Switchblade Sisters

Switchblade Sisters

An interview with director Jack Hill

by William Ham

In cinema, as in everything else, there’s trash and then there’s Trash. The dear departed days of expolitation films, when drive-in fare and art-house flix kept intersecting like a warped Venn diagram, have bequeathed some masterful effluvia (as well as some of our greatest directors) to the ages. Some have taken on the quality of myth, while others, inevitably, have disintegrated into a nitrate mist. So it might have been with Jack Hill’s Switchblade Sisters, a picture that even failed with the detachable-speaker set upon its initial release, if The Man Who Wouldn’t Shut Up himself (Quentin Tarantino, natch) hadn’t rescued it from oblivion and brought it to the revival-house nabes where, oddly enough, it seems to belong.

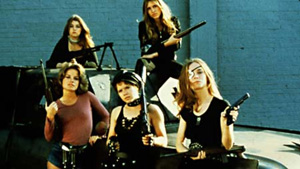

Switchblade Sisters is possibly the greatest post-apocalyptic/girl-gang/urban-warfare/bellbottoms-meet-shotguns-and-Maoist-black-chicks picture ever made. It swerves from a knife fight at a burger stand, to a comically over-the-top teen-reformatory sequence, to a roller-rink massacre, to a tank battle, to the ultimate, climactic catfight with a surplus of low-brow flair, buried highbrow thematic material, seventies social satire and truly unhinged performances (Robbie Lee’s Lace and Monica Gayle’s Patch distinguish themselves in this area, but all most bow to the surreally sadistic prison matron, Mom Smackley, portrayed by Kate Murtaugh, who, coincidentally, played a similar character with the same first name in 1982’s Dr. Detroit). You can look at this story as a camp classic, a pre-grrl feminist empowerment screed, or even a sly commentary on the nature of exploitation film itself, or you can ignore all subtext and just dig it as the ahead-of-its-time genre-defying golden garbage heap that it is. And maybe consider selling the naval-ashtray sequence to the anti-smoking hordes as a nice ad-campaign hook.

Given the above, you may just be wondering what kind of man makes a film like Switchblade Sisters. A lecherous, stogie-smelling hack, perhaps, with a head full of plugs and a permanent leer. Certainly such visions were running through my head as I was dispatched to the Four Seasons Hotel to speak with Jack Hill, Switchblade Sisters‘ director and the mastermind behind such legendary cheapo quickies as The Big Dollhouse, Isle of the Snake People and Foxy Brown. But one of the strange contradictions built into the explo explosion is that many of its practicioners actually cared about the medium of film and using the silver screen as a canvas for artistic vision more than their Porsche-driving, demographic-sucking Hollywood counterparts who were making supposedly “respectable” pictures, and Hill is as pure an exemplar of the former as you will find. Hill, whose fifteen-year career had him rubbing shoulders with the likes of Coppola, Nicholson, Chaney, and Corman (and let’s not forget Pam Grier), is a thoroughly friendly, relaxed gentleman who looks barely forty of his sixty-three years. He speaks with authority about literature and art and how he incorporated those elements into his films, yet he takes neither himself nor his work too seriously (no wonder he never made it in Tinseltown) and is rather amused with how his present resurgence came about. Here’s a little of what he had to say.

Given the above, you may just be wondering what kind of man makes a film like Switchblade Sisters. A lecherous, stogie-smelling hack, perhaps, with a head full of plugs and a permanent leer. Certainly such visions were running through my head as I was dispatched to the Four Seasons Hotel to speak with Jack Hill, Switchblade Sisters‘ director and the mastermind behind such legendary cheapo quickies as The Big Dollhouse, Isle of the Snake People and Foxy Brown. But one of the strange contradictions built into the explo explosion is that many of its practicioners actually cared about the medium of film and using the silver screen as a canvas for artistic vision more than their Porsche-driving, demographic-sucking Hollywood counterparts who were making supposedly “respectable” pictures, and Hill is as pure an exemplar of the former as you will find. Hill, whose fifteen-year career had him rubbing shoulders with the likes of Coppola, Nicholson, Chaney, and Corman (and let’s not forget Pam Grier), is a thoroughly friendly, relaxed gentleman who looks barely forty of his sixty-three years. He speaks with authority about literature and art and how he incorporated those elements into his films, yet he takes neither himself nor his work too seriously (no wonder he never made it in Tinseltown) and is rather amused with how his present resurgence came about. Here’s a little of what he had to say.

I suppose, like John Travolta, you have Tarantino to thank for your return to the public eye.

Yes, Switchblade Sisters is apparently one of his favorite films and has been for a long time. I didn’t know that. I’d only met him for the first time about two years ago. There was an AIP [American International Pictures, who along with Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, is responsible for the bulk of America’s exploitation output] retrospective at a theater in L.A. and I’d been asked to come and introduce Coffy [one of Pam Grier’s classics, which Hill wrote and directed], which was another of his favorites. He came up to me in the lobby and introduced himself – I knew his name but hadn’t seen any of his movies – and he had posters and record albums for my films that I didn’t even know existed that he wanted me to autograph, going on about how great the scripts I wrote were… how could I not like a guy like that? (laughs)

I’m sure you never expected this to ever see the light of day again, especially since if flopped originally.

I’m sure you never expected this to ever see the light of day again, especially since if flopped originally.

That’s true. I don’t think people quite knew what to make of it at the time. It was marketed very badly. The original title was The Jezebels, after the name of the gang in the film, and it performed poorly in the first region it played in. (They used to send their films out to one area of the country at a time because there were only a limited number of prints to use.) I had to change the name because they thought that people were confusing it with Jezebel, the Bette Davis film, but I think the real reason it failed was that the ad campaign was completely wrong for it and didn’t prepare people for the kind of movie it was. They marketed it like a fifties gang picture, which it certainly wasn’t. I had to change the title quickly, and Switchblade Sisters was the best I could come up with in five minutes. It was a desperation title. The funny thing is that it had already gone out to the second region under the original title because it was too late to change it, and it played rather well. But of course, by that point it was too late.

It certainly seems to wear better than most movies of the time.

Strange, really. The critics are talking about it as being post-modern, a feminist manifesto, comparing it to Samuel Beckett… I don’t know what to make of that. I’m not sure why anybody’d want to see it, to tell you the truth.

Well, it is a ’70s artifact, after all.

There really isn’t anything particularly ’70s about it, though…

…except the clothes.

Well, the clothes, yes. It was made in the last years of the Nixon administration, everything was looking rather bleak, everything was going downhill, and it was kind of a projection of where it might end up. That’s why it’s got that empty, desolate look about it. I suppose that’s what inspired the comment about it being Beckettville. I saw it more as sort of a female Clockwork Orange. It started out as an assignment to do a film about street gangs, which I didn’t want to do because I knew almost nothing about them and you really couldn’t make a realistic gang movie. For drive-ins, you’d really need beautiful blondes and such. So I decided to make it this kind of wacked-out fantasy, really have everything overplayed or else it wouldn’t work. You wouldn’t know it from seeing this movie, but I’ve done films where people underplay. I thought it deserved a really operatic, preposterous mise-en-scéne, but without the actors being aware of it.

At the same time, I was going for a real moving picture, character-driven and with a strong plot… when Lace and Maggie meet at the beginning, that moment is set up in such a way that you know you’re going to have that showdown at the end. It’s as inevitable as a Greek tragedy, not to overdo the comparison.

There’s been a renewed interest in exploitation films lately, but where would they go if you made them today?

I wouldn’t make those kind of films today! (laughs) I think what really killed the exploitation film was that the major studios started making those same kinds of films, only with big budgets and major stars. Alien is a good example. That would have been a Roger Corman picture in the fifties. As soon as they figured out that they could make money on those, we really couldn’t compete. Which is all right. I was never like Francis [Coppola] who, ever since we went to film school together, never questioned that he’d be the biggest and most famous director in the world, just never had a doubt. I never thought of myself in that class. He was very conscious about building his career up step by step, I was more interested in having a good time, bouncing from film to film, and I don’t regret a minute of it.