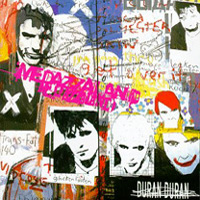

Duran Duran

Duran Duran

Medazzaland (Capitol)

An interview with Nick Rhodes

by Nik Rainey

Okay, okay, I can hear the scoffs echoing through the hollowed halls of the indieground – “Duran Duran? The band my older sister used to swoon over when she was in junior high? You’re doing a feature on those guys? What, was Kajagoogoo unavailable?” And you can just shut up right now. Far from simple nostalgia for MTV 1 A.D., the band that crystallized the term “videogenic” is nosing its way back into the pop consciousness in a big way. Not only are today’s noisemakers beginning to acknowledge the influence of this band (to the point that they’ve finally earned a tribute album [see review on page 14]), but Duran-squared itself, now a three-piece after completing the purge of all members with the surname “Taylor” from the band, is back with their most entertaining album in several years, Medazzaland (Capitol). Astoundingly, they’ve pulled off the trick of making a record that sounds right in step with the late nineties without sacrificing their inherent Duranitude or copping musical trends in a transparent attempt to stay hip. On the eve of Medazzaland‘s release, founding member Nick Rhodes checked in with Lollipop with a few words on the state of the union there in Medazzaland, starting with the obvious question…

Could you explain the album title to me?

Could you explain the album title to me?

Medazzaland first came up when Simon arrived to the studio very late one afternoon, just sort of floating through the doorway. We said, “Wow, what have you taken? Where have you been?” And he said, “I’ve been to the dentist to have some surgery on my jaw and they gave me this sedative called medazzalin. You have to stay awake through the procedure so you can respond to what the dentist is saying, but actually you don’t really know what’s going on, and then at the end of it all you forget completely what had gone on.” He said he felt like he’d lost three hours of his life. He knew it had happened, but he couldn’t remember a thing about it. And we said, “Well, you’re still in Medazzaland,” and that was kind of it, we laughed and thought “What a great word that is!” And how evocative, too – kind of a dreamscape of sorts, only much more frightening, the thought that you could lose three hours of your life and have no idea where they had gone: what were you doing in that time? And then I wrote the voiceover for the track “Medazzaland,” which at that point was only an instrumental, keeping with that theme but taking it a little further into themes of paranoia, not wanting to let go and trust other people. So a trip to the dentist became this metaphor for modern existence (laughs).

As a band so synonymous with a certain time and place, do you find there’s an image problem you have to overcome?

As a band so synonymous with a certain time and place, do you find there’s an image problem you have to overcome?

There’s no doubt about it, if you use imagery that’s that striking, you do become synonymous with it. Certainly in the eighties, there were certain things from the videos that became firmly entrenched in peoples’ minds with Duran Duran, that you have to say, “Wait a minute, that was ten years ago!” I mean, think about the changes you’ve been through in ten years, what you feel about the world right now as compared to what you felt about it then when you were twenty, and you’ll understand. That was very difficult – I think the first time we really conquered that in the nineties was with “Ordinary World,” which sort of captured the moment, the kind of melancholy feeling that was in the air, and the desire to go back to something a little more basic. And this album has moved along, now that the nineties are starting to become a little more defined, this album I think reflects the kind of controlled hysteria and underlying chaos that we’re living in and some of the greater extremes. And also, looking a little bit at the technological side of things and posing a few questions about that. It’s partly right in the present and partly quite a ways in the future, this record is, which is an unusual combination.

It does sound very contemporary without stealing from jungle or drum’n’bass like many other artists have been doing.

Right. The thing is that it’s very easy for us to make a record like this because it’s very honest. I think a lot of other bands out there are searching for a direction, basically being bound to the traditions of rock bands, which I wouldn’t ever accuse Duran Duran of, but they’ve been rock bands for so long and suddenly they’ve discovered stylists and dance music. I think it’s very difficult to change your whole style so late into a career when you’re so firmly entrenched in something else. So it works well for us in that way where it might not work as well for other artists.

Do you remain in touch with the other former members of the band?

Do you remain in touch with the other former members of the band?

Yeah, somewhat. Roger, we see occasionally around London. Andy I haven’t seen in a few years, but obviously he’s still out there, having just done a new Power Station project and all. And obviously, John we talk to – we were quite saddened to lose him, but it was time for him to sort of metamorphose.

Having Warren Cuccurillo in your band has obviously brought out a different dimension in your sound. Not many people can say they’ve played with Frank Zappa, Missing Persons, and Duran Duran. Obviously, there’s a certain versatility there.

Yeah, Warren’s been with us effectively since ’86, but I think The Wedding Album was where we really locked in together. He’s very responsible for bringing in a new writing style for the nineties. He’s extraordinary. I think the things that he’s doing technically with his guitar – not just his playing, which has always been of an unbelievable standard – but his use of certain effects, like these gadgets of his called Jam Mats, with which you can make guitar loops. So in effect you can have three of Warren playing live – he plays and loops himself, then plays another one, then plays on top of that, which creates this amazing wall of sound that is just so far beyond what others are doing with the guitar. He uses the guitar more like a synthesizer, in addition to knowing how to play beautifully on an acoustic. He’s really dynamite.

Have you heard the new Duran Duran tribute album yet?

It’s very diverse, isn’t it? In all honesty, I like some of it, and other ones didn’t work as well for me. But of course, I’m very flattered that the artists would have taken the time to do our songs, not to mentioned stunned by the breadth of musical styles on there, from speed metal to ska! Not much that I would have thought Duran Duran would have inspired in any way, but I’m quite glad that we have because that says something about us. I’m glad that they were all fairly young acts, and I really am pleased at how diverse it all is. Because we’ve always been influenced by a great range of different styles and forms of music, and to see it boomerang back at us like that is kind of interesting.

The Thank You album gives a good indication of what your influences were musically – what about today? What modern artists do you enjoy?

I think by far the most important American artist to come out in many years is Beck. I really think he’s got his fingers on the pulse and I love the records that he’s made. He’s taken American music somewhere different, too – it was getting really stagnant there for a while, but he and the Dust Brothers are doing something very special. European stuff – obviously some of the electronica stuff is really cool. The Chemical Brothers’ album I like, we’ve been listening to the Prodigy for a few years now. It’s its own area, really – I think of it as great music to listen to in the car, really loud. The new Portishead record is quite good – I was a bit concerned, because I loved the first one and I was worried that the new one would sound too similar, but it is a fine record in its own right. I think some of the songs on the new Radiohead album are quite good; the Verve single, “Bittersweet Symphony,” is probably the best record I’ve heard all year so far; and I’m sure there’s plenty more to come this year, actually.

How does the press respond to you guys these days? The British press in particular?

How does the press respond to you guys these days? The British press in particular?

Oh, miserable. I don’t think we even bother sending our records to the British press anymore. It’s reached Monty Python proportions by this point – they don’t even listen to the music in England anyway, they just try and find little indie bands they can posit for a while until they get a hit, at which point they decide they don’t like ’em anymore. They cannot be taken seriously, the British press, not just by me, either. Many others have fallen victim to their insincerity. But we don’t really even talk to them, and it’s a comfort to me knowing that they’ll have to go and buy the record if they want to slag it. (laughs)

How about the American press?

Well, they’re certainly not nearly as silly as the British, but I find they treat us with a certain extremity of opinion – you’ll find those that are absolutely fanatical about the record, and some who can’t stand it and wish we weren’t around anymore. But I’d rather provoke some kind of reaction – I think the worst kind of review you get is when they say, “Well, it’s all right,” that sort of passive indifference. The last album didn’t get reviewed all that well, but the one before it did. So we’ll see. I don’t pay a great deal of attention to it, but obviously, when you have something that you’ve worked on for a long time, you’d like it to be well received. I do what I do to please myself, of course, but also to entertain people. It’d be a pretty miserable existence if I just made records that I myself liked but nobody else did. If we were the only audience for our records, that denies it a certain validity. We’d like our records to get a fair hearing in the media, radio and television particularly, so people can hear it and decide for themselves if they like it. People can get very wrapped up in the minutiae of the presentation and completely miss the question of, “Well, is it a good song?” And it’s easy to let the press dictate what you like and dislike. I think of the film Mars Attacks! as an example. Critics just slagged it, it got terrible reviews, but I went to see it and the audience stood up and applauded it at the end! And yet that did poorly because of the press, whereas Independence Day did extremely well even though it was a piece of commercial crap. It took itself so seriously. What I hope people will get from us is a sense of kitsch, pop art almost, that’s been missing from music for a while. It’s all tongue-in-cheek and that’s the way it should be.