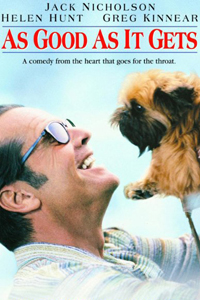

As Good as it Gets

As Good as it Gets

with Jack Nicholson, Helen Hunt, Greg Kinnear

Directed by James L. Brooks

Written by Mark Andrus, James L. Brooks

(Sony)

by Jamie Kiffel

As Good as it Gets features a constantly surprising, whip-twisting plot filled with start-stop false climaxes and sinus-flushing hilarity, and reeled in the two most glamorous Academy Awards (Best Actor, Jack Nicholson and Best Actress, Helen Hunt). With a lengthy skein of reviewers yammering to the point of drool in order to back up these accreditations, it seems unnecessary for me to take this space to further laud what will probably be referred to in the future as one of the best films of this decade. I would rather explore what it is about the film that makes it thematically unique, and thus, so important.

Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson) is, as his gay neighbor defines him, “an absolute horror of a human being” who gleefully tortures what may be the cutest dog on film and tells his favorite waitress, Carol (Helen Hunt), that her ailing son will probably die soon. Despite her deeply detailed performance as a hard-edged and troubled young widow, it is not Hunt who unceasingly and sometimes sufferingly holds our attention throughout the film, nor is it Simon (Greg Kinnear) with his tear-studded pleas for compassion and his complex love for Carol. It is only Udall who, with his fear of stepping on cracks, terror of restaurant flatware and disgust with human beings in general, succeeds in holding the audience by the throat and simultaneously inspiring it to pucker up for a kiss. Nicholson is a hyperreal creation, a fairy tale creature too evil and too equally fascinating to be true. He is the ideal personification of New York City, and it is this which transforms his character into a superstar.

Like Melvin Udall, New York is thrilling, compelling, and horrifying at once. It draws into its grip dreamers and doers alike, distributing evisceration to some and lavishing munificence on others, with no measure of predictability. It favors no one. After tossing Simon’s dog down the trash chute, Udall warns Simon never to knock on his door, even if, for a protracted period, it exudes the aroma of rotting flesh. He is phobic of Blacks (the city certainly is no favorer of minorities), and he senses filth everywhere, scowling and swearing as his body accidentally comes in contact with someone else’s. Likewise, New York is the focus of confusion and sickness, breeding filth on the sidewalks in front of Fifth Avenue boutiques. Udall wastes copious amounts of disposables (soap, utensils, dishes), encompassing the rich wastefulness of the city, in the face of the needy (in Melvin’s world, the needy include Simon, who is mugged and rendered homeless, and Carol, whose son remains chronically ill because she cannot afford sufficient care for him). Melvin is, appropriately, a writer: his only passion is for telling tales of love and emotion that, like New York, wriggle into others’ gray matter, leaving him untouched and unmoved.

Melvin starts to hand out gifts to those who are close to him, beginning with Carol, upon whom he bestows one of the best doctors in the city. He refuses to be thanked. Carol’s impulse is to tell Udall that he is the greatest man alive, but he makes it clear that his only prerogative was to free Carol from caring for her son so that she could wait on Udall at his favorite restaurant, and to entice her to sleep with him. Udall offers to drive Simon cross-country to meet his parents and to beg them for money, but his reason turns out not to be kindness, but the excuse to take Carol along in hopes that she will sleep with Simon, miraculously turning his dispicably gay self straight. When Udall finally gives Simon his own room in Udall’s apartment, in spite of Simon’s tearful thankfulness, we see that Udall’s real reason for helping is to demonstrate to Carol that he cares about her friend, and thus to win a place in her bed.

Melvin gets away with saying and doing the terrible things he does because he possesses no traceable morality. He tells Carol, after she spends all night tending her sick son, that the dark circle under her eyes make her look like an old woman. He mocks Simon’s mangled face following Simon’s mugging. As the same people whom he tortures come to adore him for his gifts and his help, the classic tale of New York is told: Those who are kicked and destroyed by the city stop cursing and begin loving it as soon as they make their first big break there. Appropriately, Udall’s only real trace of love is shown for a dog: He favors a dumb and subservient animal over a rational human being.

It would be wrong to say that it is this complicated drawing of Udall’s character that makes him so special, without paying proper homage to Nicholson’s portrayal of him. Without Nickonson’s classic, slow brow lift and thousand watt grin, I might never be able to smile back at the awful Udall. In the end, it is not for his money, his uniqueness, or his attentions that Carol falls for this soulless man. It is for his devilish lip-curl, as thrilling and insidiously-intentioned as every electric bulb in every peepshow window on Forty-Second Street.