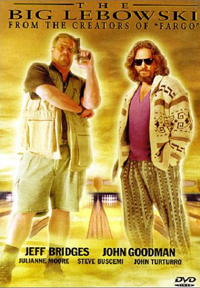

The Big Lebowski

The Big Lebowski

The Imp(ortance) of the Perverse

with Jeff Bridges, John Goodman, Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi, John Turturro

Written by Joel and Ethan Coen

Directed by Joel Coen

by William Ham

One of the primary facets of genius, I’ve come to believe, is perversity: the willingness to lull the unsuspecting into a false sense of security and then – BAM – a quick one across the bridge of the nose with a two-by-four for no other reason than to gloat over the stunned look on their face. Part of it derives from an indifference edging into loathing of the audience, making practically a moral imperative out of it: I don’t care, and I’ll do whatever it takes to show you I don’t care. Over the last thirty years or so, the ranks of the perverse have swelled and splattered all over the map, solipsistically following their muses into dark, shadowy places and somehow enticing their minions to tag along. In music, there’s post-bike crash Dylan, post-Transformer Lou Reed, post-Armed Forces Elvis Costello, and post-natal Prince, all of whom owe what potency they still possess to the fact that even their staunchest acolytes are bewildered and infuriated by at least half the things they’ve done. But music, where only relatively tiny amounts of people and money are involved, is one thing. It’s the high-stakes world of mainstream motion pictures, where every body of work is covered with too many fingerprints and eccentricities aren’t punished lightly, that attracts a special breed of pervert – the kind so skilled at charming dozens of executives, moneymen, and crew members into helping realize some monumentally fucked vision that one wonders why they didn’t start a cult instead and reap the tax breaks. Obviously, people like Spielberg and Scorsese don’t count among that number; even when they stray from their ascribed paths, it’s obvious they want people moved, uplifted and/or awed and will use every drop of passion in their reservoirs to do so (and amazingly, Spielberg was the first of the two to get cynical about it, as The Lost World showed). Oliver Stone and Spike Lee, for all their supposed radicalism with form and function, are exactly the same (if not more so – I’ve learned to wear hip waders whenever I go to one of their films to keep from sloshing in the pools of blood, sweat, and tears that they always leave behind). Even Lynch and Cronenberg, our two weirdest auteurs, have never really broken faith with their crowd (not intentionally, at least) – you come to see strangely italicized performances, compositions that play as if submerged in three feet of water, and sexualized deformities, and dammit, that’s what you get!

Which leaves only a select few, blessed with the talent and ability to make classic films that cut across genre and audience boundaries, but also a nasty streak that inspires them to abandon those they so painstakingly seduced. For my money, no one has yet topped the work of Brian DePalma, whose pranksterism was his watermark in his pictures up to The Untouchables (it was there in that film, too, but in ways more iconic than iconoclastic, like recasting the “Odessa Steps” sequence in a train station or filling Sean Connery fulla lead), but atoned for his failed attempts at maintaining “serious director” status (Casualties of War, The Bonfire of the Vanities) by turning around and showering the nabes with the blunderbuss of audience contempt that was Raising Cain. Like most, I hated the film the first time I saw it, then quickly came to realize that here was a picture worthy of a grad-school film course: every compound implausibility, haphazardly layered flashback, and self-mocking Hitchcock misquote was lovingly arranged with the artistry of a psychotic florist, and when I realized that he set up a tracking shot as long and elaborate as anything Welles or Altman designed, only to have it go absolutely nowhere, I knew the man was a genius. Only a genius would bother to piss off his patrons so blatantly.

Which leaves only a select few, blessed with the talent and ability to make classic films that cut across genre and audience boundaries, but also a nasty streak that inspires them to abandon those they so painstakingly seduced. For my money, no one has yet topped the work of Brian DePalma, whose pranksterism was his watermark in his pictures up to The Untouchables (it was there in that film, too, but in ways more iconic than iconoclastic, like recasting the “Odessa Steps” sequence in a train station or filling Sean Connery fulla lead), but atoned for his failed attempts at maintaining “serious director” status (Casualties of War, The Bonfire of the Vanities) by turning around and showering the nabes with the blunderbuss of audience contempt that was Raising Cain. Like most, I hated the film the first time I saw it, then quickly came to realize that here was a picture worthy of a grad-school film course: every compound implausibility, haphazardly layered flashback, and self-mocking Hitchcock misquote was lovingly arranged with the artistry of a psychotic florist, and when I realized that he set up a tracking shot as long and elaborate as anything Welles or Altman designed, only to have it go absolutely nowhere, I knew the man was a genius. Only a genius would bother to piss off his patrons so blatantly.

If you buy my definition, then with The Big Lebowski, Joel and Ethan Coen have finally made their geniushood official. Some of us knew they had this in them all along – they hinted at it by following up the moody noir, Blood Simple, with a hyperactively shrill farce (Raising Arizona) which featured mud-covered convicts speaking in long, polysyllabic sentences and “Ode to Joy” arranged for banjo; they nudged a little closer with a brilliant period piece (Barton Fink) where the protagonist is pathologically unable to accomplish anything; and they swept the prelims by enlisting the very producer (Joel “Die Hard With An Aneurysm” Silver) they had viciously parodied in the previous film and an astronomical set-design budget to make a $13 million movie about how the hula-hoop might have been invented (The Hudsucker Proxy). But even then, the Coens were still generally thought of as cold, clever movie nerds, obsessed with the science of the art and forsaking the heart, and therefore the kind of people from which such moves would be expected.

And then along came Fargo. Part of the reason that film carries such weight (it made the AFI’s 100-best-films-of-the-century list a mere two years after its release, don’t forget) is that nobody expected the boys were capable of delivering a picture so unbeholden to genre convention, so tightly structured (their trademark eccentricities-into-grotesqueries are there in force, but somehow augment rather than overwhelm the plot), so… emotional. Some have argued (I, personally, disagree) that Fargo represented the first Coen film populated by characters that could be construed as flesh-and-blood humans rather than the creation of an overheated screenwriter’s psyche – not just Frances McDormand’s (justly) praised pregnant sheriff, but also William H. Macy, who pulled off the equally difficult role of a man slowly imploding from guilt, fear, and a dozen layers of deception. Such a pitiful (and pitiable) villain is a rare beast indeed in American cinema. With a series of broad brushstrokes and a minimum of vocabulary words (make a drinking game out of the number of times the word “Yah” is heard and you’ll slip into a coma before the end of the second reel), the Coens pulled themselves out of cult semi-oblivion and into the vanguard of American filmmakers with one concentrated tug. Our mistake may have been expecting that they’d happily remain there.

In my most gleefully misanthropic moments, I like to imagine that Joel and Ethan only made Fargo in the first place so they could soften the rubes up for the winding stroll through the (be)wilderness that is The Big Lebowski. Of course, that’s ludicrous, but then again, I wouldn’t put it past them – in their early days, they were known for such clever-boyish activities as making up titles and plots for non-existent films (example: Adolf “Terry” Hitler, which speculates about what the most infamous figure of the century would have been had he been born in L.A. and become a superagent) – a few years, a little success and experience under their belts, and their ambition having grown commiserately, why not contrive a great work of art just to trick people into falling for a leviathan piece of self-indulgence? Was it they who spread around the pre-release hype heard in some circles that this picture was “better than Fargo“? Or is there a much simpler (if still perverse) explanation for it all – that the sibs suffered an allergic reaction to across-the-board success and decided to clear their heads of all the oddball characters, unlikely situations and bizarre lines of dialogue being delivered in even more bizarre accents that were clogging up their brains like so much mental mucosa?

In my most gleefully misanthropic moments, I like to imagine that Joel and Ethan only made Fargo in the first place so they could soften the rubes up for the winding stroll through the (be)wilderness that is The Big Lebowski. Of course, that’s ludicrous, but then again, I wouldn’t put it past them – in their early days, they were known for such clever-boyish activities as making up titles and plots for non-existent films (example: Adolf “Terry” Hitler, which speculates about what the most infamous figure of the century would have been had he been born in L.A. and become a superagent) – a few years, a little success and experience under their belts, and their ambition having grown commiserately, why not contrive a great work of art just to trick people into falling for a leviathan piece of self-indulgence? Was it they who spread around the pre-release hype heard in some circles that this picture was “better than Fargo“? Or is there a much simpler (if still perverse) explanation for it all – that the sibs suffered an allergic reaction to across-the-board success and decided to clear their heads of all the oddball characters, unlikely situations and bizarre lines of dialogue being delivered in even more bizarre accents that were clogging up their brains like so much mental mucosa?

We may never know the answer, and that enigma is part of what makes Lebowski so much fun to watch. It doesn’t hurt that the main actors create full-blooded characters and that each seems to be operating in their own separate universe. Jeff Bridges’ perpetually-stoned and completely unambitious Dude, John Goodman’s gung-ho Viet vet Walter, Julianne Moore’s pretentious “vaginal artist” Maude – all are brilliantly original creations, and with the three of them colliding in a hall-of-funhouse-mirrors “plot” involving urine-soaked rugs, mistaken identity, marmots in bathtubs, techno-playing German nihilists, naked women in harnesses, John Turturro showing up as a flamboyant Hispanic pederast for no good reason at all, chintzy video porn, White Russians, acid flashbacks, the biggest musical setpiece involving Valkyries and bowling in recent memory, Steve Buscemi suffering a heart attack and dying to no great dramatic purpose, a soundtrack featuring Modest Mussorsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” and Kenny Rogers’ “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In),” Sam Elliott as a cowboy philosopher, and Aimee Mann missing a toe, with no one so much as batting a drooping eyelid at the sheer balderdash of it all – well, gosh, what can you call something like this but genius? Until DePalma suffers a few more box-office disappointments and decides to inflict another masterpiece of pure commercial genocide on us, it looks like the Coens have seized the coveted crown of Hollywood perversity and aren’t looking to give it up very soon. A chilling thought: What do you think they’ll come up with in reaction to this?