Boogie Nights

Boogie Nights

With Mark Wahlberg, Burt Reynolds, Julianne Moore, Heather Graham, John C. Reilly, and William H. Macy

Written and Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

by William Ham

Is there no slippery region of the American underbelly that hasn’t been given the full Hollywood tracking-shots-and-title-cards-and-nothing-under-two-and-a-half-hours-please treatment? You take a gander at the movie biz’ track record and you can almost appreciate what the elected arbiters of our nation’s morality (some of whom, it should be remembered, used to be actors themselves before embracing the conservative tenets of government – a little like kicking smack by taking up rhino tranquilizers, it seems to me) mean when they rail against the dearth of wholesome American values in our cinema; the only happy families in American film are the perverse, non-nuclear ones, like the mob, roaming bands of nihilistic young adults forming bonds over their shared belief in nothing, or that weird psychosexual thing Batman has going on with his, ahem, “ward.” Real families, on the other hand, are riddled with incest, adultery, a mixture of complexes both Oedipal and Electral, and a lack of eating at the table unless there’s a long-simmering revelation to bring to a nice, seething boil. The lawmakers of our land can bellyache all they like about Tinseltown’s participation/ringleadership in the demise of family values (we’re only a couple of years away from a major election, so you’d better get reaccustomed to that phrase now), but we as moviegoers know the truth – the sick stuff’s a hell of a lot more fun to watch. How long did that Leave It to Beaver movie last in the theaters, anyway?

It isn’t lost on Paul Thomas Anderson, a director too young to remember much of the era he covers in his second feature, Boogie Nights, that his picture is, in fact, full of family values and harkens back to a simpler time just like the pols keep trying to do – nothing is simpler than hedonism without fear of consequence, no better way to hold the family together than to have Mom and Bro and Sis fuck one another while Dad directs the action, no time less sullied by doubt, a moral compass, or a functioning intellect than the 1970s, that long victory party for a generation which didn’t yet realize that it hadn’t won a thing. Only in the ’70s could a man like Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) speak in all seriousness about raising pornography to the level of great art; only then could a sweet-natured, dull-witted kid like Eddie Adams, né (I was gonna say “cum,” but that’s far too easy a shot – d’oh!) Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg), dream of the warm embrace of fame (not notoriety) with only a nice smile, an idealistic attitude, and a thirteen-inch schwanzstücker as Dame Fortune’s bait; only then could a black man dress in a cowboy suit outside of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. It was the last moment in time when anything could be taken at face value – before long, cynicism and irony crept into the culture, a chill fell over interpersonal relationships as harsh as the textures of the videotaped porn that took film’s place, and sickness, addiction, and death put the final kibosh on unconscientious fun. No wonder Boogie Nights, like the films it most resembles – Altman’s Nashville, Scorsese’s Goodfellas, and even Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction – utilizes the decade’s trappings as canvas for a cinematic action painting, a messy statement about the American dream and how it helps to be spiritually asleep to go after it.

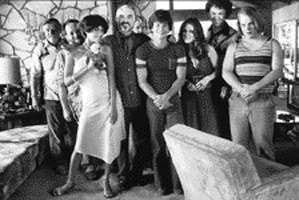

Surely, you know the story by now, the indelibly human characters Anderson created to carry it, and the overriding “family” metaphor that runs throughout (an aspect that Anderson plays up a trifle too much – the early scenes with Joanna Gleason as Diggler’s shrewish mother are a little overplayed, and Julianne Moore, a wonderful actress, has to work very hard to keep the maternal yearning her porn-queen character Amber Waves displaces onto Diggler from growing too mawkish), and no doubt you’ve heard volumes about the film’s last scene, an homage to Scorsese’s Raging Bull that breaks the unspoken rule about these kinds of movies, a rule that, cleverly, Anderson upholds until the very last minute. (And before you ask, no, it’s not real.) But provocative subject matter, a campy setting and campier casting do not a classic make – hell, Burt Reynolds can tell you that himself after his disastrous “comeback” turn in Striptease. Boogie Nights happens to be one of those rare films where every element is well-orchestrated and every passage bears fruit. Casting-wise, he hit the jackpot – Wahlberg and Reynolds are as perfect in their roles as everyone says they are, but let us not discount the less flashy work of John C. Reilly as Diggler’s constant second, er, banana, Reed Rothchild, who gets a perfect comic rhythm going with Wahlberg from their first meeting (“How much do you bench-press? Let’s say it at the same time…”) through their mutual rise and fall (the recording studio sequence is painfully hilarious). Heather Graham shows great form (in about three definitions of the term) as the always-skating Rollergirl, a potent combo of fresh-faced naïvete, sensuality, and pent-up fury. And the always-fab William H. Macy, as “Little” Bill, Horner’s assistant director, is just as fine here as he was in Fargo, maintaining a role as the “family”‘s walking moral dilemma with little more than his expressively pained face as guide. (He also plays a major role in a humiliatingly comic subplot involving his character’s wife, played by bona-fide porn starlet Nina Hartley.)

Surely, you know the story by now, the indelibly human characters Anderson created to carry it, and the overriding “family” metaphor that runs throughout (an aspect that Anderson plays up a trifle too much – the early scenes with Joanna Gleason as Diggler’s shrewish mother are a little overplayed, and Julianne Moore, a wonderful actress, has to work very hard to keep the maternal yearning her porn-queen character Amber Waves displaces onto Diggler from growing too mawkish), and no doubt you’ve heard volumes about the film’s last scene, an homage to Scorsese’s Raging Bull that breaks the unspoken rule about these kinds of movies, a rule that, cleverly, Anderson upholds until the very last minute. (And before you ask, no, it’s not real.) But provocative subject matter, a campy setting and campier casting do not a classic make – hell, Burt Reynolds can tell you that himself after his disastrous “comeback” turn in Striptease. Boogie Nights happens to be one of those rare films where every element is well-orchestrated and every passage bears fruit. Casting-wise, he hit the jackpot – Wahlberg and Reynolds are as perfect in their roles as everyone says they are, but let us not discount the less flashy work of John C. Reilly as Diggler’s constant second, er, banana, Reed Rothchild, who gets a perfect comic rhythm going with Wahlberg from their first meeting (“How much do you bench-press? Let’s say it at the same time…”) through their mutual rise and fall (the recording studio sequence is painfully hilarious). Heather Graham shows great form (in about three definitions of the term) as the always-skating Rollergirl, a potent combo of fresh-faced naïvete, sensuality, and pent-up fury. And the always-fab William H. Macy, as “Little” Bill, Horner’s assistant director, is just as fine here as he was in Fargo, maintaining a role as the “family”‘s walking moral dilemma with little more than his expressively pained face as guide. (He also plays a major role in a humiliatingly comic subplot involving his character’s wife, played by bona-fide porn starlet Nina Hartley.)

Little Bill’s abrupt exit from the story, at the appropriately pivotal setting of a New Year’s Eve party welcoming the ’80s, reflects the lack of anchorage that follows these characters into the Reagan decade. Film is soon to be replaced by videotape, ruining Horner’s dreams of art-for-fuck’s-sake; the performers spiral out of control on coke and ego; and dreams go careening downhill quickly, leading to a number of brilliantly-orchestrated setpieces. One follows several major characters, estranged from each other, as their lives become a (quite literal) bloody mess within a block of each other simultaneously; the other, a hypnotic scene of comic horror that tops Tarantino and Scorsese at their own game, is a botched coke scam involving guns, fireworks, Alfred Molina in bikini underwear, Night Ranger and Rick Springfield – the stuff of which nightmares are made, you will agree. By the time Anderson echoes his first shot with his last – a long track through Horner’s home where the intertwined fates of the major characters are brought to a cautiously optimistic but still open-ended conclusion – you realize what throws Boogie Nights beyond its subject matter and setting into the realm of all truly great movies. Anderson loves each and every one of his characters for all their flaws and failings, letting them put themselves through the wringer but always welcoming them home. Sounds like family values to me.