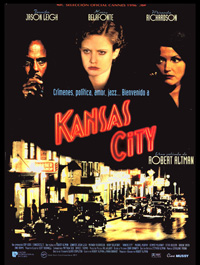

Kansas City

Kansas City

with Jennifer Jason Leigh, Miranda Richardson, Harry Belafonte

Written by Robert Altman, Frank Barhydt

Directed by Robert Altman

by William Ham

Robert Altman describes Kansas City, his thirty-first feature, as a “jazz memory.” True enough – an Altman film bears about the same relationship to ordinary cinema that, say, Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” does to Julie Andrews’ version, and his latest opus is no different, meandering through his riffs with the loose confidence of a master saxman weaving glorious solos over a 16 fpm backbeat. The main difference here is that, though the action takes place over two nights in 1934, the mood evoked is less the ebullient swing of that period than the darker bop that crept in with the Atomic Age.

Altman wastes no time with lengthy setups – in the very first scene, Blondie O’Hara (a very conspicuously brunette Jennifer Jason Leigh) bluffs her way into the home of Henry Stilton (Michael Murphy), an assistant to President Roosevelt, and quickly kidnaps his laudanum-addicted wife Carolyn (Miranda Richardson). Blondie, a movie freak with a serious Jean Harlow obsession, hopes that she can use the Stilsons’ connections to get her boyfriend Johnny (Dermot Mulroney) out of the clutches of Seldom Seen (Harry Belafonte), an elusive black gangster he unwisely upset by robbing one of his high-rollers (in blackface, no less). With Carolyn in tow, Blondie sets out on a long, circuitous journey through the city, keeping her charge out of sight while attempting to bring her outlandish plan to fruition while Johnny stays ensconced in Seldom’s all-night jazz club, awaiting his fate. And waiting. And waiting.

The brilliance of Kansas City lies in Altman’s steadfast refusal to adhere to cinematic conventions, even the ones he himself created. His usual ensemble casting has been pared down considerably, the usual Altmanic overlapping dialogue is nearly nonexistent, and standard narrative has been exchanged for character-driven drama. Leigh has yet again pulled off the marvelous trick of turning a series of annoying mannerisms into a compelling, tragic portrayal, and Richardson is both comic and sad as the politician’s wife. Unlike most films, where a bond would form between these two disparate women, Altman takes the gamble of never having the two truly connect – Carolyn’s opiated bewilderment and Blondie’s stubborn single-mindedness keep eluding each other, two forms of oblivion separated by chasms of class. Belafonte is chilling as the rasping Seldom, telling his driver an awful racist joke while his henchmen brutally murder another of his drivers a few feet away. The design of the film (by Altman’s son Stephen) is impeccable, bringing this corruptably prosperous city in the heart of the Depression to life, right down to the peanut shells on the barroom floors. And details that in the hands of, say, Robert Zemeckis, would be played for coy comedy are wisely underplayed – see how long it takes you to figure out who the young, sax-wielding boy wandering through the film is. Kansas City is hardly the feel-good film of the summer (although the sax duel in the middle of the film is quite enjoyable) – the violence has a flat inevitability missing in this bang-bang-yuk-yuk era and the conclusion is refreshingly dark and ambiguous. When Carolyn throws away her laudanum bottle in the final scene, it comse off at first like she’s discarding her life of ignorant bliss. Then it occurred to me, the bottle may just have been empty.