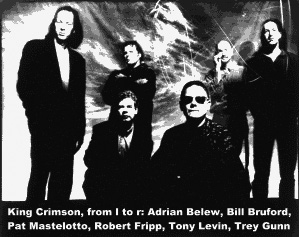

King Crimson

King Crimson

Thrak Attak (Discipline)

An interview with drummer Pat Mastelotto

by Lex Marburger and Bill Ham

This is more or less the third incarnation of King Crimson – how does Crimson Mach III compare in relation to the ’70s/’80s lineups?

I’d put them in three categories – the song-based category, the poppy stuff with strong lyrics and melody; the instrumental aspect, which is something Crimson’s always done; and third, something that ’70s and ’90s Crimson have most in common,improvisation. “Thrack,” for example, is wide open. It could go anywhere – from a string quartet to a wild Burundi drum excursion, whatever happens. It’s a question of reacting to the person standing next to you. Whoever takes the lead, the rest just fall in place behind him. That’s the premise behind Thrack Attack, which just came out on Robert’s Discipline label. It all came from our improvs last year.

I find the double trio format really fascinating and unprecedented in rock ‘n’ roll – the only precedent that I can come up with is Ornette Coleman’s double quartets.

Exactly. There’s also a classical composer, Durius Moreau, who composed for double string quartets. But I don’t think it’s been done in rock before.

How did you hook up with Crimson in the first place?

Specifically, I came to work with Robert on his tour with David Sylvian following their The First Day album, which Trey Gunn also played on. Jerry Marotta, who drummed on the album, kind of fell out before the tour. I heard about the gig, flew myself over to England, auditioned, then wound up on the tour that resulted in Damage, the live album. Afterwards, I kind of stuck around, and here I am.

What are your musical influences? You and Bill Bruford obviously have different approaches…

Yeah, I don’t have proper credentials. I don’t read music or know the proper drum rudiments, I’m more a seat-of-the-pants bar-band kid who’s played in bands all his life. Bill has much more of the jazz/symphonic percussion background, my roots are more in the Beatles, Zeppelin, the whole ’60s side. It works well in terms of Robert’s two-trio concept; the others sometimes joke that Bill’s Elvin Jones and I’m Ringo Starr. So together we’re Elvo or Ringvin or whatever they call us when they look in our direction.

Bill and I came up with a strategy pretty quickly in that we don’t try to play unison parts, like the Doobie Brothers, or the Jim Gordon/Jim Keltner Mad Dogs and Englishmen thing. We’re more like the Coleman approach where one guy plays electric and the other acoustic, only Bill and I both play hybrid acoustic/electric kits – so we don’t try to fall on the same beats in the bar or the same tamber. If Bill is playing something that relies on a lot of cymbals, I’ll jump into something with a lot of skin sounds; if he goes into metal tones, I’ll go into wood, and so on. I basically play in his holes. He plays a lot faster and with more finesse than I do, so it usually comes down to me playing the bombastic, heavy shit, and Bill skittering around inside it, like wheels turning within wheels. It tends to be very polymetric – we’ll pull different meters. He could play in 5 and I’ll play in 7, and there’s always a bit of math involved where you can figure out where we’ll coincide again. It might sound like chaos but there’s always a strategy that’ll lead us back home.

Is a lot of the studio stuff mapped out beforehand?

Is a lot of the studio stuff mapped out beforehand?

Robert’s very specific in his approach to making records. He prefers to play live; records come second. A lot of bands I’ve played with have the Sgt. Pepper/Abbey Road approach which is to create this masterpiece in the studio and then try to figure out how to play it live, if indeed they play live at all. Robert doesn’t dig that – he prefers that we work up material, go off and play it on the road for a month or so, and then go make the record. That way, we’ll have already played most of that material in front of people as a work in progress and gotten different feedback and ideas from the different atmospheres we’ve pla ayed it in. When we’re in the studio, it goes really fast – a couple, three hours to play a track where everybody plays together, a few hours to record vocals in the evening, then we pretty much move on. People get the impression that Thrack was a lot of overdubs. Not so, it just flew out, absolutely live – just get in there, fight it out, and see you at the other end.

What are the mechanics of the composition process? Do they come from jams or from preconceived musical or conceptual notions?

It could be all of the above. Typically, we could go into a room with no ideas, jam, and record it as we go. At the end of the day, we might have four hours of stuff from which we identify areas that we dug. Then we’ll either hone it down right there, or maybe give Adrian a half-hour’s worth of this feel or that and he might come back having rearranged it to suit the melodies and lyrics he’s come up with. Other times, Adrian, Robert, or any of us might come in with a piece we’ve mapped out for everybody to learn, with the understanding that the rest of us will “Crimsonize” it. Nobody comes in and says “This is the part I want you to play, Pat.” Even if I ask Robert for help, he’ll just say, “Play the right part.” The rest is just conveyed through looks and attitudes. One concept he has is that if we’ve heard or played it before, it has no place in our music. That’s what Robert and Crimson are all about – being open to surprises, accidents, things that are inappropriate to the norm. Everything is fair game.

The sense of discovery is very strong throughout the Fripp/Eno school of music.

That’s a phrase Robert will use in the studio – he likes to get “the moment of discovery” on the record.

One thing I’m really curious about is why you played the H.O.R.D.E. tour. It seemed like those other bands appeal to a different crowd than you.

What sort of crowd do you think that would be?

Uh… well, hippies. I mean, even in the hippie era, Crimson was not exactly embraced by those people.

Yeah, we’ll scare some of ’em. I played H.O.R.D.E. last year year with my friends The Rembrandts (no comment ed.). I’d played on all of their albums. It was kind of my last hurrah with them because Crimson keeps me pretty busy. Anyway, when we were trying to figure out where to tour this year, I suggested H.O.R.D.E. because it would mean playing to a different crowd than usually comes to our shows. We have a very loyal fan base, the kind that buys the record the day it comes out, sees every show, and that’s fantastic – but what about the people that would never hear about our band? We don’t get played on MTV or the radio, we don’t do pop singles, so I thought the H.O.R.D.E. crowd would be good for us. I always thought they were nice, receptive-to-anything-across-the-board-type kids – not a purely metal or a world beat crowd, they like diverse stuff. And it would be a challenge – we’d be going on early in the day, so we’d have no light setup, it’d be a different atmosphere than we’re accustomed to. And yes, some put their fingers in their ears and walked out, but some ran from the back to the stage to check us out, so it was actually pretty fantastic. And Robert enjoyed it, too. We were worried that he couldn’t deal with the lack of privacy. He’s a very withdrawn, private man, and here he is, sharing a dressing room with Neil Young and navigating through hallways full of people – and he dug it! Surprise, surprise! There he is, sitting in the wings, checking out Lenny Kravitz and liking it! Wow!

So I guess the H.O.R.D.E. m.o. is kind of like what you do with the music itself -ægo against the norm.

Well, I’m jaded. I’ve loved King Crimson since I was thirteen, but I’ve always thought that if you give ’em a chance, they’ll love us. Now I know that’s not entirely true after some of the reactions we got at H.O.R.D.E., but to my mind, the more diverse, the better. That’s the key and that’s why I’m here.