AmeriMart

AmeriMart

Part One

by Todd Bredan Fahey

illustrations by Tom Powers

I have to write this down, if for no other reason than to look back on it when I’m feeling right again – so I can know for certain that I was not going mad; and if I am, well, I leave this as some vile sort of record to my posterity. Whatever the hell this is (it’s so new and strange and personal that I don’t see how it could have a name), but whatever it turns out to be (and that will probably be nothing at all, or nothing more serious or lasting than a fever or the onset of Spring)… whatever the hell it is, it belongs in this moldered journal. Just a spin through this Register of Shame makes me hunger for the tang of a speeding bullet: How is it that a man consigns his whole being and purpose in the Food Chain to the vagaries of the more conniving sex? (I suspect that the marketing wizard who termed them the “Fairer” was probably blackmailed, or was at least kept in a way that someone in my strata could never comprehend.) These mysteries are making me sleep like shit at night. And taxes are due next week. God, is there no respite for the fool?

And now this fitfulness. The one proud constant in my life has always been an unflagging capacity for a full night’s sleep. True, uninterrupted sleep: Through all four stages. So what if I send two dermatologists on luxury cruises every summer, or that in less than two decades I’ve graduated from three cycles worth of shots to boost my natural histamine tolerance, and that now my current allergist claims even ground Polar Zero would throw my dermal layer into an eruption of bleeding hives at least seven weeks out of the year? I could blot it all out every night with a dependable, eight-hour coma.

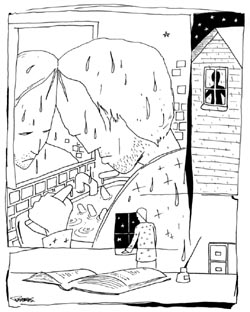

But now everything’s different. It feels like what my rehab counselor used to call a “dry-drunk,” though I don’t ever recall being sensitive to one then. I fall asleep quickly enough – fifteen to twenty minutes – but I can tell something’s not right. I never actually get to where I need to be. It’s like the breaths one takes after a hard crying jag: those shallow, fruitless gasps that satisfy like a Twinkie to the hypoglycemic. There are no dreams; the only release from this shrouded agony comes with the morning alarm, which I have set such that I awaken to the sage babbling of National Public Radio. This is where the real hell begins.

I haven’t told anyone. I can afford a shrink, but he probably wouldn’t commit me if I came begging and drooling on my knees. Glynnis is pining again for a more exciting man, someone who will take her to a bungalow on some black sand beach and fill her full of native rum and fuck her ruthlessly each sunset out on the screen porch. We both know it’s really about money – she hasn’t been interested in sex for at least two years – but she says she will be the moment that bronze stallion trots by and tells her to throw a leg up.

Maybe her threats have something to do with this weird morning fusion. I’m not sure of anything anymore.

Pat Carmichael glanced at his watch and shuddered. Five a.m. had come hard lately. Each morning for the past two weeks, he found himself dousing his face with frigid tap water to reduce the pouches that had begun filling with some sort of viscera underneath his eyes and chin. He stowed his journal again into the back of the file cabinet he and Glynnis used for tax records – actually, that he used: Glynnis hadn’t brought in an income since the birth of their second child, eleven years ago, and it was the one piece of furniture he knew she would never think to rearrange. He walked into the bathroom and stared at himself in the mirror, feeling as if he weighed considerably more than his scale weight of one-hundred ninety-two pounds. Friends used to remark that he carried it well, but now he felt like the Michelin Man.

The sun would not be up for more than an hour, but he needed the extra time to shake off the residue left on his deteriorating psyche by the morning’s NPR broadcast. And the pixie-dust was abnormally profane this morning: all over America, the old and the rationally enfeebled were falling victim to a new and particularly vicious marketing scam, known in the schemers’ own parlance as “Family Buying Clubs.” He had been too groggy to catch the particulars, but he trusted Cokie Roberts when she warned him to beware: that record numbers of fools were being separated from their money in past weeks. And he knew his own household was not immune. In fact, they were pitifully easy prey.

Since the advent of the Home Shopping Channel, Glynnis Carmichael had been its most enduring booster. He couldn’t begin to chronicle the scrolling list of debits made to the Carmichael Visa card in the name of “HSC America, Inc.” since 1987; to do so would bring on a weeping psoriasis from which, in his state of mental and physical fragility, he knew he might never recover. Their lighted curio cabinet in the corner of the living room, which she had ordered through the TV, quartered every wretched little Hummel figurine; three Bosson’s heads crowned the portal of each of the fourteen rooms of the Carmichael home, with the Dickens Collection occupying a wall of its own in the study, over his own impotent exceptions. The grinning jigaboo, clad in some loud sarong, which he had found lurking over his two children upon their return for Thanksgiving last year – as Glynnis read to them from the latest (bargain-rate, she assured), gold-leaf Politically Correct volume of the World Book Encyclopedia – he felt, was finally over the top. He managed a rare, albeit meager, victory on that count, for the next time he looked, the Soul-Captain was gone, apparently returned for The Chef, which now hung over the refrigerator.

He poured himself a triple-shot of espresso from their new brass steamer unit… the one with the built-in programmable clock, then walked silently into the shaving area in the master bedroom, where he opened the medicine cabinet and fumbled for his trusty bottle of antihistamines, tossing back two tablets with the full contents of the acrid sludge. This was his morning routine, and nothing he did this morning would rouse Glynnis from her prescribed Halcion stupor. His habit of walking quietly was an acquired remnant, learnt by age nine. His mother, they assumed at the time, had suffered a marked propensity toward migraine headaches; in hindsight, he realized she simply was never fond of children, not even of her own stalk.

And soon after the birth of their son, it was clear that Glynnis, too, could scarcely tolerate the scents and the racket emitted from the newborn, though she insisted on having another. “You don’t have just one,” she had said at the time; but by the time they had turned eight and ten, she found even a bare facsimile of coexistence to be unthinkable.

The doctors initially called it a mono-polar disturbance, a delayed post-partum reaction, they felt – probably hormonal in nature – but that it should pass. After five years of hellish domestic turmoil, they downgraded the estimation to “acute narcissism, with a near-phobic aversion to her own children,” and issued Pat Carmichael three options:

1) try out a good boarding school, with the hope that Glynnis could at least approximate a nurturing posture over the vacation breaks;

2) divorce Glynnis and take sole custody of the children – a move, they assured, which would go unchallenged in court; or

3) give up the children to a family more conducive to their natural demands. And since Glynnis was never dangerous to the children, nor to herself, none of the psychiatrists would agree to have her committed. Not one.

Pat Carmichael returned to the Church that month, after a ten-year apostasy, and long were the hours of his confession. Monsignor Lafferty felt him so wronged and blameless that he sent him away without penance, offering, lamely, only that, “It may have been prudent for Glynnis to have remained more like our Blessed Virgin.”

It was an airtight fix, his friends all admitted. And this morning, not even the pre-dawn roar of his ink-black Ferrari Dino Boxer could puncture the vaporlock.

Leslie Dunlap knew she had the routine down cold by the fourth walk-through, and even her new manager had to admit to himself that there could be no more ideal spokesmodel for the AmeriMart concept on this special evening than Leslie Dunlap. She was a coke-slut like all the rest, but she had class – a forgotten quality in the AmeriMart operation of late. She wore it in her dress: the plunging blouses and thigh-high skirts from Victoria’s Secret, and in the faint brush of green over her almond eyes, and the burnt sienna she applied over the thick curves of her lips. If she hadn’t come with protection during that first interview, Jack Reynolds might have been afforded the privilege of testing the warranty on the new mylar, stain-proof Ever-Wear carpet that had just been installed in his office. But Ms. Dunlap never gave him the chance.

Leslie Dunlap knew she had the routine down cold by the fourth walk-through, and even her new manager had to admit to himself that there could be no more ideal spokesmodel for the AmeriMart concept on this special evening than Leslie Dunlap. She was a coke-slut like all the rest, but she had class – a forgotten quality in the AmeriMart operation of late. She wore it in her dress: the plunging blouses and thigh-high skirts from Victoria’s Secret, and in the faint brush of green over her almond eyes, and the burnt sienna she applied over the thick curves of her lips. If she hadn’t come with protection during that first interview, Jack Reynolds might have been afforded the privilege of testing the warranty on the new mylar, stain-proof Ever-Wear carpet that had just been installed in his office. But Ms. Dunlap never gave him the chance.

He knew right away that she would hurt him if he pulled anything aggressive; the freeze-dried look in her eyes was a more than adequate tip-off, even if he hadn’t noticed the bald-headed spade in the front seat of the new Lexus that sat idling in the first stall of the temporary AmeriMart lot. In the other trollops, he had seen an easy once-off each evening; in Leslie Dunlap, he saw a treasure trawler.

Jack Reynolds had been operating AmeriMart, in its various titular incarnations, since 1982, with nary a felony conviction to his proud Irish name. It was the perfect scam, so long as he kept reasonably mobile; and in recent years, he had even gotten cocky about that, staying in Salt Lake City for a solid eight months before feeling strange pangs of guilt at the prospect of toying with the local quarry forever, with impunity.

The sites changed as caution dictated, but the raison d’etre remained a cruel constant. Before moving into a new locale, one with at least two pro-circuit golf courses, Reynolds would scour the local thrifts and S&Ls; for recently-defunct businesses carrying satisfactory ratings from the areas’ Better Business Bureaus and Chambers of Commerce. Against a deep tan from his portable solarium, in his lightly starched Brooks Brothers’ Sea Island cotton tab collar shirt and custom suits by Joseph Abboud, Reynolds knew he looked like pressed-solid funds to 80% of the despondent VPs at Your Local Thrift. Those who could not be prevailed upon outright by superior tailoring would be summarily disarmed by an evening of chic dining with an ocean-front/mountain-top/canyon-rim view.

He would work with only younger executives from the commercial real estate divisions, preferably those under thirty-five. The young, childless chap with a vehicle worth over half his yearly salary usually got the nod. These were the cads who should be found guilty, Reynolds reasoned; if not for perpetuating his own particular shell game, then doubtless a dozen others. At the suggestion of drinks, the banker would follow Mr. Reynolds to a carefully-selected restaurant, one of whose staff would tolerate eccentric behavior with a knowing smile, and where Reynolds would lay down the irresistible proposition:

“This must be kept incredibly quiet,” Reynolds would say, despite himself. “I’m compromising so much here.”

“No, no,” the VP replies, waving his hands over the white linen tablecloth. “Hmm-mmm. Treat this conversation like I were your own surgeon.”

“Well, I’m glad to hear it,” Reynolds nods, visibly relieved. “I’m gonna cut to the chase: in ten weeks, we begin filming the biggest action adventure in the history of Hollywood. And we want to do it right here. Right goddamn here!”

The banker’s eyes dilate, then flutter.

“Last time we moved in, to Daytona Beach, we bought up a whole street’s worth of houses, right on the sand… leveled them all just for the view. It’s big, it’s huge….” Suddenly, Reynolds reaches into the inside pocket of his suit and produces a small glass vial. “I keep thinking I’ll get bored of the whole thing. But I never do. It’s so goddamn exciting – the stars, the filming. The bimbos,” he chuckles. “And now that this stuff’s so cheap,” he says, tapping out what the banker estimates to be nearly a gram onto a porcelain bread dish. “Oh,” Reynolds withdraws suddenly, and with all apparent sincerity, “I hope I haven’t offended you.”

“No, no, not at all, Mr. Reynolds. I understand completely.”

“Good,” he shouts. “I’m gonna need an aggressive broker like yourself to look out for our interests. Now let’s kick-start the ol’ faculties, shall we? It’s gonna be a long one.”

This particular pitch, over braised quail and baby asparagus tips at the Eagle’s Nest, with its needle-top view of Scottsdale, Arizona, landed Jack Reynolds a three-month, nothing-due lease at the vacant administrative office of AmeriMart, a defunct dimestore/cosmetic chain that once covered the greater Phoenix city limit. In this new desert oasis, he found the pleasure of no less than fifteen exquisitely sculpted courses for his new Gary Player clubs; Hobie Cat racing on man-made lakes in the afternoons; and in one final, giddy stroke of fortune, he found Phoenix to be some sort of natural roost to the bonniest, most sophisticated and uninhibited call-girls he had ever laid lap on.

Over the course of a decade, Jack Reynolds had become a skilled draftsman of dynamic classified ads, the spin of which never failed to draw the most delicious, vapid young coeds and would-be skin-film actresses. He was especially proud of his latest blurb, which promised:

XXX-itement

$Do you turn heads$

$Can you make a preacher stutter$

$Do men always say “Yes!” to you$

I need one Elegant Beauty immediately for

high-dollar, fast-paced marketing venture.

Call: Mr. Jack, 555-8752

This was the ad that had brought Leslie Dunlap out of the lazy poolside sun and into the front door of the reopened and newly refurbished headquarters of AmeriMart in whom he found a perfect partner: erotic, guileful, conscienceless. Theirs was an instant, almost organic, symbiosis, a consummate harmony in the imperfect order of things. The predators were roused to hunger, and the time had come to bring on the host of fools – to separate them from their money.

Glynnis Carmichael was roused to consciousness around 11:30 – as she was every day but Sunday, when noon or even 1:00 might see her still in a state of blissful slumber – by the sound of the mail truck, followed by a distinctive clacking of the postal carrier as he walked toward the slot hidden in the Carmichaels’ front door. They had tried a mailbox on the street for a couple years, but when Glynnis’s legs began bothering her, not long after the birth of their daughter, she and Pat both agreed to move the drop indoors. There was also, to her mind, the question of safety – a concern which Pat had routinely dismissed, but which had caused her nothing short of insoluble anxiety. Since she retrieved the mail the second it left the carrier’s fingers, her compulsion could very well have been monitored by any of the scores of molesters whom, she reasoned, might sit lurking in theirs and every other decent cul-de-sac, waiting for just such a helpless creature as Glynnis Carmichael to seek the one bit random solace in the otherwise stultifyingly dull existence of the practically childless American homemaker.

And so, on this late-morning, all that was necessary to accept delivery of the just over a score of envelopes which came pouring from out of the slit in the door was for Glynnis to roll out of bed and make what would appear to any impartial witness to be one long, protoplasmic push toward the front of the house. The weight was a bother, no doubt, but ever since Oprah had lost that first 40 (which Glynnis was secretly glad she could never really keep off), she had lost all heart. And since Patrick had become practically impotent anyway, she found no compelling reason to torture herself. She ate according to the dictates of her own metabolism, and she ate often.

Taking the opportunity to sit and catch her breath, Glynnis Carmichael folded her nearly gangrenous legs beneath her and sifted through the newly fallen pile of envelopes until she found the one she was looking for: a small yellow card, which declared her an “Instant Winner,” in the sum of either a 25-inch television set, a 35mm camera, or $25 in cash. The card had come from AmeriMart, and she knew to anticipate it from the four or five phone calls she had received in recent days from the same enterprise. It was a short-time promotion, the woman had insisted, and could she register the Carmichaels for an exclusive one-hour tour through their new showroom?

“Sure,” Glynnis had said.

“Wonderful,” the woman answered. “You’re going to love our prices.”

How could Pat refuse? She had gotten some terrific deals through The Home Shopping Channel, but much of the merchandise had since entered prematurely into various states of decomposition, and she never seemed to have the strength to ask the manufacturers to make good on their collective guarantee. AmeriMart was different. Their “Factory-direct” merchandise, the card assured, came with the “Full Manufacturer’s Warranty.” All this at prices “below-wholesale.”

She chuckled to herself, and struck a pose for the next two hours at the kitchen table, sipping from a Diet Pepsi while laconically consuming a tin of 24 Mrs. Fields cookies – the full-fudge numbers, dipped in white chocolate – whilst compiling a list of the many household improvements necessary for to someday transform the spacious-but-simple Carmichael home into the denizen of gala entertainment she had always envisioned for their rapidly passing and nearly wasted lives.

At four o’clock, she phoned her husband at the dealership. “Hi, honey,” she giggled. “Guess what we’re doing after work? … Be serious,” she coughed. “No, no. We’re touring a new showroom in Phoenix. I got a card today; it says we’ve already won a guaranteed gift. So I thought as long as we’re there, we’d get you that laser printer you keep whining about. Uhhm… I don’t know. I guess I could call them back,” she grumbled.

Glynnis hung up on her husband and dialed the number listed on the yellow card, and heard the woman’s familiar voice. “If my husband and I come to your showroom,” she wondered with rare caution, “and we like what we see, how much is it to join? Oh,” she laughed, embarrassed even to have asked, “we can handle that. Yes, this is Glynnis Carmichael. Uh-huh. 5:30? We’ll be there.”

She hung up and redialed her husband’s number. “Goddamnit, Pat, you made me feel like an idiot: it’s $15.99! You pay twice that for a haircut! Now pick me up at 5:00, and don’t be late.”

to be continued…