Orbital

Orbital

InSides (FFRR)

An interview with Phil Hartnoll

by Joshua Brown

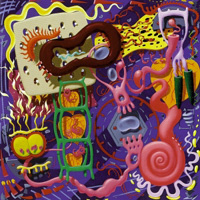

The cover art for InSides, the new Orbital album out on Internal in Britain (and in America on Full Frequency Range Recordings), represents imaginary bodily organs given voice and characterization. The cover art, album title, and label name suggest an inward direction for the music composed by brothers Phil and Paul Hartnoll. This is in contrast to Orbital’s last full-length, 1994’s Snivilization (ffrr), which was a look through divine eyes at all of our exteriors, if you will. A God’s Eye view of society through virtual reality sunglasses. They asked the question “Are We Here?”, and were answered by another question: “What does God say?” Orbital hailed in the rave explosion of the early ’90s with “Chime” and “Belfast” (from the “green album” (ffrr)). Looking back on a year or so of raving madness and general fun, peering into the future and sorting out meaning from it, Orbital gave us the “brown album” with singles “Lush” and “Impact” (and the impact it made was rather lush). InSides, with its interior focus, greets you like a Zen master with greasy fingernails. Industrial grade music without industrial grade baggage.

Orbital are generally plugged as the group that proves electronic music can be live music.

There are no tapes or anything running. So what we’re essentially doing is setting up our studio on stage and running it all from sequencers, so we can improvise with the structure.

Can you elaborate?

Basically, we’ve got three sequencers with eight buttons each. Everything within that track is separated on the individual buttons. You can, for example, bring in the bass line whenever you want, or you can bring in the hi hats. Anything within the structure of that song. So the way we choose to arrange the track is entirely down to the night. It gives you more scope. If the audience is a bit mellow, for instance, you tend to pick up the vibe and try to work them up a bit crazier.

Rather the opposite of what many people think of your type of music. They stereotype it as totally “mechanical.”

When we’re playing live, it’s actually more improvised than a traditional band. Traditional bands are stuck with lyrics, and have to follow the verse-chorus-verse format, things like that. We don’t follow those rules at all, but we do follow a pattern. If we play “Impact,” for instance, it will be quite similar to the arrangement which we recorded, but it changes. It’s more basic, rougher around the edges. Rawer, like live music should be, in my opinion. Because we don’t use tapes, we’re not restricted to a particular length track.

What did you and Paul grow up listening to?

We’re into lots of different types of music. Growing up, we liked the same stuff. Paul was playing guitar in a school band sort of thing when he was 15.

During the punk era?

Yeah. Second generation punk though. Like Crass. Paul was into more American punk, like Jello Biafra and Dead Kennedys. I was into the first generation, the more British thing. The attitude was there and all… but I don’t know, I guess I was a bit silly.

I’m not sure which punk generation I prefer. I’d say they’re about equal.

Certainly the issues that Dead Kennedys dealt with were a lot more political. Much more true, I’d say, than something like the Sex Pistols, which was just a con, really.

It’s interesting to see what’s happened to those performers since then. John Lydon does P.I.L., then recently has a Pistols reunion which has basically amounted to a Mountain Dew commercial. And Jello becomes an alarmist who can’t stop repeating himself…

I dunno, I guess when you’re young and you have an aggressive subculture going that’s anti-establishment, good things get teethed into. The thing that got me into the first generation of punk was the Anti-Nazi League. I was heavily with them. It was anti-fascist, which I was well up for. The Anti-Nazi League had these big festivals, and the feeling was quite good. When you’re about 15 or 16 years old and you’re with some 200,000 or so other people, getting together on a big march, it’s very exciting. At the time, we also had people like Cabaret Voltaire all around. We were into them, a lot of Northern Industrial funk, New Order, a lot of electronic stuff. We heard electro music from America and thought, “Wow! This is really good!” We were quite into Hi-NRG.

Were you into the Detroit techno when it started out? I ask because you’re calling from Detroit right now, so I wondered if you’d thought about it?

Were you into the Detroit techno when it started out? I ask because you’re calling from Detroit right now, so I wondered if you’d thought about it?

Well, the Detroit thing was later on. We actually met a taxi driver here last night who had done a few things with the Transmat label. I couldn’t tell you what was from Detroit and what was from Chicago, but I know the vibe that comes out of here. Awhile back, people played for us this “new stuff” called house that didn’t seem very different from the sequenced music we were already listening to. At the same time, it was exciting, though, that there was this “thing,” with a name, called house.

Do you think it improves a scene when it gets a name? When you have a “label” to put on a package?

I don’t know, it’s better for communication’s sake.

Do you think it helps the scene out technologically, since increased media attention means there’s more money around?

I know what you mean, but I wouldn’t necessarily feel that you’d have to call it a name. Categorizing is really for categorizing’s sake, it’s not for listening. It doesn’t matter a fuck to me whether it’s called house, acid, or jungle, etc. I mean, our music isn’t house, it isn’t techno, it isn’t anything. It doesn’t fulfill any of the categories. It only counts when you’re trying to communicate with others. For instance, somebody like yourself who’s writing about it uses labels to try to explain what music sounds like.

Can you describe last year’s Tribal Gathering for people in the States?

Basically, it’s a party in a field in the middle of nowhere. But when I say that, it has a different meaning in Britain than in America. I’ve noticed “in the middle of nowhere” here really is in the middle of nowhere. There’s a substantial town in England ten miles away, wherever you are. Anyway, it’s in an agricultural area, and it’s fenced off with different tents. It was a beautiful day and everyone had a good time, which is what’s important. There was a massive tent with us, the Prodigy, and Chemical Brothers. Then there were all these different classifications, like we were just talking about: They had a jungle tent, a house tent, an “erotica” tent that Moby got shoved into, and there was a tribal tent. The event ran for twenty-four hours, and it was quite amazing, really. You’ve got all these different categories spawned from house music, like branches of a tree. It was quite good to see it thriving in Britain ten years later, having this thing that was worthy of about 25,000 people coming down. It [Tribal Gathering] showed me the diversity of the styles of music that people are making with electronic instruments.

What happened to Tribal Gathering this time?

The local magistrates stopped it. There are a group of four or five magistrates who live in the area and decide whether or not you’ll be allowed to hold an event like this. They got a bee in their bonnet about electronic music, and they stopped it from happening. But now, [Tribal Gathering’s promoters] are trying to reschedule it, and they’re going to take it to Crown Court to a judge who’s supposedly “non-biased.” We all know that none of them are really non-biased, but it does stand more of a chance ’cause the Crown Court judge doesn’t live in the area. From the beginning, the promoters were trying to be nice. They went around to the local area in circumference of the site and offered them all costs-paid weekends in London, like with any hotel they wanted, and they could get into any theatre they wanted, if they objected to the event. Plus, what we’re talking about is a party in a field that doesn’t actually interfere with anybody. The music is contained within the tents to the extent that it’s not going to bother anyone two miles away. It was very thought out and there was a lot of care taken toward the locals, but there are people in the British government who have a serious problem with this type of music. (Phil’s sounding choked up over the issue.) With the Criminal Justice Bill…

Is it because of ecstasy deaths or stuff like that?

Well, I don’t know what it is. They claim it’s that, but they are very hypocritical, and I don’t want to get into that whole alcohol-versus-drug debate again. The Criminal Justice Bill is a new law that’s been enacted. One of the sections of the law is describing our type of music as “repetitive beat” music, and is sort of saying it’s to be outlawed. It’s a very Orwellian, fascist approach. It would be interesting to find out whether there’s been any other country in recorded history that’s actually made a concerted effort to describe a particular genre of music and then try to outlaw it. I don’t know whether it’s happened before, but I think it’s outrageous that our government has done it to this sort of electronic music. I mean every fucking music has “repetitive beats” in it from beginning to end, doesn’t it?

Maybe the government is scared that this more free-spirited scene is taking power away from it…

It makes them feel very threatened. Whereas punk, on the other hand, was very anti-establishment…

Punk was more containable.

Yeah, and you had an outfit.

The “powers that be” could just scoff at you.

You painted your hair and went around in ripped clothes…

There were few punks with any significant buying power. Someone with little money wouldn’t impose the same threat.

Yeah, exactly. I think this (“rave”) movement, as a subculture in Britain, is very undefinable in the sense that you don’t know who goes to raves and who doesn’t, because there’s no particular outfit. There’s a casual outfit which is very much based on American casual clothes; sportswear and stuff like that, which practically everybody who’s young is wearing in Britain right now, anyway. The subversiveness comes with the sense of not being bothered by anyone else, sort of being apolitical. It’s people who just want to go and escape from it all for a while, and the actual vibe is nonviolent. There’s rarely any kind of trouble, and (the movement has) only gotten larger since it started out. I think that’s what our government is frightened of, that people are doing it, left, right, and center, and it can’t really be controlled. They can say its about the “E” (ecstasy) thing, but I don’t think that’s really true. It’s just an excuse they use.

They don’t need to license (raves) for liquor. That takes away a big piece of leverage from the government.

Exactly. People aren’t drinking alcohol. If people are drinking and it’s at an official club, the government is getting revenue off it. As far as we know, they’re not getting any revenue from “E”. That’s a big reason for them to outlaw it, ’cause people don’t drink alcohol when they’re on “E” anyway. Y’know they love cocaine, ’cause you could just drink ’til the fucking cows come home. You can drink ten times more than you could normally, and you can go all night. I think they’ve got their fingers dipped into that pie, just like in America, really. So, back to the Criminal Justice Bill; there was this collaboration of militant and left wing parties who set out to fight it. There wasn’t only the “rave-y” aspect involved, there were a lot of other sections of that bill that were outrageous as well. A lot of people were fighting it, but it didn’t do any good. I think the approach that was used was one learned from the punk era. The punk era was essentially trying to put things right in a very aggressive way, and I think people came through that realizing that fighting the government doesn’t work. They just carry on doing what they want, lining their own pockets. They’re very small individuals. The Criminal Justice Bill dealt with New Age travellers as well.

New Age travellers? What are they?

Well, they’re modern gypsies, really. There’s a situation in England where it’s very hard for adolescents, 16-20 years old, who leave home to find housing. Just like everywhere else, you’ve got empty houses lying all over the place with people squatting in them. But the Criminal Justice Bill made it extremely hard for people to squat anywhere. When I first moved to London, I was squatting quite a lot. I mean, you need to do that, ’cause there isn’t anywhere else to go if you haven’t got a job. You can’t rent a place if you’ve got no money. There are still quite a few squats going, but since they’ve made it more and more difficult to do, as an alternative lifestyle and source of independence for younger people, they’ve ended up buying trucks and converting the backs of camper vans and travelling around in them.

Where does the “New Age” part come in?

I guess it’s essentially that these people are the type who are searching for new things, and are more likely to be into crystals and alternative medicines. It’s a bit of a generalization, but that’s where you got the name. The Criminal Justice Bill is trying to put a stop to that as well. In one part of England, if the police classify you as a New Age traveller, they can stop you from entering their county. I’ve got a camper van, so if I’m on holiday with my children, they could easily classify me this way and bar my entrance into their county.

Would they search your van for crystals and shit?

Yeah, exactly. (laughter) It’s absurd, really, that this is happening. Y’know in Britain, the fucking “land of justice,” it’s the land of bollocks, really.

Yeah, sounds like it. (laughter)

So what I’m trying to say is they create a situation that gives nobody the opportunity to leave home, so there are no alternatives. When people do find alternatives, they try to squash them, and so they just shift the problem, without thinking about the consequences of their initial clampdown. They’re just stupid. It’s like sweeping dirt under the carpet.

Do you play at more official clubs than raves?

We have to play at more clubs now because of the law.

‘Cause you don’t want to get thrown in jail?

Well, they can’t actually throw you in jail. What they do is confiscate your equipment, and you can’t get it back. Some friends of mine were starting a PA company and, at a warehouse party, they had all their speakers taken from them. It took them two years to get them back. That two years really screwed them up ’cause the speakers weren’t even paid for. Their livelihood that could have paid for the speakers was taken away when the equipment was confiscated. Because of these kinds of risks, it’s harder to get a PA company to do a free festival….