Generation X, No Artificial Additives

Generation X, No Artificial Additives

by Jamie Kiffel

illustrations by Rich Mackin

“You can take your damn pill and shove it,” Alice said primly, straightening the pleats on her blue pinafore. “I prefer to take the problem to the face, and face what happens to my head.” – Lodi Majie

“I’ve gotta go to the shrink, refill my Prozac prescription,” an acquaintance on my dorm hall said, flipping aside a long, dyed-red shank of hair. She was the third girl that week I’d heard talk about her shrink and her prescription drugs. She was so hip, so beautiful, but as friendly as we’d become in four years, I knew I’d never be let inside her real circle of confidantes… I wasn’t part of the anti-depressant set.

It seemed ubiquitous – the really in-deep hipsters flaunted their prescription drugs and treatment programs like sexual score cards, measures of brazenness and desirability. If you were really screwed up in the head, you were worthy of admiration and even desperate lust from these dyed and drugged dryads, who only wanted to compare self-destruction and rub into each other’s bruises. Late at night, the pierced and the tattooed girls typed their most personal stories of depression and emotional shredding across the campus to one another, using electronic bulletin boards that only members had passwords to use. Wiltingly thin, pale and hollow-eyed, these exquisitely deranged and uprooted creatures tapped away their sadnesses to one another until the bleary hours when they’d sneak off to each other’s rooms and burrow into their Q-Tip sized dorm beds together, locked in late gray morning embraces. They flirted by showing off their scars and prescription drugs, and fell in love with one another’s vices.

That, for me, was the identity of Wellesley’s true Generation Xers – an underbelly of drug users, altered girls with complicated eyes. I couldn’t help strangely envying the complexity of pain that they cultivated and I lacked, keeping me from ever being one of the people whose eyes they wanted to use as microphones. I was a pure snow drift beside their suicide-sliced arms and ratty books of bleak poetry spewing vitriol at a patrilineal society. After all, I wasn’t a life-torn, misunderstood shadowy shiverer with kohl-black eyes. I was just a brainy girl who would graduate with a great degree, and go on to a fabulous job in media like any plain and simple adult. End of story. Or so I thought.

I was about to get complicated. But it wouldn’t take Prozac to do it.

Long before graduation, I started mailing out several resumes a day. I didn’t think about the fact that no one was responding until I got home and found myself sitting in my childhood room, staring at the walls. The resumes had been mailed into The Void, and there was little more that I could do than keep mailing futile cover letters to enormous corporations who apparently used them as wallpaper or kindling. Lucky enough to live off my parents, I sat suddenly steeped in sadness and hopeless immobility, realizing like slow, dull reality that nothing but someone else’s money separated me from life on the street. I was a complete dependent, a leech, unable to command my own life. And the more weekdays that I filled with writing seemingly futile cover letters, the less powerful I felt.

But then suddenly, as if life shoved me a handful of amphetamines, my career life was jammed with a massive head-rush. In the course of one day, I landed an interview at a local newspaper and was hired – as managing editor of the entire paper. It was time to get off my soft bed pillow, put away my resume, and pound myself across the pavement.

The dim, wide office I stepped into was piled high with papers, folders, phone numbers and diskettes shoved in every direction. This dark space, sectioned off from the sunny front of the office with a partition wall that didn’t quite reach the ceiling, was all my territory. I looked blankly at the three phones, five desks, three computers, and three old scanners scattered around me.

“So… could you describe my job a little bit?” I asked my boss, an aging beauty queen with bleached Marilyn Monroe hair, gold faux jewels, an enormous diamond ring and tight lycra pants with a hole right in the crotch seam that showed every time she sat.

“You just go in there and do it,” she grinned through a sloppy lipsticked mouth. I now noticed my “In” box piled two feet high with papers and a “To Be Looked at More Closely” box beside it, piled almost as high. My illusions of decisively making petite copy marks on editorial exploded loudly inside my chest.

“Jamie,” shrilly squawked a stout, older woman with thin, reddish hair and a face that resembled Winston Churchill. She hustled over to me, seized my arm and pulled me aside. “Don’t let her take advantage of you,” she hissed, motioning toward Greta. I tried to smile and giggle a little, politely. “She’s done it to every other editor and she’ll do it to you. But don’t let her,” the woman, Nell, insisted.

My heart jamming blood into me faster than I could breathe to circulate it, I thrust myself among the giant hill of papers and started to sift. “Jamie,” Nell yowled an interruption, coming around the corner from her bright desk into my dim quarters. “Listen, what are you doing for the education section?”

Education section? There was one?

“We promised this college a full feature before you got here. They’re taking out a full page ad, so it’s a disgrace if they don’t get it. They’ll never renew the contract if we don’t give them this. And after all the times they’ve advertised…”

“Um… sure, Nell,” I agreed.

“Thanks, Jamie!” she exclaimed sweetly, almost with relief. “That’ll be great.”

I would soon find out that there was a reason why Nell sold the most advertisements at the paper. She’d manipulated every editor before me into doing whatever would serve her best. But I wasn’t yet at the point where I could say no to a 60-something year old woman. I would learn quickly.

In the meantime, I needed some help figuring out the rest of the paper. “Um, Greta…” I started, coming toward the publisher’s desk.

“Sssshhhhh! I am constantly being interrupted!” Greta exploded, throwing her pen down with no warning at all. “I… I’m going to lose my mind! I’m just so buzzed, I’m having an attack! If no one, if no one leaves me alone, I’ll never get anything done.”

“I’m sorry…” But Greta’s hand was on her head and she was already shoving her papers aside like there was no use trying to ever look at them again, since I’d completely ruined everything.

“Jamie, Jamie, listen… You must wait. I am so busy right now, I… I’m over my head! Can’t you see this? Look, just look at this mess.” She pushed the enormous pile of haphazard papers covering her desk, and a few small figurines thudded to the floor. “I don’t know how a sane person can be expected to find a thing in this,” she went on. “I have no idea what’s in here, my driver’s license could be in here, my car keys for all I know. Oh, look, here’s an extremely important invitation and it’s just thrown down where no one will ever find it! It’s… it’s not normal. Look, Jamie, make an appointment. You choose the time, any time you like, Darling. Write it into my book and you and I can have a whole hour or however long you need to talk about whatever it is that you want to talk about. But not now. Not now. Is that okay? Not now.”

“Jamie, Jamie, listen… You must wait. I am so busy right now, I… I’m over my head! Can’t you see this? Look, just look at this mess.” She pushed the enormous pile of haphazard papers covering her desk, and a few small figurines thudded to the floor. “I don’t know how a sane person can be expected to find a thing in this,” she went on. “I have no idea what’s in here, my driver’s license could be in here, my car keys for all I know. Oh, look, here’s an extremely important invitation and it’s just thrown down where no one will ever find it! It’s… it’s not normal. Look, Jamie, make an appointment. You choose the time, any time you like, Darling. Write it into my book and you and I can have a whole hour or however long you need to talk about whatever it is that you want to talk about. But not now. Not now. Is that okay? Not now.”

As my vision darkened, I realized that nothing in my life had prepared me for this. But it was too late for that. It was time to live off my wits, and find out if printer’s ink really did run in my veins.

And then the test arrived.

Each month, Greta threw me bigger and bigger curveballs – assigning me entire feature sections days before the paper was due, re-editing pages she’d already approved and claiming that she’d never seen them before, or even telling me to delete Nell’s pieces, and then blaming me for doing such a terrible thing. But the queen of all the experiences came several months into the job, just hours before the printer’s scheduled pick-up time.

My art director, Danny, and I knew that we were cutting it close… We’d been working from 9 am until midnight every night for a week, and now were in the last hallucinatory moments of an all-nighter. Just then, the phone rang. It was Greta. “I’ll be late today, Darling, but you know what to do with the paper, right?” she gushed. “You’re wonderful. You’ll have no problem. Oh, you’re wonderful.” Then a pause, as her conscience pricked her for a fleeting moment. “I certainly hope that you and Daniel weren’t there all night. Tell me you weren’t there all night,” she said, suddenly concerned and accusatory at once. But before I replied, “But oh Darling, I forgot to mention to John, our printer, that we won’t be needing him anymore – I found someone cheaper and switched to them. So the old one mustn’t come. Would you please call him and tell him not to come? Thank you so much, Darling. Goodbye.” Click.

What? She’d left me alone in the office as the sacrificial lamb awaiting the claws of a terrifying, weasel-like printer, a classic

misogynist with longish, thinning hair and eyes like prongs. And worst of all, I knew things could only get worse before they got better.

I dialed his number.

“That bitch,” he said, in a freezingly crisp monotone. “That fucking bitch. My driver already left, Jamie. You have to give him the paper. There is no option.”

” I’m sorry, but we can’t,” I said.

“You can’t? You can’t? That fucking hag!” Click. Both printer and pick-up man were on their way.

I continued to work on the paper in horrified anticipation of their arrival. Danny’s concentration was starting to fizz away with the sleepless hours, and I could almost see his nerves starting to fray. Then our copier ran out of toner. Our computer printer ran out of ink. The computer froze and lost some of our work. And then the new printer, a polite woman in a crisp suit and expectations of actually picking up a paper and leaving within a few minutes, arrived.

“Okay, are we ready?” she musically chirped.

The layout editor moved his chair to the corner, twitched, and began to rock and stare at the wall. I had to finish the paper myself, and I only knew the most rudimentary commands to the layout program.

Just then, the front door burst open. I took a breath and stepped out to face John.

“Where is she?” he demanded.

“She isn’t here,” I asserted.

“You’re lying. Get that bitch out here now. Greta? Greta!”

“She isn’t here, John,” I insisted, refusing to move from my spot as he raced around the office, peering under desks for the woman.

“Well, get her on the phone,” he snapped, his mouth quivering with anger.

I had the number. I could have called her. But dammit, this was enough! I would not be their pawn, played between them like a bruised buffer. So I flatly refused.

“What? What do you mean, ‘no’?” he demanded. “You won’t call her? Ha? Ha? Well, let’s see if you’ll call her once I start doing this!” And he began to pull antique paintings off the walls of the office. “Let’s see what you think now!” he shouted, his eyes popping out as he yanked painting after painting off the wall. The new printer shivered in the corner, and whimpered as she noticed the art director sitting there shivering already. I ran behind my partition, pausing to whisper to an intern that everything would be just fine, and called the police.

All this time, the only other person present was Nell, who decided to use this moment to get back at Greta for every time she’d ever cut out one of her articles, or paid her late (which was often). “You’re absolutely right to steal those,” she squawked to John. “Serves Greta right!”

With quivering hands, I jammed the receiver to my ear and whispered to the police. Just then, Nell burst around the corner and found me. “What are you doing? Why are you calling the police? Why are you calling the police?” she exclaimed. Suddenly, she was on the edge of tears, realizing that I might reveal that she was abetting the thief. “I’m calling my husband!” she cried. Her husband was a lawyer. She thought she was scaring me. She wasn’t.

The police arrived just as the printer left. I told him which car I thought was John’s, though – it was still parked up the block. More police zoomed in, sirens blaring holy horror, closed in and surrounded the car. Suddenly, I heard Nell screeching louder than ever. “YOU TOLD THE POLICE TO GO TO MY CAR?” she screamed at me. “That’s my car! Oh my god! What a disgrace! I’m calling my husband!” The old woman’s tears scared me more than anything else.

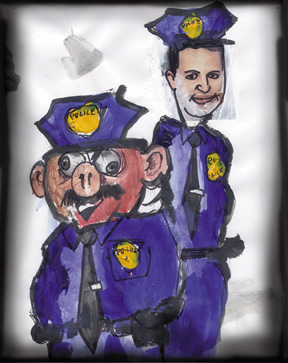

Just then, the police walked in – a young, thin, attractive cop and a pudgy, slightly older one. “Who’s in charge?” the young one demanded, frowning hard.

“I am,” I asserted, and offered my hand to shake his.

“Who’s in charge here?” he said again as if he didn’t see me.

“I am,” I said sternly. He glowered at me and my hand, hanging there in space.

“Are you pressing charges?” he snapped.

“I… I don’t have that authority,” I said.

“Well, why did you call us here?” he shouted, beginning a lecture on playing around with the law. I explained that I’d felt unsafe and needed protection. Now the other cop started complimenting a cover story I’d just written about a new female commissioner.

“She’ll never last, they’ll eat her alive,” the young cop sneered. The pudgy one smiled at me and said he reads the paper every morning while eating his donut. I wanted to throw a few at both of them. They finally left, unable to press charges. Just after they pulled away, the publisher waltzed in, her hair freshly bleached, her make-up thick and bright, and her fur coat heavy and wide.

“What’s been happening? Did the paper go to print?” she asked breezily, removing her thickly gold-rimmed sunglasses and unclipping her large gold earrings.

“No,” I growled.

“No,” I growled.

“NO?” she shrieked. “Jamie, what are you doing here? That paper MUST go to print, no matter WHAT! Get it out, I don’t care WHAT shape it’s in! PLEASE! You’ll RUIN us! You’ll put us out of business! Do you understand what you’re doing at all?”

I glowered at her.

“What is it, Darling?” she asked, in a rare moment of perceptiveness. With all possible calm, I recounted the last few hours.

“Why, if he wanted the paintings, he should have just asked for them!” she laughed. “I would have given them to him!”

I ended up emailing the missing remainder of the paper to the new printer. The old printer visited the police station, briefly, then was released when Greta said she wouldn’t press charges. The paintings and statues eventually came back some time later, but different – scratched, dented, broken. Personally, so was I. My damages were all inside, settled behind my bones and in my eyes. But strangely, there were improvements. My cracked double joints gave me massive flexibility, and through my smashed retinas I suddenly was able to see untruth, lies, and double-talk clearly. My fear had been so exercised that it turned tough and thick, and surrounded my soft innards so that only a truly massive spear of abuse could bruise them. I’d developed the war wounds and callouses of a leader.

I freely admit that without the sudden jolt of that first job, I might have continued to sit and stare blearily at the walls of my room, wondering how able I am. Instead, I’ve since gone on to edit a national magazine, and can clearly picture myself one day becoming an editor-in-chief. Beating my way through this trial with only my wits to help me has convinced me that I have the ability and the right to forge my own way in society.

Yet still, many Gen-Xers aren’t empowered with the concept that we can invent, that we can do anything we darn well please. In fact, the drugs that so many of us feed on are, I feel, a way to step out of and avoid the harshness needed to mature and toughen us into commanders of ourselves and our world. After all, if you’re healing from a sickness, you can’t be expected to function at full-force and confront the things in life that really are worth the complication.

I certainly accept that there are cases where prescription drugs are truly necessary to help a person function within society. But I am also convinced that many who take these drugs are simply deadening the fodder in their heads that is necessary for accomplishing the most difficult trials in life. For whatever reason, we are believing that offbeat thoughts and ideas breed uncomfortable feelings, and should be extracted via pills. But those very impulses, slightly out of sync with normal reality, are the only things that can change it. In order to bring the outside world up to temperature with our creative insides, we must abrase the world through our skin, and that doesn’t always feel good. And so I incite you all, 20-somethings, to let the slightly disjointed, uncertain, edgy feelings inside you start seeping out. These are not barbed abnormalities that should be dulled so they won’t scratch the world we were born into. They are your sharp tools for sculpting a new society.

I incite everyone who feels powerless within my generation to shatter the structures that you see as comfortable directors – whether they be academic rigors that lead you to no more end than some more time to think about what you want to do, or a parent’s rules, or a job that was designed simply to give someone a job – and start making your own way. The old structures are training wheels. They are rusty. You can create the restaurant that serves 30,000 people a week. You can build the company that turns out the next multi-million dollar product. You can hire a corporation. And you don’t have to be a certain age, and you don’t have to have a leader. Just open your eyes and ears and burst forth. The world is afraid you’ll try. So tell them to take their damn pills and shove them. Unleashed, your mind can explode the structure and invent a whole new system.