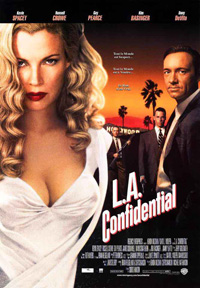

L.A. Confidential

L.A. Confidential

With Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, Kevin Spacey, Kim Basinger, Danny DeVito, James Cromwell

Written by Brian Helgeland and Curtis Hanson, from the novel by James Ellroy

Directed by Curtis Hanson

by William Ham

In the hands of dozens of post-war pulp novelists, the City of Angels has become the City of Angles. As in: everybody’s got one, is being played for one, or being cut by one. For a desert town, Los Angeles is fertile ground for duplicity, a hotbed of labyrinthine deception, and an overheated hatchery for hardboiled clichés. Raymond Chandler may have forged the seminal vision of the L.A. underworld – all black eyes and white heat – but it’s James Ellroy who shot it through with a creeping grey that only makes the white shadier and the noir darker.

It’s a brilliantly fevered, deeply haunted vision Ellroy proffers, nihilistically entangled and rat-a-tat blunt – Céline as dimestore fictionalist. But that same rabid perception and staccato prose style (as if he has so much story to tell he can hardly be bothered to finish his sentences) have heretofore kept his books from being the high-commodity silver-screen items that, say, Elmore Leonard’s have. The only other Ellroy adaptation extant, 1987’s Cop, took his crazed novel Blood on the Moon and flattened it into a standard exploitation flick as unremarkable as its title, with James Woods’ typically off-the-beaten-wall performance (which Ellroy reportedly hated) the sole remaining hint of ambiguity. With that as precedent, few would have expected much better from L.A. Confidential. But lest we forget, Hollywood is a place of strange alchemy – how else to explain how the guy who wrote The Postman, the director of Bad Influence (I would mention Losin’ It but I’m not that cruel), two relatively unknown Australian actors and an actress widely considered washed-up (don’t hit me, Alec) could take the text of a seemingly unfilmable (some say unreadable) novel and turn it into one of the most thrilling, layered pieces of dark cine-`mericana in a long, long time?

The answer is simple (which makes it that much more miraculous): balance. A good mainstream picture requires strong, archetypal characters, and the three that anchor this film would appear to fit the bill perfectly. Bud White (Russell Crowe) is a hard-nosed, brutal cop who saves his worst beatdowns for wife-beaters and has no qualms about infringing on people’s personal rights in the name of justice. Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) is a square-jawed, by-the-book officer hungry for advancement and intolerant of his colleagues’ mistreatment of the rules. And Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) is a slick, star-crazy narc who picks up a little side income serving as technical advisor for a cheesy TV cop show and setting up celebrity busts for a low-rent proto-Enquirer rag called Hush-Hush (represented by Danny DeVito at his delightfully sleazy best). Sounds like the kind of characters who’ve appeared, with slight variations, in cop dramas from Dragnet to NYPD Blue, but details and shadings begin accumulating almost as soon as those broad strokes are slathered onto the screen.

It doesn’t take much to imagine that these three, very different men will wind up sharing common ground before long, or that deceit, corruption, and more double-crosses than a cockeyed Catholic schoolkid’s field of vision are soon to pile up in fetid, sunbaked strata, as will stacks of dead bodies – this is, after all, a crime movie, and such cogs and gears are built into the machinery. What you may not expect (but should, if the diminished expectations we’ve grown to accept from our entertainment system hadn’t pummeled it out of us – exactly when did “no-brainer” become a recommendation?) is how rich the movie is. It’s got one of the most intricate plots in recent movie memory (which I won’t even try to recount here), and like any good film noir, it’s thick with atmosphere – of the supporting characters, Kim Basinger (as a Veronica Lake-looking hooker and obscure object of desire) and James Cromwell (well-suited for his role, having already embodied the moral/ethical split as Charles Keating in The People vs. Larry Flynt and, um, spending a lot of time around pigs in Babe) have garnered justly-deserved praise for their pivotal turns, but perhaps the most important supporting role in the film is the title character itself, clad in impeccable period dress but keeping its presence character-actor subtle. Here and there, like with any of the humans that inhabit it, you catch glimpses of L.A.’s back story, its inner life: note the billboard exhorting people to join the LAPD – “A Good Job in a Good Town” – and you’ll realize how soon this city would lose its ability to trumpet such modest, forthright statements without cynicism or irony. This foreshadowing is what gives L.A. Confidential its power (and allowed critics to make their tiresome Chinatown comparisons, which, to be fair, don’t quite wash – no one could make an L.A. story so damp with doom without having his wife murdered by filthy hippies first, and I don’t think Hanson wants to be an artist that badly) and makes its division of individual morals almost sadly quaint – flash-forward four decades and who’s the first man who comes to mind when you think of the LAPD? Why, Mark Fuhrman – the public face of an Exley masking the brutality of a Bud White and the fame-hungry soul of a Vincennes, good cop/bad cop/indifferent cop all in one easy-to-hate package. Like the greatest period pictures before it, L.A. Confidential captures its moment with the memory of what’s been lost and the horrible knowledge of how much more there is to lose. All that while keeping the clenched-jaw detective-movie faith. Quite an accomplishment.

It doesn’t take much to imagine that these three, very different men will wind up sharing common ground before long, or that deceit, corruption, and more double-crosses than a cockeyed Catholic schoolkid’s field of vision are soon to pile up in fetid, sunbaked strata, as will stacks of dead bodies – this is, after all, a crime movie, and such cogs and gears are built into the machinery. What you may not expect (but should, if the diminished expectations we’ve grown to accept from our entertainment system hadn’t pummeled it out of us – exactly when did “no-brainer” become a recommendation?) is how rich the movie is. It’s got one of the most intricate plots in recent movie memory (which I won’t even try to recount here), and like any good film noir, it’s thick with atmosphere – of the supporting characters, Kim Basinger (as a Veronica Lake-looking hooker and obscure object of desire) and James Cromwell (well-suited for his role, having already embodied the moral/ethical split as Charles Keating in The People vs. Larry Flynt and, um, spending a lot of time around pigs in Babe) have garnered justly-deserved praise for their pivotal turns, but perhaps the most important supporting role in the film is the title character itself, clad in impeccable period dress but keeping its presence character-actor subtle. Here and there, like with any of the humans that inhabit it, you catch glimpses of L.A.’s back story, its inner life: note the billboard exhorting people to join the LAPD – “A Good Job in a Good Town” – and you’ll realize how soon this city would lose its ability to trumpet such modest, forthright statements without cynicism or irony. This foreshadowing is what gives L.A. Confidential its power (and allowed critics to make their tiresome Chinatown comparisons, which, to be fair, don’t quite wash – no one could make an L.A. story so damp with doom without having his wife murdered by filthy hippies first, and I don’t think Hanson wants to be an artist that badly) and makes its division of individual morals almost sadly quaint – flash-forward four decades and who’s the first man who comes to mind when you think of the LAPD? Why, Mark Fuhrman – the public face of an Exley masking the brutality of a Bud White and the fame-hungry soul of a Vincennes, good cop/bad cop/indifferent cop all in one easy-to-hate package. Like the greatest period pictures before it, L.A. Confidential captures its moment with the memory of what’s been lost and the horrible knowledge of how much more there is to lose. All that while keeping the clenched-jaw detective-movie faith. Quite an accomplishment.