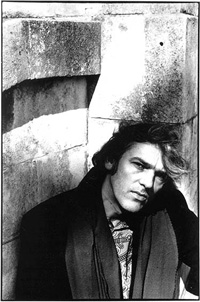

Robyn Hitchcock

Robyn Hitchcock

Moss Elixir (Warner Brothers)

An interview with Robyn Hitchcock

by Nik Rainey

Hard to believe that it’s been a full decade since Robyn Hitchcock emerged as the toast of the college radio crowd. (Harder still to believe that a decade ago the opinions of the college radio crowd meant something.) To understand his subterranean impact, consider the state of English music in the mid-eighties: much of the stuff that got skimmed across the pond at us was either intentionally (the Smiths, the Cure) or unintentionally (George Michael, Mission U.K.) depressing. The permanent sulk and the borrowed-leather-jacket sneer were the accessories to the fashion crime of the English pop scheme. (How unlike today, when English bands completely refrain from rock-creep posturing and boasting about the number of drugs they’ve taken and the number of birds they’ve shagged while on them. It’s a true oasis of… hey, wait a minute…) Enter Robyn, a thoroughly charming chap with a ready wit and an already prodigious back catalogue of bent pop songs, tinglingly catchy but lyrically demented, as if Syd Barrett were collaborating with Spike Milligan or the Beatles actually wrote songs about beetles. By 1987, his absurdist ditties had made him ubiquitous, turning up everywhere from the lowliest fanzine to the cover of Creem. His eccentric-uncle rep even landed him a deal with A&M. Unfortunately, the arrival of “alternative” as a commercial viability in the ’90s seemed to swallow Robyn’s brand of classic-songcraft-with-a-twist whole, and he seemed permanently relegated to the cult-artist sidelines, doomed to three-and-a-half star reviews in Rolling Stone for eternity. As he did in the early days of his post-Soft Boys solo career, he responded by disappearing from view. With the exception of Soft Boys’ and some pre-A&M solo reissues, and a three-song single he put out last year on K., he hasn’t released an album of new material since 1993. But Robyn’s returned to us at last, with a fresh deal with Warner Brothers and two concurrent releases: Moss Elixir, a gorgeous collection of mostly acoustic-based tunes, and Mossy Liquor, a vinyl-only limited-edition outtakes compendium. Both show him in firm command of his wayward muse, masterfully balancing a mature emotional vision with generous dollops of his characteristic humor. Mr. Hitchcock kindly took a half-hour of his time to speak to Lollipop, and dark green chunks of his wisdom are presented herewith.

Hello, Robyn? This is Nik Rainey calling from Lollipop in Boston, U.S.A.

Ah, yes. How is Boston these days? Is it steaming?

Oh, yes. Always is.

Good, good.

How are you, sir?

I’m all right. I’m steaming a little bit, but pleasantly so. Better steaming than steamed, I always say.

That’s always preferable. Well, it’s great to have you back. The new album’s wonderful. I guess the obvious question is why such a long hiatus between albums?

It just took a while to collect the songs and a while to collect the record deal. I wasn’t in a big hurry to do either. I didn’t have much lying around after Respect [1993], I had pretty much boiled myself dry and it took some time for new songs to appear. Once they did, it was two years of editing them, sticking them together and then looking for a deal, which finally happened last December. So, now, eight months later, you have the record. It’s rather like the gestation period for a baby elephant.

Eight months? Really?

No, sorry, two years – eight months is a third of the gestation period for a baby elephant.

I see. It’s funny – a lot of the pre-eminent songwriters of our time seem to be on Warners now – Elvis Costello, Lou Reed, and now yourself. I’ve wondered if maybe it was a trade – they lose Prince, they get you.

I see. It’s funny – a lot of the pre-eminent songwriters of our time seem to be on Warners now – Elvis Costello, Lou Reed, and now yourself. I’ve wondered if maybe it was a trade – they lose Prince, they get you.

No, I think if they traded me for someone it would have to be someone a bit taller than Prince.

Good point. So Moss Elixir is more or less a solo album – are the Egyptians [Robyn’s longtime backing band] no more?

Essentially, yes. After a certain age, it’s really sad to see bunches of men going ’round with their ankles tied together. You end up either tied together by enormous sums of money or tiny sums of money, like we were. Or you can be like the Stones or Pink Floyd, where you don’t even have to meet except on stage, and even then you can erect screens between you and the other members. Andy Metcalfe [bassist] became a parent in early ’94, so his focus was more on his family than touring, and I wanted to do an album that wasn’t written by committee. Certainly the last two were done that way, because we had outside producers, so I was only one of four or five people putting input into the record. But of course they’d be promoted as “the new Robyn Hitchcock record,” so the buck really stopped with me. The responsibility was mine so I thought I really should make the record myself. It’s very easy to allow yourself to be interpreted by other people. Some people become over-influenced or over-dependent on whoever presents them to the public and it changes rather dramatically. I think I do my very best work when I don’t have anyone else to rely on, nobody to tell, “Okay, you produce this bit, I’m going to the bathroom” or something. So this is the way I think I’m going. Andy and Morris [Windsor, drummer] and myself had a certain chemistry together that came from playing together for eighteen years, but because something’s always been so doesn’t mean it always has to be. We’re still in touch. Morris sings on a couple of tracks on the new album and I’ve played with Andy recently, but I don’t see it happening on a career basis again. I’d rather it be on a sort of occasional, celebratory basis. We’re not the Buzzcocks.

No hope of a Soft Boys reunion, then.

Well, the Soft Boys are different because we always had other members and it’s hard to get a hold of them. We tried once but we couldn’t get Kimberley Rew [second guitarist for the Soft Boys], his people kind of pulled the plug on it at the last minute.

What has Kimberley been doing lately?

I think Katrina and the Waves still have a record deal in a phone box in Scandinavia somewhere. They’re still churning stuff out, probably still funded by “Walking on Sunshine.” Kimberley came to my birthday party, actually, so we’re still chummy. The thing is that it was always more a musical than a social relationship between all of us to begin with. It wasn’t one of those things where you form a band with your mates. More like getting together with other musicians that you’ve had your eye on. Which I think is better because forming a band with your friends, is a good way to lose friends.

I know you were living in D.C. for a while, but I presume you’re back in England?

I’m in West London now. If you fell out of your plane as it was coming into Heathrow, you’d probably land on my roof.

I’ll try to avoid that. I don’t fly much, but I usually wear a parachute anyway.

You mean in everyday life? Very wise. Walking down the street, you never know when the whole thing might disappear from under your feet and you find yourself free-falling into the void.

I’m glad you understand. I get a lot of funny looks around the office. Anyway, in the late eighties, you were the underground demi-god for quite a while, in America at least. Did that affect you adversely?

Not as much as full-blown rock stardom would have. I don’t think I would have recovered from that. Being a little alternative demi-god was about all my head could take. Living in England, I didn’t see the effects of it so much, but there were periods when I probably got a bit big-headed, especially on tour. The world is there to see you and in the little cocoon of your tour bus you start to believe that you’re the center of everything. Both Andy and myself would get a little monstrous on tour. Not throwing things out of windows and such but our egos would get a bit swollen. I mean, you’re probably a little self-centered to begin with if you’re an artist, but in those circumstances you easily believe that everything is about yourself.

What about the press? Most of the articles I read about you at the time tended to dwell on the fact that you wrote a lot of songs about amphibians and insects, sometimes implying that you must be loopy on carpet cleaner or something to write like you do…

One thing I’ve always found insulting was the notion that if you had any sort of imagination it had to be drug-induced. There are drugs that will unhinge you a bit, I suppose, but to imply that you’re only able to think of things that aren’t in little two-by-four square blocks of thought if you’ve been tripping or smoking dope is really obscene. I didn’t write a lot of songs about fish and amphibians. Maybe one song in ten would contain a reference to an animal or a fish. But these creatures are there just as much as we are. They’re not buying records…

They’re starting to, I hear.

I hope so. But their lives are sort of dependent on ours. If we foul up the planet we take them with us. I think there’s a monstrous arrogance in humanity to think it can go ’round producing all these songs and not mention the other creatures out there. They weren’t necessarily metaphors, I was just mentioning them.

But I was aware that I was projecting a sort of wacky, ludicrous image of myself, and so around the time of Perspex Island [1991] I tried cleaning myself up a bit, growing up a couple of notches. I had a mixed amount of success with it – some people got bored and others said, “Oh, he’s no fun any more.” But I’m not some wacky little fruit singing about fish and insects, oblivious to everything else in the world. I don’t know much about politics, I don’t pore over the newspapers, but I can see how people feel, I’m here just as much as everyone else is and I’m horrified at what humanity is doing – I’ve never found it easy to be proud of being human. I think a lot of what’s fueled my work is a disgust with humanity and thinking, “Oh god, am I really one of them?” It’s like I’ve said before, “an angel’s head sewn on to a baboon’s body.” That’s why my stuff has never been pop music – pop music celebrates life and mine never really did. More like, “ulllgh, I can’t believe there’s more of this disgusting stuff inside me. Let’s have another look, shall we? Ooh, what’s this, rotting eggs?” and so on. You know, it’s that fascination with disgust you must have had when you were a kid.

I still have it.

Good lad. You pry the puffball open and all the spores come out, you challenge yourself to inhale the rotten meat in the bin liner… it’s not like it takes up 95% of my time, but it’s always there. But now, at least halfway through my life, I’ve settled into enjoying being human more. At long last I feel like I’m in the right place, as they say. Anyway, end of sermon, that’s the story.

Your lyrics don’t seem as heavy with imagery these days, they seem more straightforward. There’s this quote from William Burroughs to the effect that “The English can be wonderfully witty and entertaining all evening without actually saying anything.” Do you think you’ve struggled with that?

Yeah. I don’t know if it has to do with being English but it might. I’ve always found it easy to manipulate something out of nothing using words – I could write a whole song before I even knew what it was about, then I’d prune it away and have nothing. I’m not as keen on words as I used to be – I’m more interested in the tune and the emotion it creates. I’m really not bothered by the words, I just want to make sure they don’t get in the way and that they’re not too banal. I try to keep away from clichés and just find the tastiest words I can sing or the words that best fit the feeling of the song. I find it harder to write words now, I don’t write pages and pages anymore. Some of my early stuff, like “Wading Through A Ventilator” for example, that had reams of words! I always used to wonder why I kept running out of breath when I sang it! So since then I’ve been gradually cutting them down.

I don’t mean to be rude, but I have to go in a moment. There’s this other geezer lurking around, waiting to talk to me…

Oh, no, I understand. I really appreciate your talking to me today. Actually, I’ll have you know that this was a very prized interview. One of our other writers, who shall remain nameless [Mark Phinney], upon hearing that I snagged this chat, left quite a petulant message on my voice mail about it.

Well, if people are petulant you shouldn’t let them have too much soft food. You should put them back on Science Diet.

I’ll have to make that suggestion the next time I see him.

Yes. Do.