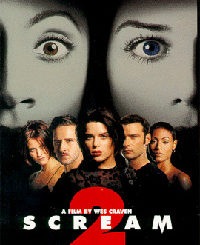

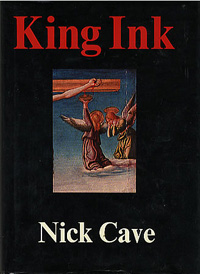

King Ink

King Ink

by Nick Cave

(2.13.61 Books, PO Box 1910, LA, CA 90078)

by William Ham

One of the most heinous aspects of the post-Sgt. Pepper rock-is-art era is the notion of “rock poetry.” Rock lyrics are just poetry set to music, or so they said, in the process subjecting countless generations to come with sensitive singer/songwriter albums, almost everything Pete Townshend’s done since 1969, and college slack-offs the world over writing doctoral theses with titles like “The Use of Byronic Motifs in the Collected Oeuvre of Judas Priest.” Truth is, most rock “poetry” dwindles to doggerel when plucked from its natural habitat and laid out on the page. Anyone who doubts me can pick up a volume of Jim Morrison’s verse sometime.

But there are exceptions. Nick Cave’s field of vision may be restricted to a small, fetid patch of land in the swampy southlands of his mind, home to a rogue’s gallery of Bible-trash, misogynists and murderers, but few can deny that he knows his way around. King Ink, a compendium of lyrics, prose and playlets dating from 1980 to 1988, is a vivid testament to Cave’s progression from crazed Dionysian splatter-poet to classicist Bard of the Bleak. The development is swift and dazzling – the power of early Cave-drawings like “Mr. Clarinet” and “Zoo-Music Girl” is merely hinted at without the full-throttle careen of the band behind them, Cave’s opium visions soon coalesced into rancid tableaux you can almost touch (not that you’d want to), drawing inspiration from the blues, the Bible, and the bog in equal measure. With the last two B-day EPs, The Bad Seed (1982) and especially Mutiny! (1983), Cave broke out of the bleak house that Goth built and into deep-focus cinematic storytelling. “Swampland”‘s acid-Faulkner quicksand scenario is so vivid that he used it as the framing device for his great novel And The Ass Saw The Angel. “Mutiny In Heaven”‘s smack-addled gutter babble rivals Burroughs. From there, it was on to further refinements by way of a solo career, collaborations with the likes of Lydia Lunch, and painstakingly wrought prose and plays, all bearing his own particular stamp. (You’re unlikely to find another telling of the story of Salomé that includes the phrase “Suit yourself, dick breath!”) Typical rock star self-indulgence it isn’t; in his critical essay “HMS Britain 1982,” a swipe at the shallow “New-Super-death Tribe” that Cave partially inspired, he writes “a group that REFLECTS anything other than their own idiosyncratic vision is not worth a pinch and anyway that is enough of that full stop.” As you travel through the darklands of King Ink, with its images of freaks, felons, and fools borne on the sick wind of Nick Cave’s text, the promise in those words comes clear. That he gazes at the void and sees such depth in the darkness makes him one of the few rock stars worth his weight in words.