Movies: Shots in the Dark

Movies: Shots in the Dark

by Adam Haynes

The only thing remotely intriguing about last year’s American Beauty is its critical and commercial success. Naturally, most of this can be blamed on the colossal marketing campaign which was launched simultaneously and with Roman calculation at the art-house and plex-crowd. But marketing only goes so far, there has to be something inherent about the movie which sparked some cord, ignited some pent-up zeitgeist…

My answer came more recently while I was watching Simpatico. I found myself thinking about American Beauty. At first I was baffled. Simpatico, starring Nick Nolte, Jeff Bridges, and Sharon Stone, is the story — based on a Sam Shepherd play — of three middle-aged people dealing with the angst and guilt of a horse-fixing, blackmail scam they committed twenty-some-odd years ago. Superficially, it has nothing whatsoever to do with American Beauty. But at their root, both movies are about people aging into their middle years who start reacting and then eventually trying to atone for all the shallow, insipid decisions they’ve made regarding their lifestyles and personal morals.

In short, it looks as though a new exploitation genre’s being born. Call it Baby Boomer Purgesploition. This extremely marketable age group who, back when they were kids needed movies like The Graduate and Easy Rider to give them easy ways to thumb noses at their parents, now apparently are quite vulnerable, ready, and eager for films like American Beauty and Simpatico — which only failed because of its poor marketing — which vicariously offer appeasement for those who have turned into their parents, only with greater hypocrisy and less taste.

In short, it looks as though a new exploitation genre’s being born. Call it Baby Boomer Purgesploition. This extremely marketable age group who, back when they were kids needed movies like The Graduate and Easy Rider to give them easy ways to thumb noses at their parents, now apparently are quite vulnerable, ready, and eager for films like American Beauty and Simpatico — which only failed because of its poor marketing — which vicariously offer appeasement for those who have turned into their parents, only with greater hypocrisy and less taste.

* * *

The best movie to be released so far this year is, hands down, Holy Smoke. In it, Kate Winslet gives a powerhouse performance as a young, middle-class Australian who starts following a guru in India, and then gets duped into coming back home where her family’s hired a deprogrammer, Harvey Keitel, to bring her back to her senses. As it turns out, Keitel finds himself without an assistant and ends up getting way in over his head. Their situation gets wildly out of control, which ends up bringing out greater truths concerning the nature of relationships and spirituality.

Of course, you wouldn’t know this to read all the interviews with director/writer Jane Campion that came out during the movie’s national release. In them, Campion seems only capable of spewing out two-dimensional sloganism about the unique female experience and how annoying men are; the sort of tenured feminism that feels as tired as it is old. Her movie is clearly about the psycho-sexual power dynamics that go on between men and women, but more importantly, it’s about how tacky our modern culture is and how honesty is only obtained by pushing the sleaze further. Campion the writer has never really understood character very well and, as her interviews make painfully obvious, she understands men even less. This is the reason her male characters tend to be the weakest links in her films — not because of her political stance, as her interviewee loudly attempts to suggest. Her real gift is displaying the brand conventions of “trash culture,” the aspects of modern life which normally most cinema tries to conceal. This is what makes Holy Smoke and her debut, Sweetie, so masterful. Likewise, it’s the lack of gritty, cynical, and humorous edge which causes her to flounder so badly and end up so banally P.C. whenever she does a “serious” period piece, as with The Piano, Portrait of a Lady, and Angel at my Table.

Of course, you wouldn’t know this to read all the interviews with director/writer Jane Campion that came out during the movie’s national release. In them, Campion seems only capable of spewing out two-dimensional sloganism about the unique female experience and how annoying men are; the sort of tenured feminism that feels as tired as it is old. Her movie is clearly about the psycho-sexual power dynamics that go on between men and women, but more importantly, it’s about how tacky our modern culture is and how honesty is only obtained by pushing the sleaze further. Campion the writer has never really understood character very well and, as her interviews make painfully obvious, she understands men even less. This is the reason her male characters tend to be the weakest links in her films — not because of her political stance, as her interviewee loudly attempts to suggest. Her real gift is displaying the brand conventions of “trash culture,” the aspects of modern life which normally most cinema tries to conceal. This is what makes Holy Smoke and her debut, Sweetie, so masterful. Likewise, it’s the lack of gritty, cynical, and humorous edge which causes her to flounder so badly and end up so banally P.C. whenever she does a “serious” period piece, as with The Piano, Portrait of a Lady, and Angel at my Table.

* * *

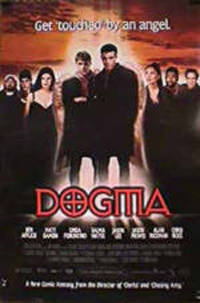

One of the most annoying parts of last year’s Dogma is the direct reference it makes to other movies. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. Paul Thomas Anderson did the same thing with his not-as-bad, but equally overrated, Magnolia.

One of the most annoying parts of last year’s Dogma is the direct reference it makes to other movies. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. Paul Thomas Anderson did the same thing with his not-as-bad, but equally overrated, Magnolia.

Why is it that young filmmakers are making these direct references to other movies in their own movies, and why is it that this sort of activity is considered “hip” and “fresh”? Don’t these filmmakers understand that the purpose of a movie is to tell a story that will resonate and connect with pieces of the greater world, to add layers and richness to the overall experience? Don’t they understand that when your movie is just about another movie that it ends right there, that there’s no further resonance? Don’t they get that by deliberately mentioning the movies they’re ripping off, or self-consciously addressing, they’ve only gotten tricky and therefore less esteemable?

We find ourselves at a point in history where there’s a lot of self-consciousness in the pop culture, a lot of irony. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that this is nothing more than your basic phenomenological Chinese finger trap. The more you ironically address your own self-consciousness, the more self-consciously ironic you become. It’s semiotic dead-end. Possibly one of the reasons the whole ironic self-conscious fad is so popular among current young adult filmmakers is that it’s so meaningless, and therefore very easy to get pretentious about without having to worry about how pretentious you’re getting. Who knows?

I read an interview with Dogma’s Kevin Smith where he said that all he’s doing is writing about what he and his friends talk about; that he’s just reflecting what’s going on. Oh please… Like Paul Thomas Anderson, he’s taking the easy narrative road because 1) he knows he can get away with it, that people will actually “think” there’s more going on, and 2) it’s probably all he’s capable of.

I read an interview with Dogma’s Kevin Smith where he said that all he’s doing is writing about what he and his friends talk about; that he’s just reflecting what’s going on. Oh please… Like Paul Thomas Anderson, he’s taking the easy narrative road because 1) he knows he can get away with it, that people will actually “think” there’s more going on, and 2) it’s probably all he’s capable of.

Why is this sort of thing getting what has to be seen as positive feedback from the masses? That’s easy. Robert Altman once said something about how all people want to see in movies is something new and different. Most people getting jazzed by Dogma and Magnolia are simply responding to what at this point feels new and different, and therefore superficially exciting. What these fuzzy little lemmings don’t get is that this new and different trend is just another disposable fancy box, empty on the inside. Re-watch either of these movies two years from now, late at night on the USA network, and you’ll find all the once-hot’n’yummy popcorn is suddenly old, linoleum kitchen tiles. Scratch your head in wonder…

…and for the record, even if Dogma and Magnolia hadn’t opted for the “flashy,” “cool,” “post-modern” self-referencing, they still would’ve been miserable movies. Dogma because of its characters, who all sound exactly the same, are whiny, expositional and passive, and stumble through a story structure so flimsy and gimmicky that it makes an episode of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers seem mature and focused. Magnolia because Anderson stole practically everything directly from Altman’s Short Cuts, and still manages to waste three hours wallowing around in melodrama.