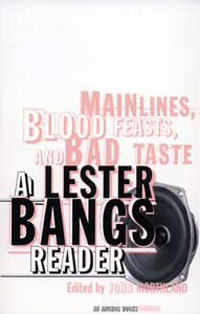

Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste

Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste

A Lester Bangs Reader

Edited by John Morthland (Anchor Books)

by Brian Varney

Not so much a companion piece to the first, Greil Marcus-edited Lester Bangs reader, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, as a completely separate entity (note the subtitle “A Lester Bangs Reader”), this nevertheless does seem to set out to correct many of the fine first compilation’s many glaring omissions, quite a few of which were brought to light in Jim Derogatis’s excellent Lester bio, Let It Blurt. The most obvious of these was Lester’s love for early heavy metal pioneers such as Black Sabbath and Grand Funk, a love whose existence was not even hinted at by the first collection (thanks in no small part to Marcus’s hatred of the genre). These bands obviously meant a lot to Lester and are mentioned many a time within the pages of this collection, both in passing and as the subject of pieces such as the brilliant and courageous “Bring Your Mother to the Gas Chamber!,” which must’ve been one of the few pieces in major rock magazines circa 1972 offering praise for Black Sabbath.

Thanks to the legacy created by these and other pieces, Lester Bangs is considered one of the godfathers of rockwriting, one of the first and best to essay the form. And while there’s no doubting that Lester was a very good writer whose love of music was very passionate, he was also, like a large majority of rock writers, too much of a word person for his own good. While this was understandable, his being a writer and all, it’s nevertheless a failing. As a writer myself, I too can enjoy good lyrics, but they’re not as important as Lester or a lot of other rock writers make them out to be. I look at it like this: The musical portion of a song is like a steak, and the lyrics are a bottle of steak sauce. While the two can and often do complement each other wonderfully, the scales of importance are heavily tipped when the two are divorced. After all, steak without the sauce is still STEAK and tastes just fine on its own. Who, on the other hand, is gonna drink steak sauce alone?

However, such quibbles are to be expected when reading another’s opinions and should not hinder your enjoyment of the writing itself, which is the true focus of this anthology. If you read Lester, most of what you’ll read is as much about Lester himself as the purported subject of the piece. This sort of solipsism, to use a word he loved, is very common in much of the rockwriting that has passed through the door which he so recklessly smashed. That much of what he influenced is not worth the paper upon which it’s printed is not his fault, but it’s nevertheless important to mention that his work was viewed and continues to be viewed as highly influential.

Lester was a truly great writer, one of very few in this or any other sub-segment of the writing racket. Having stumbled upon the rockwrite thing more or less by accident, Lester always viewed himself first and foremost as a “real” writer. I use quotation marks not to mock but merely to highlight what I see as a fallacy in this not-uncommon school of thought. The purpose at the heart of any genuine attempt to write is to expose some deeper, greater truth, which can be done regardless of the form or subject matter of said writing. In Lester’s case, this struggle for expression was conducted, for the majority of his career, under the guise of writing about rock and roll. Like many rockwriters who view themselves as something more, Lester struggled to escape the rockwrite tag and make a name for himself as a “real” writer, i.e. a novelist. The irony here is that his best rock writing was far more “real” than his attempts at fiction which, judging by the excerpts of his unpublished novels Drug Punk and All My Friends are Hermits included here, were clunky, full of unnecessary faux-Beat affectation, and, above all, not very good, lacking the racing heart and rushing wind that gave breath and blood to the best of his rockwriting.

(www.anchorbooks.com)