sucker for oral histories, the touchstone being Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk. While nothing I’ve read tops that tour de force, Alternative for the Masses: The ’90s Alt-Rock Revolution – An Oral History is good. Especially if you were there, which I was. Prato laces his epoch-defining conversations with quick little asides written by participating actors, relaying poignant moments from the time. They add color to the era, as do the many pictures throughout. Prato’s introduction sets everything up, and the playmakers tell the tale of alt-rock, from its punk and college radio beginnings, to Nirvana’s seminal sophomore record, Nevermind, which, 34 years later, has not been topped for cultural impact, to the long afterward, which was great for a while in the mainstream, but soon crashed out as retreads took over the airwaves.

We hear from artists involved in the underground/college rock scene and the later alternative rock explosion it led to, though first-wave punks and proto-punks aren’t represented (while strictly not necessary, it would have been nice). Prato interviews quite a few musicians, including Lou Barlow of Dinosaur Jr./Sebadoh/Folk Implosion, Evan Dando of the Lemonheads, Bob Mould of Hüsker Dü and Sugar, Eddie “King” Roeser of Urge Overkill, Moby, Mike Watt of the Minutemen/various projects, Al Jourgensen of Ministry, Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi, Page Hamilton of Helmet, Paul Leary of the Butthole Surfers, Robert DeLeo of the Stone Temple Pilots, Les Claypool of Primus, Art Alexakis of Everclear, and King Alt-Rock himself, Frank Black of the Pixies/Grand Duchy/solo artist. We hear a little from Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo, but not from the rest of the band, nothing from Gordon Gano of the Violent Femmes, the Green Day guys, Henry Rollins, Beck, members of R.E.M., or anyone from the Ramones (yes, most of the bruddahs have been dead more than 20 years). The voice of Kurt Cobain, the leader of the mainstream alternative rock movement, is not in these pages, either (I know, he’s been gone for 31 years), and the take of Jane’s Addiction’s Perry Farrell, who can be called the era’s godfather, is missing as well. There is also no Pearl Jam, Alice In Chains, or Soundgarden voices (Prato covered this ground in Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music). Not everyone will talk, that’s how it is, but the people we do hear from tell the tale of the ’90s well.

There are chapters on the genre’s singers, guitar sound, and rhythm sections, and how they differed from previous eras, particularly wanky hair metal. In alt-rock, it was the song over technique. There is a chapter on the post-Nevermind boom, where majors were looking for the next Nirvana or Pearl Jam, signing anything similar or even somewhat adjacent they thought might sell. This also led to a major label/indie label divide when small-scale bands jumped at the chance to have an actual recording budget and bus to tour in. Punk rock ethics held sway for some, but not others. These days, people are bigger whores than ever, and many have no ethics. One chapter is devoted to era catchphrases and buzzwords (alternative — see book title, college rock, indie rock, Generation X, and slacker), another to how the word was spread in the ’90s other than through MTV (7-inch singles, live shows, stickers, TV appearances, record stores, soundtracks, tribute albums), and a third to musical subgenres.

The importance of MTV and their programming post-Nevermind is discussed. Pre-internet, the channel was a tastemaker, and the sudden switch from hair bands and pop to grunge was fairly swift and striking. The suits knew what was happening and how to exploit it. In fact, MTV was as big a boon to alt-rock as it ever was to hair metal, ’80s new wave, pop, or rap. From what I can remember of the early ’90s to about 1997, back when the channel actually aired videos, alt-rock bands were played all the time, with shows like 120 Minutes and Alternative Nation specializing in the genre. Video really did kill the radio star, at least for a while, and bands getting $200,000-400,000 budgets for a single video during the genre’s peak proves how many units alt-rock could move back in the day.

The recollections of former MTV VJ, now Fox News contributor, Kennedy, who was a doyenne of the movement, are featured throughout. Though she was typecast as wild and crazy, she was always right of center. A highlight, or lowlight, of the book is the story of the VJ’s virginity surviving a close call with the married Johnny Rzeznik of the Goo Goo Dolls. Matt Pinfield, influential host of 120 Minutes, gives his story, too. Pinfield gave gravitas to the movement, someone at MTV who really knew what he was talking about.

Lollapalooza, a tremor before the coming storm, is covered, both on its own and in conjunction with an early chapter on Jane’s Addiction. British counterparts, multiday single-site Reading Festival and Glastonbury Festival, are discussed too (so is Pinkpop Festival in the Netherlands), as are both sides of the pond’s press. Spin was alt-rock’s American home, but had to compete with Rolling Stone, who covered the scene as well, as did CMJ (the company published two separate magazines; the owners also facilitated a yearly, multiday festival from 1980-2015). The big boys also had to fend off upstarts like Alternative Press, whose former longtime editor in chief Jason Pettigrew is interviewed, showing us just how hard it was for smaller pubs battling corporate giants for coverage and all-important magazine covers. Britain trades NME, Melody Maker, and Sounds get discussed, as does radio, briefly. It’s profound when you think that radio and magazines were the only way to find out about music and scenes before the internet, other than going to shows, but how many gigs could you go to? Kids today have it easy (free music, free info, bands’ social media, YouTube, blah, blah), but also kinda hard (there’s just too much music today, making discernment tough).

Grrrl power gets a chapter, when rock became more than just a boys’ club. While we don’t hear from important voices like Liz Phair, Kim Deal, Tori Amos, Björk, or Polly Jean Harvey (we read about them, though), we do hear from, among others, Lori Barbero of Babes in Toyland, Johnette Napolitano of Concrete Blonde, Miki Berenyi of Lush, Mary Timony of Helium, Tanya Donelly of Throwing Muses/Breeders/Belly, and Tracy Bonham. These women’s conversations are peppered throughout the book. Curiously, all-female package tour Lilith Fair only gets a brief mention and isn’t discussed.

The section on alt-rock producers focuses on who you think it would: Steve Albini and Butch Vig. Producer and mixer extraordinaire Andy Wallace is discussed quite a bit, but era producer Brendan O’Brien is hardly mentioned at all; neither are heard from. Gil Norton, Dave Jerden, and Terry Date would have been good interviews as well. We do learn about others, though.

The day the music died for my generation and its aftermath is covered, of course. Saying nothing of Kurt’s official death narrative, his passing was personal for some and left a chill on the industry. Drugs, especially heroin, have a chapter, and it’s true we’ve lost quite a few to substance abuse, and it’s more than a cliché that drugs and alcohol have ruined many an artist’s life. The scene survived Kurt’s death pretty well — for a while. The truth is, commercial alt-rock was good until the end of 1996 or 1997ish, but after the punk revival, things started spinning down, and if you followed the big stations, you got watered-down grunge, nü-metal crap, and who knows what else.

One funny thing is Prato listing the Reverend Horton Heat leader Jim Heath as the Reverend Horton Heat in the discussion. Cult bands turn up on these pages: David Pajo of Slint is heard from, and his band gets some mentions, Jimmy Flemion of the Frogs tells his tale, and the voice of Cris Kirkwood of the Meat Puppets is prevalent. We also hear from Roger Joseph Manning Jr. of Jellyfish, a band which a friend of mine adored, but I thought was mid (his next project Imperial Drag’s eponymous debut is one of my favorite records, though).

There are also good sections on era headliners, influential bands, and top records and songs, the latter two of which have the artists themselves (mostly) commenting on their creations. In the end, these are enjoyable and informative conversations from those who helped make the ’90s my favorite musical decade. Recommended.

Links:

Linktree

Motorbooks/Quarto

![]()