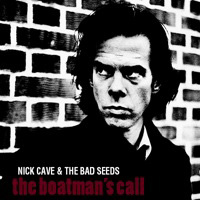

Nick Cave

Nick Cave

The Boatman’s Call (Mute/Reprise)

by Nik Rainey

Almost twenty years after he first yowled into the over-amped abyss of the Birthday Party, it’s good to see that Nick Cave can still find new ways to shock. Last year it was Murder Ballads, a splatter-folk song cycle with willfully perverse touches ranging from a decidedly nontraditional rendition of “Stagger Lee” (“I’d crawl over fifty good pussies just to get to one fat boy’s asshole” – Elizabeth Barrett Browning, right?) to a fourteen-minute, minutely detailed account of a massacre in a tavern (“O’Malley’s Bar”), to the most horrifying touch of all – a duet with Kylie Minogue. It even managed to shock Nick himself – the album he had designed to alienate and appall as many listeners as possible became his best-selling release to date and even garnered him an MTV Europe Video Award nomination alongside the edgy likes of George Michael and Bryan Adams. For a man whose dark tangents and hyper-literate thrusts demanded the safe confines of a cult following, mass acceptance is the kind of thing that would drive him to his most desperate act yet. And so, with The Boatman’s Call, he has performed the only shocking act remaining – an album of straightforward love songs, free of literary obfuscation and with the simple, perfect soul of devotionals.

One could take the cynical tack and presume Cave’s pulling the kind of conciliatory switch-up that, say, Lou Reed did in the mid-seventies by rushing out the love-happy Coney Island Baby to atone for the, ah, somewhat uncommercial Metal Machine Music. But Cave’s about-face here seems more heartfelt and real. Seems our boy Nick has found love (and with whom is none of our business, seeing as we are a serious journal of musical scholarship and not some chintzy tabloid – it’s PJ Harvey! It’s PJ Harvey!… ahem. As I was saying), and with it the oft-wished-for ability to make straightforward, honest statements about it without throwing up an artfully-constructed lead curtain of verbiage to hide them behind. This is the aspect of The Boatman’s Call that ironically renders it a more risky project than even Murder Ballads – some have already sneered at the lack of gallows humor and melodic overkill herein, but my guess is they’re embarrassed. Cave’s love for Bacharachian schmaltz (the most transcendent schmaltz there is) has always been just as strong as his penchant for apocalyptic skreek, but the jaded coolsters that make up too much of his audience always had that bastard irony to clutch close to their chests like a security shroud, thinking that covering “In The Ghetto” and “By The Time I Get To Phoenix” or writing lush originals like “Straight To You” and “Slowly Goes The Night” was, on some level, a hip joke. No fucking way. Nick Cave has thrived far longer than any of his supposed peers in the early-eighties gloom gulag because his fierce passion informs everything he does, and, although he doesn’t raise his voice above a plain croon once on this album, the intensity is enough to wash away every posturer in the pack. And gosh, I can’t seem to find the life preservers.

Anyway, personal vendettas aside, let’s consider the album: It’s obvious that Cave’s spiritual side has been brought to the fore along with his newfound amour, and the very first lines make that explicit: “I don’t believe in an interventionist God,” he sings in a surprisingly humbled mumble, “…but if I did, I would kneel down and ask him/ Not to intervene when it came to you.” With those words, he sets the tone for a suite of songs so single-minded that they’re practically a concept album. The collision of flesh and spirit is, perhaps, Cave’s great theme; the rankest sinner may exist in the same skin as the most exalted saint. Often, these themes manifested themselves in dark, nasty forms: the demonic “Loverman” and the infamously rabid “Hard On For Love” are two prime examples. Here, both the arrangements and the words are pared down: the Bad Seeds’ support is subtle, often to the point of near-nonexistence (you could make a game of it: Where’s Blixa?), and Nick’s lyrics bravely skirt the edge of artless cliché in ways reminiscent of Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away.” This leaves his voice to provide the emotional content, and it’s fair to say that he’s never sung better: never a man possessed of great technical skill, Cave uses the imperfections of his voice with remarkable control, opening up vistas of feeling, and communicating all that needs be said with every waver and crack. He catalogues his lover’s features (“Black Hair,” “Green Eyes,” repeated references to a “heart-shaped face”) and the tiniest moments (like her “big fat cat” meowing love at her) with a quiet awe, almost as if to capture them indelibly before they fade from view forever, and even the most temporary loss is expressed with gorgeous ache (the way he repeats “Last night she took a train to the west” at the end of “Black Hair” is utterly heartbreaking). Cave’s vision of love is far from wine and roses, of course – again and again, he betrays the inescapability of his joy’s decay, undercutting an idyllic moment with the nagging refrain “people just ain’t no good,” and grasping at a greater power against an undertow of ambivalence not so much cynical as mournful. This is probably as close as we’ll ever get to Nick Cave, shorn of bluster and so honest in his self-doubt it’s never cloying: “this sad old fucker with his twinkling cunt,” as he (somewhat bewilderingly) calls himself at the end of The Boatman’s Call, has stripped himself naked and stands courageously in the open, and it puts the armored histrionics and false candor of 99% of contemporary musicmakers to shame. Sneer at it at your peril.