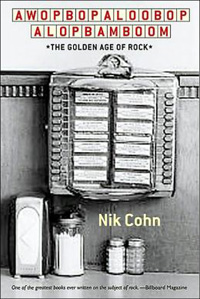

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom

The Golden Age of Rock

by Nik Cohn (Da Capo Press)

by Nik Rainey

To many, Nik Cohn’s biggest claim to fame (other than astrally projecting into the future and psychically leeching the spelling of my first name) is that he authored the story upon which Saturday Night Fever was based. But years before, he was one of a small, select tribe of scribes who pretty much created rock journalism as we know it. (Assign credit or blame at your discretion.) Like the rest of his august company, Cohn was an inveterate overachiever, a prodigious chronicler who channeled the energy of rock ‘n’ roll into print with a style that belied both his age (he began contributing to the Observer at eighteen) and the allegedly sub-intellectual gestalt of the music itself. In 1968, Cohn retreated to a rented house on the west coast of Ireland and, in seven weeks, composed what may well be the first-ever book of rock criticism, Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom. The timing was perfect – rock was only then starting to calcify into self-conscious Art, and acid-penned idealists like Cohn still held out the dim hope that the infected parts could yet be lopped off without killing the patient. Deep down, he probably knew better, but remember that, for all the social foment and excessadelia of ’68, it was still the year that Elvis regained feeling in his pelvis. The fire had not yet been banked.

After twenty years out of print, Awopbop… still holds up as a reminder of the true imperatives of rock ‘n’ roll, before commerce and significance reared their ugly heads, a thrust that Cohn sums up in one word that should be two: “Highschool.” The odd thing about the early rock writers is that, for all their impressive erudition, they looked disdainfully upon the sophistication that set in during the music’s adolescence, and Cohn was no different. In his eyes, rock ‘n’ roll should’ve never left the hop; once the marketing departments began contriving explosions and teen idols felt the need to make statements, something pure and primal was forever lost. Again and again, he returns to the central dilemma: how can talented songwriters live up to their need to progress without abandoning the teenyboppers who, after all, are the ones who actually buy their damn records? (There’s something tragically naïve in that question; Cohn apparently didn’t yet see that adolescence itself was forever changing along with the music, and didn’t quite catch the sad irony in a twenty-one-year-old bemoaning innocence lost.) Then again, that’s what makes this book so crucial, despite being almost thirty years out of date and riddled with factual errors (by the author’s own admission) – it’s a heavily subjective snapshot of a time and a place when the Great Teen Dream, while gasping for breath in an oppressive atmosphere of superstar pretension, still had a little life left in it.