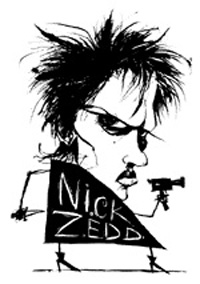

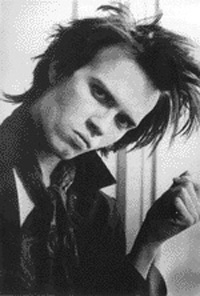

Nick Zedd

Nick Zedd

Totem of the Depraved (2.13.61 Publications )

An interview with Nick Zedd

by Michael McCarthy

Since 1979, Nick Zedd and his films have been praised by independent filmmakers ranging from Jim Jarmusch to John Waters, making him indisputably the world’s most famous living underground filmmaker. While many have sold out to the mainstream Hollywood system, abandoning all that was ever personal or unique to their style in exchange for a shot at fame and fortune, Zedd has attained a hefty portion of his fame for refusing to do just that. Not surprisingly, your chances of finding War Is Menstrual Envy, Police State, They Eat Scum, or any of his other films on a video store shelf in the near future are pretty darn slim. Despite this, Henry Rollins’ 2.13.61 Publications recently published Zedd’s autobiography, entitled Totem of the Depraved. You might suspect it would be a dreary, self-indulgent read considering the title and the poverty-stricken life Zedd has often been forced to live in order to finance his films, but it’s actually an amusing and pleasingly perverse account that should be appreciated by anyone with a fondness for honesty and, more importantly, sarcasm.

How did Totem of the Depraved come to be published by Henry Rollins?

I went to a poetry festival in Sweden in the late ’80s and Henry Rollins was there with Nick Cave and a bunch of other people performing. He saw me perform. I didn’t talk to him then, but he wrote me a letter. Encouraging me, I guess. I sent him the manuscript a few years later. He didn’t have the money to publish it back then. A few years later he read an obituary of me. It was a fake obituary. He thought I was dead then he rediscovered this manuscript and was like, “Aw, too bad he’s dead. I’d like to publish it.” Richard Kern told him I was still alive, then he contacted me and said he wanted to put it out.

Was there anything in particular that inspired you to write it?

First, it was when Sue, my girlfriend, moved out one day unexpectedly. I came home after driving the cab late and the place was empty because she took all her stuff. She was a junkie and we weren’t getting along too good. I had these mixed feelings because at the time I was living in a very small apartment and I was kind of claustrophobic anyway. So, I was kind of happy she left. I wrote this passage, which is in the book. It was like a fantasy sort of thing, having this wild, crazy sex. Then I went to Sweden for a second time that same year and met this girl named Frida who I spent a couple weeks with. She was pretty wild. When I came back, I wrote about it. I was trying to start a novel, but I started writing about what really happened with this crazy girl. I thought it was better than anything I could have made up. I started realizing that my life was interesting enough that I could tell true stories and it would make a whole book.

Tell us about your films.

Well, most of them I can’t describe in words, you know? Police State was one of the most popular ones. It was a black comedy about police brutality. I acted in it as the lead actor with Rockets Redglare. Flip Crowley is in it. He was an inmate in Attica, but in the movie he plays a police lieutenant. The last three movies I’ve done are double projection, where I have two projectors running simultaneously. They’re very colorful. I use all different kinds of music. There’s no linear narrative. The last one I did was closer to a structuralist film with a lot of fast cutting, montage. It was totally silent with no music. I’d like to show these movies in Canada, but every time I’ve tried I’ve been prevented by the Canadian government. The only time any of my films ever got shown was at the Festival of Festivals. I guess they got permission or something. That movie was Whoregasm, one of the more pornographic ones I’ve done. But I really haven’t had the money to return to Canada and nobody has invited me. No one seems interested in challenging the antiquated legal system there, which prevents Canadian people from seeing more cutting edge type movies.

How did working on Totem of the Depraved compare with making a film?

This guy Darius James, who’s a writer, had met me and I was looking for work. He told me that maybe I could write for Penthouse Magazine or Penthouse Letters. So, I went back and looked at this passage I did on Frida and sort of reedited it. That came out really easy. I gave it to them and got paid 1800 dollars. And it was only four pages. I thought, this is great, I can just sit in my room and write for a couple hours and get all this money just for describing sexual fantasies. That was like an immediate reward. With films, it takes a lot longer. You have to cast it and collaborate with other people. It’s a totally different process. Writing is a lot more isolated. Writing screenplays is similar.

Your company is called Penetration Films. For shock value?

The word penetration has multiple meanings. I like to penetrate people’s consciousness. But it could also refer to sex or other things.

Tell us about “The Cinema of Transgression.”

I came up with that term. I thought it up after I had done They Eat Scum in 1979. I wasn’t getting much attention from the press so I thought it would be useful if there was a movement. At the time there weren’t any other filmmakers doing films like I was that had a lot of shock value. I waited and I thought that if it ever happened, I’d use this term. In 1985, Richard Kern, Tommy and these other people started making movies. I started putting out this magazine, The Underground Film Bulletin, and I wrote a manifesto for The Cinema of Transgression using pseudonyms. That got a lot of attention in the press. People that otherwise would have ignored all of us. There’s strength in unity.

Do you aspire to make films that get a wide release or do you prefer to remain underground?

Do you aspire to make films that get a wide release or do you prefer to remain underground?

If I can maintain control, I would continue to make movies with bigger budgets to reach a wider audience. But I know in Hollywood there’s this work fare system in which people with no talent rewrite scripts. You get a whole committee that waters down a concept so that it’s unrecognizable by the time it comes out. I’m not interested in being part of that. I think it’s really important not to compromise.

Do you find that you’re limiting your audience by making films that are so personal?

Well, I have to wait for this stupid little world to catch up, you know? When you’re ahead of your time, that’s the way it is. I’m not interested in holding back or pandering to the lowest common denominator in order to become successful. It doesn’t seem like originality is given much of a reward nowadays. Imitation and copying are what seem to be fashionable now. Lots of remakes, which I’m really bored with.

Do you feel that film critics generally take your work too seriously or not seriously enough?

Not seriously enough. I think they’re lazy. Most of them are just a bunch of human Xerox machines. They read a bunch of articles in your press kit and paraphrase them. They’re terrified of having an opinion of their own. They don’t do enough analysis, examining the ideas in the film. To me, a film is a collaboration between me and the person that sees it. Half the job is for the person to analyze and come up with what it means to them. That’s pretty rare.

Do you ever find it frustrating to deal with actors, that they don’t comprehend your metaphors and such?

Yeah. Sometimes somebody will make a comment like, “He doesn’t know what he’s doing.” I don’t care what they think. Sometimes I don’t know what I’m doing, but then it comes out good anyway. Usually the people I work with are pretty understanding, although it’s strange when they aren’t. Like Annie Sprinkle. Even though I thought she was really great in War Is Menstrual Envy, she was kind of impatient with our shooting technique. We were trying to light it right and get a really good effect with the costumes. It seemed like she was giving us a time limit. It was like, “OK, you’ve got an hour left and then you’ve got to sweep up the floors.” All this stupid shit. I’m thinking, that’s not a very artistic mentality. But most of the people I work with are not professionals anyway so most are thrilled to be in a movie. They just go along with it because they want the attention.

Do you act in all of your films?

Just a few of them. With Police State, I didn’t even intend to be in it, but the person I cast was homeless and sleeping on the subway and totally unreliable. Didn’t show up for any rehearsals and at the last minute he wasn’t there at all. So, I decided to play the part. I’m glad I did because it made it more of a challenge to act and direct, but I would prefer not to be in them if I can find someone who’s reliable. It’s hard to get people when you’re not paying them.

Have you appeared in anyone else’s films?

Yeah. I’ve been in quite a few movies. I was in this movie called What About Me with Johnny Thunders and Richard Hell. I was in Joe’s Apartment. I had a very tiny part in that. I’ve had bigger parts, though. I was in this thing called No Such Thing As Gravity and I was in Shadows in The City by Ari Roussimoff. I’ve been in a bunch of Richard Kern’s movies. These are underground movies I’ve done.

Will Henry Rollins appear in any of your upcoming films?

That’s a possibility. I’ve talked to him about that. First, I have to get more money. I’m really broke. Right now I have about five dollars, but I’m going to tour Germany in the fall and I’m hoping to make some money there. Also, the first royalty statements will come out on the book and I’m hoping something’s gonna come in on that.

What was the last Hollywood film you enjoyed?

Natural Born Killers, because that was so influenced by my last two movies. It was like watching one of my movies up there.

You didn’t feel ripped off?

I guess it was an homage. Everybody’s influenced by something, right? I guess it’s flattering that Oliver Stone would be influenced by me.

What’s your opinion of today’s film festivals?

There’s way too many of them, for one thing. I’m really against charging entry fees to filmmakers when they should be paying them rental fees for showing their films. A lot of these festivals seem to be an excuse for trendy, wannabe filmmakers to meet with jaded, young socialites. To go out and party and put in their hair gel. There’s one festival, the Chicago Underground Film Festival, I respect them. I think they definitely have a more progressive attitude. But places like the Sundance Film Festival are not independent at all. I know filmmakers whose movies have been excluded from it which were excellent films. Then I see these other ones that get these awards and they’re just so bad. And, also, this term “indie” really gets on my nerves. When you meet someone at a party, they say, “I want to be an independent filmmaker.” I feel like saying, why don’t you just want to be a filmmaker? It’s sort of destroyed what it’s supposed to be celebrating. To me, their budgets are still exorbitant. To call them independent films is very exclusionary.

In your book, you talk about the censorship that goes on in different countries. How does the United States size up these days?

Well, you have censorship by omission, where you’re ignored completely. Especially by so-called alternative sources of communication like the free newspapers. Television is obviously in the hands of corporations. Unless you have massive amounts of money, you don’t get any attention. If you’re underground, you just get your ideas stolen. It’s not necessarily that much better here. At least you don’t get thrown in jail. Or you’re less likely to. It depends where you live, I guess. If you live in Florida, you could get busted like Mike Diana did for drawing comic books. In New York, they don’t bother you very much. You just get ignored.