Gastr del Sol/Roger Miller

Gastr del Sol/Roger Miller

Upgrade and Afterlife/Benevolent Disruptive Ray (Drag City/SST)

by Nik Rainey

Mission of Burma and Squirrel Bait were two of the prime movers of the post-punk indie schism of the ’80s. Though they existed in separate parts of the decade, they held several things in common: a righteously dense, anthemic sound, a passionate cult following that grew even more intense after the fact, and a mercurial lineup that fractured after two great albums. The key members of both bands also turned their backs on the heavy noise they stirred up in favor of quieter, more painterly explorations – infuriating, perhaps, to those fair-weather fans looking for fist-shaking flameouts, but possessed of the subtlety that was hidden under the parent bands’ Richter rumble.

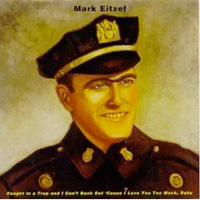

David Grubbs’ journey from teenage velocity boy to avant-guardrail bounding the coarsest of the fine arts is a tale that could be titled Squirrel Bait and Switch. After the Bait wriggled off in different directions in ’86, Grubbs kept the ill faith with Bastro (who were just like Big Black, only smaller and paler), then slipped into an aesthetic supporter to back seminal Texas nutbar Mayo Thompson in approximately the umpteenth version of the Red Krayola. In ’93, he vaulted over the wall of pound, with the magic fingers of Brise-Glace pick-scraper, Jim O’Rourke, there to boost him, and landed safely on the abstract plain of minimalist musical collage where they have remained as Gastr del Sol. The surreal cover photo of Upgrade and Afterlife, their third album, says it all in a glance, which is to say that it says nothing, but evokes impressions that defy rational description. Quiet acoustic guitars give way to a frenzied horn interlude with bleeping electronics lurking in the corner; vocals flit out of the ether, drop a few impressionistic phrases (“Cooked corn in formaldehyde/ popcorn in an airtight jar/ cornflakes under glass/ a second sun was discovered on May 21”), then disappear; all is soothing, all is jarring. At times, their circular scamper brings to mind a drumless, unplugged Slint (the band formed by fellow Squirrels, Brian McMahon and Britt Walford), but the overall effect is unique and wholly their own. Gastr del Sol makes background music that quietly asserts itself into the foreground.

Roger Miller had a very good reason for shirking the oblique cacophony he minted as guitarist and main songwriter for Mission of Burma – it was making him deaf. So instead, he used his talent for non-linear composition and Enoesque sonic variables in a staggering number of projects, from the modern chamber music of Birdsongs of the Mesozoic to the here-come-the-warm-jets-over-Tiger-Mountain pop of No Man. Miller’s crossings have taken him into divergent instrumental solo territories as well – Oh. (Forced Exposure, 1988) was a convincing return to his axe-murderer days and his Maximum Electric Piano performances were justly praised… what’s left? The Benevolent Disruptive Ray, a collection of pieces performed solely on a Steinway, that’s what. Like Gastr’s disc, Ray could easily be mistaken for ambient wallpaper if you’re not paying attention, but is actually quite daunting in its sheets-of-sound intricacy once you unplug your ears and pay attention. Roger’s obviously been listening to lots of John Cage, Cecil Taylor and Sun Ra; the trio of prepared (alligator clips and other objects fastened to the strings) piano improvs are like a more melodic take on Cage’s early-fifties klankwork, certain elements of his technique resemble Taylor’s baby-grand-thrown-down-six-flights-of-stairs approach, and he covers Ra’s “A Call for All Demons” for good measure. With any luck, this album could jumpstart the stuffed corpse of classical music the way Burma hotwired the slightly-better-smelling body of rock, but I think you can guess how likely that is.