Cul de Sac

Cul de Sac

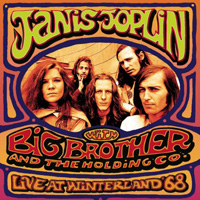

The Epiphany of Glenn Jones (Thirsty Ear)

An interview with John Fahey

by Nik Rainey

Redawn of the Iconoclast

John Fahey’s a hard man to get ahold of. I mean that several ways: As a musician, Fahey, now 58, is best-known for introducing a new, finger-picked style of acoustic guitar playing in the sixties, releasing literally dozens of records of instrumental compositions capped with cryptic, surreal titles and liner notes that turned him into the toast of the coffeehouse hippie. An entire genre of acoustic music took direct inspiration from his signature style, and for years (especially his troubled down time in the 1980s, when he contracted Epstein-Barr Syndrome, discovered he was diabetic, and laid fallow at a ratty “welfare hotel” in Salem, Oregon), it seemed that he’d be remembered solely by folkie snobs and patcholi-reeking acid casualties. When City of Refuge (Tim/Kerr) broke his decade-long silence last year, Fahey, already bolstered by a 1994 Byron Coley profile in Spin, simultaneously pricked up the ears of the modern avant-garde community and pissed off most of his old constituency. While folks like Jim O’Rourke and Thurston Moore sang the praises of Fahey’s unique style (O’Rourke’s band, Gastr del Sol, covered a Fahey tune on 1996’s Upgrade and Afterlife), he paid himself no such reverence – most old-school Fahey fans were downright offended by the noise collages and experimental tenor of Refuge, while Fahey, a fan of bands like Einstürzende Neubauten as well as the folk, blues, and world music he grew up on, says without hesitation that it’s “the best album I’ve ever done.” The recent collaboration with Boston avant-improv collective Cul de Sac, The Epiphany of Glenn Jones (Thirsty Ear), almost didn’t happen: Oddly, it was the young anti-formalists who entered the project with preconceived notions of how it would sound, whereas Fahey kept chafing against their efforts to hem in the music to existing boundaries. When, after several frustrating false starts, Cul de Sac ceded control of the project to Fahey, the result is an album unprecedented in either catalogue. Spacious and cluttered, ambient and noisome, lulling and hilarious, it’s as full of strangely-appropriate contradictions as the man himself is.

To get ahold of Fahey physically is no simple 12-bar progression itself: Now living in somewhat better digs in Salem, where he paints, collects records, and records his sound collages, he’s not hard to find, but his newly-replenished energy seems to require that he not stay put. The interview that follows is pieced together from three different sessions, where Fahey, as unable to be pinned down on one subject as he is to stay in one place for any length of time, held forth on subjects ranging from the comparative value of Balinese gamelan records to Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. A sampling of the rambling wit and wisdom of the amiable curmudgeon follows.

This must be a very exciting time for you. There’s been such an enormous resurgence of interest in your stuff the last couple of years. And getting back to work after being ill for so long must be quite gratifying as well.

This must be a very exciting time for you. There’s been such an enormous resurgence of interest in your stuff the last couple of years. And getting back to work after being ill for so long must be quite gratifying as well.

Oh, yeah, I was getting sick and tired of laying around all the time. It gets boring to be worthless. I feel much better these days, though, making music and painting. I actually think I prefer the painting to the music. I can just sit here and churn ’em out at the rate of one every five minutes or so. The music takes a little longer.

Your music, especially on City of Refuge, seems to have taken on a much different tone than you’re known for…

More sinister, yeah. I wanted to put out records that had that kind of projection for a long time, but I didn’t think I could get away with it. I had thought the whole experimental music thing had kind of come to an end, but I heard what some people were doing in that vein a few years ago and thought, “Oh, I could do that. I could do that better.” And I think I did. That’s probably my favorite album of all those I ever made. That record should get a Grammy or something. I don’t know how well it’s selling, though. I imagine it might be selling rather well.

Especially now that your name’s getting bandied about a lot more.

Bandy, bandy, bandy, yeah. Well, I’m “comeback of the year” (in Rolling Stone), aren’t I? I don’t know what possessed them to say that, but I’ll take it. Anyway, I think City of Refuge is my masterpiece. You can put it away and come back to it, you can listen to it a hundred times and still get something new out of it. Which I don’t think you can say of the new record, I don’t know why.

Is that because of the circumstances behind it? It was an infamously difficult record to make, I heard.

It would’ve been worse if I hadn’t taken over, I think. You read those liner notes and you might assume I was wrong when I called them (Cul de Sac) a “retro-lounge act,” but that’s what they were! They were doing jungle music, you know what I mean?

I think so.

That’s what they were doing. So I fought and I fought and I fought, and finally I called up Thirsty Ear and told them I wanted nothing more to do with this. I didn’t want my name associated with it, and I told them I’d quit if they didn’t put me in charge, which they did. I tell you, I never felt so good in my life as I did when I walked in there and said, “Okay,cut!” and went and erased all those tapes. You have no idea how horrible the record would have been. But it ended up turning out okay, it’s a fun record. I especially like the recitations at the end, like “Nothing.”

That’s my favorite, too. Was that written out beforehand?

Oh, no. I’m pretty good at making those things up. I think the brilliant one on that record’s the synthesizer player, he was great. You take the synthesizer off the record, and you’ve got practically nothing.

Has this experience turned you off to the idea of collaborating?

No, not at all. I’m sure they’re gonna want to do another record with me, especially since this one’s selling so well. And that’s fine, I’d like to – and if I’ll have to be a bastard again, I will. It got to be fun, you know, after the explosion. But I’ve got other projects first – I did a record with Skip James that’s even more death-and-destruction than City, which doesn’t even have a title yet. I’m doing a light jazz album with a bunch of musicians from around town. And I’ve formed the John Fahey Trio – we just did an hour-long radio show locally that was really good. It’s fun to be so creative again, to be getting stuff out there at such a quick rate and to have the freedom to do what I want to do.

Weird how your old ideas are making their way back into the modern ear – the last couple of Jim O’Rourke records are so influenced by your earlier stuff.

Weird how your old ideas are making their way back into the modern ear – the last couple of Jim O’Rourke records are so influenced by your earlier stuff.

Jim told me he got into that ’cause he was just getting tired of standing on-stage with a bunch of machines, pressing buttons. It’s strange that he’s going acoustic, while I’m going the opposite way, more towards what he used to do. He’s a really nice guy.

What do you listen to these days?

Mostly myself (laughs). I’ve been making a lot of collages on tape, and I spend a lot of my time listening to those… but as for other people, there’s two concept records – one by Frank Sinatra, Water Tunes, and another by Van Morrison, Astral something…

Do you mean Astral Weeks?

That’s it. It’s a fantastic record, but I had never heard it before. I don’t suppose it sold very well, but it appears to be somewhat influential. I hope people think of my albums the same way, not necessarily making the top of the charts or whatever, but always there, always present. Uh… could you call me back in about half an hour? I’ve gotta take a shit and get some coffee.

(Half an hour, one bowel movement, and one cup of McDonaldland java later)

Much better. I took a little walk and collected my thoughts. I also took some Vicodin, so I might be talking a little slower. Now, where was I…?

Tell me about your living arrangements. I’ve heard a lot of stories…

The reason I moved out here to this hotel is ’cause – well, I lived in this other place, the Union Gospel Mission, for five years. It’s a big place, too, about 300 rooms – it used to be a Holiday Inn and now it’s a welfare motel. The woman that ran the place, (name deleted to avoid trouble), was always a good friend of mine, but she kicked me out because the narcotics, prostitutes, and crime there was starting to get ugly… I was getting scared, you know. People on the staff and friends of mine were starting to get hooked on stuff, some prostitutes stole 700 bucks from me… (The owner) had always told me to tell her about it, and I did, but nothing was ever done. Then, it turned out that there was a potential buyer for the hotel, and she told me to shut up and keep it quiet. Then I went up north to play some concerts, and while I was gone, she evicted me. Took all the stuff from my room and wouldn’t let me have it when I came back, and I’m still trying to collect it. My reapplication for health insurance got lost… I had some really bad luck, and it’s all because of her. I hope that place blows up or something.

Let’s move onto greener pastures – you’re getting new and different audiences than before. How do your current crowds differ from the ones you used to get?

Oh, they’re much better. They’re far more open to experimentation and they even stand up in front of me when I play. They don’t sit there, cross-legged and ask to hear my old stuff. When I get old farts trying to get me to play my old material, I tell ’em to get lost. I really try and distance myself from them, I don’t like to stay in one place… (calling off) Just a second, Marty! Come on in! I’m talking to a magazine! (to me) Hey, my friend’s here. Can you call me back tomorrow?

(The next morning…)

I have something to ask you and if you don’t wanna do it, that’s okay.

What’s that?

Well, I’ve been nominated for a Grammy, you know, and that’s a pretty big deal in Oregon. In any case, people will probably be calling me about it, not only that but calling other people about me. What I’m trying to do is get people to call the place where I used to live and simply ask the manager about me, just bring my name up to her, just to kind of frighten her. All we have to do is just mention my name a few times to her long-distance, and she’ll get scared. The way she kicked me out of there was not nice, and I’m still convinced it was because I wouldn’t keep quiet about the crime problem there. It doesn’t matter what you ask, just mention my name. I have on-campus spies, I’ll hear about it. That’d make me feel greeeeaaattt.

No problem.