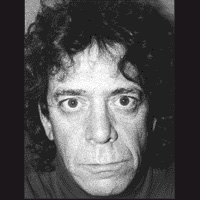

Lou Reed

Lou Reed

At the Photographic Resource Center

An interview with Lou Reed

by William Ham

Velvet on Kodachrome

A little word of advice to anyone who wishes to hunker down in the warm, dirty trenches of rock journalism: Make sure your words aren’t too bitter or poorly spiced, ’cause chances are you’ll end up noshing on ’em before you’re through. Case in point: last issue, in my review of Victor Bockris’ Transformer: The Lou Reed Story, I concluded with the statement, “I’ll never want to hang out with the man after reading (this book).” It seemed a pretty safe assertion at the time – after all, I’m a friggin’ zine writer, an unwashed squatter in the sub-basement of the Fourth Estate. Bass players in local bands with half a split 7″ to their credit feel they’re doing me a favor if they deign to grunt at me. How likely is it that I, a dried-up sprig of parsley in the rock-media food chain, would ever have the opportunity to breathe the same air as the capo di tutti capi of punk (and post-punk and glam-rock and meth-core and smack-pop and…)? I’d have a better chance of booking Nico on a comeback tour with Johnny Thunders, Sid Vicious, and Keith Moon as her backing band, right?

Well, imagine my surprise when I discovered I’d been chosen, as one of a small, handpicked group of correspondents, to represent the cream of the local media at the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University for an afternoon press conference and reception with musician, poet and visual artist Lou Reed, whose five photographs serve as the centerpiece of the PRC’s Extended Play: Between Rock and an Art Space, an exhibition of paintings, photos, and multi-media work by musicians. And why don’t you keep imagining that, because, in truth, that’s not quite how it happened. I wasn’t exactly hand-picked. Strictly speaking, I wasn’t even invited. Amelia Copeland at Paramour magazine was (either because of the artistic quality of her publication or because the PRC wanted to make sure the clitoral-piercing demographic was amply covered), and she kindly faxed me her invite. To perforate my self-important bubble further, I had to explain to the woman to whom I RSVP’d that Lollipop is a music magazine and not, as her uncomprehending silence seemed to suggest, a trade publication for members of the confectionery industry. If humility were non-dairy creamer, I could service the breakrooms of half the middle-managers in Boston already. But lo, my adventures in journalistic ineptitude had not even begun.

WHITE LIGHT/WHITE KNUCKLES

WHITE LIGHT/WHITE KNUCKLES

Actually, there was a perfectly good reason why few music writers were summoned to the PRC that unconscionably humid Wednesday. The invitation read, “Mr. Reed has expressed his desire that questions should focus on his relationship to the visual arts, his photography, and his participation in the… exhibition.” In other words,don’t talk about anything interesting. Not that I have anything against the visual arts – heck, I’ve been to museums at least, oh, three times in my life – it’s just that: a) I don’t know f-stop from a-hole about the techniques of photographic art, b) no matter how arrestingly composed these as-yet unseen pictures may be, the only reason they’re being shown in expensive frames on a museum wall instead of in a dusty family album alongside blurry snaps taken at Six Flags is that a legendary rock star took them, and c) the only thing more bile-inducing than the dull-witted musings of rock fans is the nasal, Ur-pretentious mewling of overeducated, overprivileged art enthusiasts. Normally, the thought of spending any amount of time with the kind of people who toss out phrases like “affirmative utilization of negative space” and “proximate motifs of earthy transcendentalism” would send me fleeing for sanctuary at the nearest vocational school, but I was willing to put up with a lot for a chance to forage for significance with the Rock and Roll Animal.

So off I went to the PRC with my notebook, a borrowed tape recorder, and a case of nerves worse than Bobcat Goldthwait after a double shot of crank. I hadn’t the slightest idea what to ask, so I brought my copy of Bockris’ book along in the vain hope of hitting on some relevant information (“So, Lou, how did allegedly bitch-slapping David Bowie in a crowded restaurant influence your use of available light?”). When I arrived at the Center, a place about two-thirds the size of my apartment, my fears were not exactly assuaged by the warmth of the assembled crowd welcoming a fellow scribe into their midst. I may as well have been a practitioner of the custodial arts judging by the bemused glances I received. Once or twice, I attempted to break the ice with a friendly smile, but only half my mouth would comply. Most of the dozen or so people there appeared to know each other, so I resigned myself to standing awkwardly to one side while they bantered amongst themselves about their self-released CDs, multi-media video projects, and most amusing hangovers. Fuck, man, it’s high school with a slightly better vocabulary.

After about ten minutes of this, I hit upon a brilliant way to bide my time before Reed arrived: I’ll look at the pictures! As it happened, there were two exhibits running simultaneously that month –Extended Play and The Velvet Years, a collection of photos from Warhol’s Factory from 1965-67, including more than a few of the young Lou Reed looking cool, sullen, and quietly confident all at once. The stark simplicity of Steven Shore’s photos left me more moved and impressed than most of the rock star art on display, some of which showed definite talent (like John Cohen’s pictures of folk and blues musicians in their natural habitat), some of which was either self-indulgent or silly. I had to stifle a laugh twice – first at Kim Gordon and Daisy von Furth’s contribution, a closet with some of their X-Girl clothing line inside (“Ooh, Riot Gap,” I thought), then at the sight of some of Willie Alexander’s paint-notebook-and-newsprint collages. The works themselves were fine; I just couldn’t help wondering if some Steve Sesnick-type might not hound Lou’s pictures out of the exhibit and put Willie’s works in his place. (I say, that’s an in-joke, son.) As for Lou’s pictures, the ostensible reason we were all there in the first place… I dunno. They’re nice. Other than a grainy, somewhat unnerving self-portrait, they looked like the works of a world traveller with a pretty good eye for offbeat architecture. There’s a blurry shot of a bridge in Stockholm, a confined-looking street in Venice, a glass tower at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and one of those strange-looking buildings the Japanese like to construct ’cause that’s what they do. What can I say about them? I check my yellowed, curling piece of fax paper again.

“…he uses the characteristics of the medium… to speak about vision and disorientation. In contrast to his songs, which speak about disorientation, Lou’s photographs actually create a sense of visual alienation.”

Yeah. That’s what I was going to say.

HERE HE COMES NOW

HERE HE COMES NOW

At this point, I had calmed myself a little by writing snide, superior comments in my notebook (on Patti Smith’s childlike/childish drawings: “Warhol died for somebody’s sins, but not hers”) and silently imagining a day in the life of a particularly smug-looking individual who was examining each picture oh-so-deeply (“I’ll finish up here, work on my master’s thesis, `Existentialism and Hair Loss,’ for a couple of hours, catch part of that ten-hour Indonesian art film at the Brattle, brood, add some strips to that papier-maché sculpture of my superego, go to the bar, have a few drinks, practice my European smoking technique, pick up a humanities major, take her back to the loft, sodomize her, and get to sleep by three.”). I turned the corner to gaze at Shore’s photos a while longer and listen to the Velvets music playing on the loudspeaker, and…

…wound up staring right into the eyes of Lou Reed as he entered, flanked by a film crew and the executive director of the PRC. All at once I was reminded of a scene from the teen-suicide flick Permanent Record, when the good-looking-corpse-to-be and his best friend bluff their way into a recording studio and Reed comes out, gives them a curt “Howzitgoin,” and leaves the two of them moistening their flannel with delight. Mark this down – the only moment in my life when I willingly identified with Keanu Reeves. I sweated, stammered to myself, and nearly geek-walked into a wall. (Reed must have taken one look at me and thought, “What’s David Byrne doing here?”) He adjourned to a separate room for a private interview with some Boston Globe hack, while I… well, I went off into the reception area and guzzled three glasses of Chardonnay (in a moderate, early-afternoon way, of course). Within minutes, I was relaxed enough to initiate a conversation with a gentleman who I discovered was Jon Garelick from the Boston Phoenix. Now, I can rarely count on my own personality to ingratiate myself with those of greater stature than I, so I did what I find works much better – flatter the person with my knowledge/appreciation of their work. “Oh, wow,” I said, “I really like your writing! I thought that Patti Smith tour diary you did last year was just great!”

His smile faded. “Uh, that wasn’t me. That was Al Giordiano.”

“Oh… Great article, though, wasn’t it?”

GROWING EMBARRASSED IN PUBLIC

I wish I could tell you all about the press conference and lard it with lengthy, verbatim quotes from Chairman Reed, but I can’t for two reasons. First, he spoke so fucking softly that nothing came out on tape but my own labored breathing, and second, I was staring so hard at him, I didn’t take any notes. I couldn’t help but draw a clear distinction between the brutal, vitriolic Reed of popular legend and the frail, shy-looking guy sitting in front of me. He’s certainly showing his age (55), but doesn’t come off in person like the ghoul that peers out of some of his less flattering pictures. Nor does he radiate the aloof, magnetic aura of a man who has spent the majority of his life in the public eye. What I saw was a man who could use a good meal and a little shut-eye.

What I recall from the thirty-minute Q-and-A session was Lou paying homage to Factory house photographer Billy Linich, aka Billy Name (most famous for the black-on-black cover of White Light/White Heat) and singling out Vernon Reid’s and Laurie Anderson’s pieces as his personal favorites. The latter should come as no surprise, since he’s been trading both conceptual strategies and bodily fluids with the Vaselined performance artist for several years, but he also happens to be correct – “A Light In August,” her 1974 book which lists items stolen or destroyed from her loft that year alternating with Xeroxes of Albrecht Dürer’s Melancholia, with different items highlighted in red, is a beautiful example of how to be funny, sad, angry and moving while using the fewest parts. And speaking of minimalism, our first exchange of the day was a sterling example of the form. Without the nerve to plunge in with one of my heavier questions, I thought I’d test the waters with a simple opening wedge that would assuredly lead to a long discourse on the gestation, birth, and development of Lou Reed, shutterbug:

“Have you been doing this long?”

Guests of honor at open-casket funerals have regarded me more expressively. “Few years,” he mumbled. If you listen closely to the tape at that moment, you can hear my journalistic confidence hitting the floor. (That wasn’t the only thing that ended up kissing the parquet that afternoon, but we’ll get to that later.) I took the hint – I shut up, left the balance of the questioning to the professionals, and just gazed into my hero’s red-rimmed eyes, mesmerized, searching, searching for…

What? What exactly am I trying to find here? Look, it should be pretty clear by now that I couldn’t care less about art. And, to be frank, I’m guessing that very few of the people there that day, or indeed, few of those who paid their three bucks to get in to this exhibition, are taking any kind of subjective view of the work here displayed. What they/we/I want is a vicarious brush with fame and we’ll lie, beg, borrow, or take a low-paying job writing for a self-important little music rag that no one reads to get it. And in the contact bridge game that is our culture, fame trumps everything. Why do you think Lou Reed is still so vital? Even his staunchest fans spend much of their time slagging the man, virtually no one thinks he’ll ever come close to the heights the Velvets scaled thirty years ago, he’s used up the ensuing years cannibalizing his legend when not simply trashing it… but it doesn’t matter. As long as he’s got the shades, the leather jacket, and the all-black t-shirt/jeans ensemble to go with it, he’ll never need to do anything important ever again. The image is enough. It’s bigger than all of us, including him. Which is such a shame on so many levels that I feel like severing all my ties to music fandom, hawking my entire collection of scratchy vinyl and CDs in cracked jewel cases, and giving all of this up to lead a productive, illusion-free life. Because I do happen to think that Reed is more than just the living embodiment of downtown decadence. And I do believe that he’s still got a lot to offer if we’d only give him the chance.

Unfortunately, that’s an impossibility. It’s hard to make art that speaks for the rest of us when you are no longer one of us, which is why those Velvets records are still so strong today and why nothing Reed has done or will do since will ever resonate quite so strongly. Because he’s not one of us. He’s both larger than life and lower than dirt, exalted and denounced for some of the right reasons and many of the wrong ones. He fascinates because he sought to raise three-chord rock ‘n’ roll, the populist art form of our time, to the level of literature, a very solitary art form. Imagine a packed club of drunken revelers screaming the words of “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” and you’ll get an idea of how irreconcilable the two worlds are. He’s legendary because he opened up that sea of possibilities; he’s tragic because he must spend the rest of his life struggling to harmonize the demands of rock fame (where personality reigns supreme) and creativity (where anonymous observation is necessary for clarity of perception). I envy the man deeply but wouldn’t walk a day in his shoes for a million dollars. What a living hell people like him must live – attempting to make good, honest work while being surrounded by mewling sycophants who think they’re owed something because of it. I’m beginning to understand why so many celebrities self-destruct, and why I should be ashamed for my tiny contribution to the cult of personality, for adding my brick to the bunker where they isolate themselves.

I got so lost in my reverie that I hardly noticed the press conference wind down and the crowd dissipate. Reed stands up, quietly thanks us, and heads for the corridor festooned with thirty-year-old pictures of himself and his friends for a little one-on-one time with anyone who wants to stay. Knowing their place, few take the bait. I, like a good mewling sycophant, tag along at my hero’s feet. I’ll be damned if I’m gonna let Lou Reed shut me out without saying more than two words to me. I’m a big fan. I have all his albums, even the crappy ones. He owes me.

MAGIC AND LOSS

(OF MUSCLE CONTROL)

And yes, I’m happy to say that I got what I was after. Lou Reed did end up talking to me, and I may even have secured myself a small footnote in rock-journalist history in the bargain. But there’s always a catch when you grab the monkey’s paw, so naturally I had to embarrass myself like a maladroit schmuck to get my wish.

About a dozen of us – me, Lou, his friend with the camcorder, Garelick, and a crew from the local newsmag show Chronicle (led by a guy I later discovered was Clint Conley, ex-bassist/ songwriter for Boston post-punk legends Mission of Burma – two icons in one room, how cool is that?) – stuffed ourselves into the narrow hall where Shore’s pictures hung. Conley coaxed some remembrances from Reed about some of the pictures, and Reed kindly obliged, flexing a little of his deadpan wit as he did. (My favorite moment was when he looked at the gorgeous picture of the then-stunning Nico. “Aw, what can I say about this?” he said, pausing just long enough to prime us for some sentimental, regret-tinged anecdote, then deflated the moment with a perfectly-timed, straight-faced rejoinder: “That’s what she looked like.”) I stood at the periphery, biding my time, shifted my weight a little impatiently – and dropped my fucking tape recorder on the floor. My tape shot across the hall and my batteries followed as if to distance themselves from this nervous jerk who’s spending his day playing journalist. Mortified, I bent down to retrieve the rebelling tools of my would-be trade, devising the best, most expedient route to the nearest technical institute so I can start my own gun repair shop in under eighteen months and leave this childish writing lark to those with better educations and tighter grips, when a familiar voice piped up. “Hey, are you okay?”

I looked up and again locked eyes with Lou. Only this time, there was nothing condescending or dismissive in them, only genuine concern and even sympathy. I was floored. (Granted, as I was still doubled over, I hadn’t far to go.)

“Uh, yeah, Lou. Sorry.” I choked out one of my patented forced laughs. “You know how us journalists are.”

“Boy, I know what that’s like,” he said. “The same thing happened to me when I interviewed President Havel of Czechoslovakia. The damn tape recorder jammed and I got so flustered trying to get it started again. It was very hard.”

You read it here, folks – the guy who spent five minutes of a live album ranting at a club owner about “those journalists! Those fucking journalists! Why do you let those assholes in here?,” the self-styled bane of the rock press himself, actually showing sympathy to one of the quill-wielding pricks. And meaning it. Somewhere Lester Bangs was slapping his forehead in awe.

The ice (but fortunately not the recorder) broken, we chatted briefly about the difference between the straightforward language of his songs and the abstract nature of the visual arts, he autographed my notebook with my own pen, shook my hand (because he was so nice, I’ll refrain from speculating about the incredible limpness of his grip), and turned to field a long, convoluted question from an arty chick along the lines of “how do you think your status as a celebrity informs the work you do, you know, in the grand epistemological sense?” I don’t remember how he responded, but I’ll never forget how he turned to me afterwards and mouthed the question back at me with a mischievous grin. Who’da thunk uncooperative tape recorders could be such an effective bonding tool?

As Lou began to pack up and leave for an autograph session at Tower Records, my moment of glory gave way to a moment of clarity. I finally realized why he was there, not as Lou Reed, rock idol, but as Lou Reed, amateur photographer. And with it came the point of this whole exhibition, the thing that gives even the most dilettantish work of these musicians their significance. To see these people doing something other than the work they’re most famous for, something that they might not have the greatest aptitude for, is to see these celebrities in a new, unaccustomed role – as human beings. Most of us could have done the same kind of stuff that they did there, and maybe even done it better. The only thing separating them from us is name recognition. Fame has its advantages and its detriments, but in the final analysis, the luminary isn’t so far from you and me after all. Of course, it’s hardly likely that you or I would warrant a lengthy, florid piece of prose in a monthly publication, although my adventures in gravity did get me mentioned in Jon Garelick’s piece on the event in the following week’s Phoenix (I’ll remember you wrote that one, my friend), and there’s probably not much point in my writing this piece since the exhibition will be long gone by the time this sees print, but what the hell, I had to tell someone. I mean, Lou Reed touched my pen. (Good thing I’m not one of those yellow journalists he so abhors – just two more letters at the end of that last sentence and I’d really have a story.)