Reverend Richard J. Mackin

Reverend Richard J. Mackin

The Captain Ahab of Spoken Word?

by Chad Parenteau

Prior to January, my encounters with Reverend Richard J. Mackin were limited to his Book of Letters series, his recorded performances, and an in-store signing at Allston’s Flyrabbit for his most recent Book of Letters #11 and This Place Is Weird, a collection of his artwork. Even so, it was easy to deduce that he is one of the least likely to hold back on words.

I was able to arrange a meeting at Bukowski’s to have a quick dinner and a long talk. To prepare, I went to Flyrabbit and bought Rev. Richard J. Mackin’s Book of Promotion, just one of many publications under his Evidence of Active Thought (EAT) imprint. Billed as “The Central Piece of The Rich Mackin Press Kit,” it contains a summary of his artistic career and a collection of reviews and articles on his books and performances.

Let the following interview show, if nothing else, that Mackin – still living in Allston and recently married to fellow artist and college sweetheart Dana Sibley – is by no means naive when it comes to his art.

We started right off with him talking on record about his documentary film in the works. Its genesis can be found in his first Book of Letters and heard on On Tour Without A Band, a compilation of performances put out by Mackin and his fellow members of the spoken word group 1-900-EAT-a-RedBackPack. It all started with a single question in his first book to the Lever Brothers company in New Jersey: Why was their soap called Lever 2000?

More letters followed, numerous absurd statements all carrying the same questions, some answered with the customary form letter, some not at all. Eventually, it led to a trip last March to the Lever Brothers headquarters in New Jersey in a failed attempt to talk with the consumer representatives. All this, in turn, led to this Roger and Me film gone awry. Tentatively titled The White Whale, Mackin told me it is near completion, and might be shown at the Coolidge Corner theater in Cambridge. Originally intended to be a opener for the waiting audience at the theater’s annual Sick and Twisted animation festival, the idea was rejected, “for numerous, very good, logical reasons,” as Mackin put it. “But they were so impressed with both our work and our presentation, that they were like, ‘Well, we’d be interested in letting you just use the theater.'”

More letters followed, numerous absurd statements all carrying the same questions, some answered with the customary form letter, some not at all. Eventually, it led to a trip last March to the Lever Brothers headquarters in New Jersey in a failed attempt to talk with the consumer representatives. All this, in turn, led to this Roger and Me film gone awry. Tentatively titled The White Whale, Mackin told me it is near completion, and might be shown at the Coolidge Corner theater in Cambridge. Originally intended to be a opener for the waiting audience at the theater’s annual Sick and Twisted animation festival, the idea was rejected, “for numerous, very good, logical reasons,” as Mackin put it. “But they were so impressed with both our work and our presentation, that they were like, ‘Well, we’d be interested in letting you just use the theater.'”

In addition to footage of Mackin’s spoken word performances reading his letters to Lever 2000 and their monotonous response out loud, the film will cover the trip he and friends made to the Lever offices last March. Half-seriously, I asked Mackin (who can recite the names of all of Lever’s Consumer Representatives from memory) if he thought he’d made an enemies list over there.

“I wonder sometimes. I actually did get an email recently from someone who works at Lever 2000, who’s not officially reacting to me but is just someone who happens to work there. He was like ‘I got your book. It’s really funny. What would you like me to do?’ That’s been too recent for me to actually take any action, but I was like, ‘Oh, I will definitely work something out with you.'”

“I wonder sometimes. I actually did get an email recently from someone who works at Lever 2000, who’s not officially reacting to me but is just someone who happens to work there. He was like ‘I got your book. It’s really funny. What would you like me to do?’ That’s been too recent for me to actually take any action, but I was like, ‘Oh, I will definitely work something out with you.'”

At first, Mackin told me the film was finished; but a few minutes later, told me he was considering revisiting the Lever Brothers offices again this March.

“That’s a real problem that a lot of my projects have. It takes me longer than I want to get around to actually presenting it. Just when I say, ‘Okay, I’m gonna put this together,’ something new develops, and I say ‘Oh, it’ll have to wait.'”

This project especially has gone much farther than anticipated, with no foreseeable end in sight. That’s part of the reason behind the film’s title. “A friend of mine from way back, who’s been keeping tabs on me, said that the Lever 2000 quest was like my Moby Dick, my never-ending search that will someday destroy me.”

Not that this has stopped him from thinking towards the new millennium, and the letters with futuristic themes he plans to write to Lever 2000 and similarly-named companies. “What’s gonna happen,” he pondered aloud for my sake, “with Twentieth Century Fox and Lever 2000 and all these names that used to sound futuristic and up-and-coming?”

\ Having gone into the foreseeable future, we backtracked a little into his high school years in Norwalk, Connecticut, or as he put it, his ascension from “nerd, to punk, to whatever the hell I am now.”

Having gone into the foreseeable future, we backtracked a little into his high school years in Norwalk, Connecticut, or as he put it, his ascension from “nerd, to punk, to whatever the hell I am now.”

“Like a lot of people I know, punk rock saved me from becoming whatever horrible thing I would have become,” said Mackin, who in his teens grew the spikes that can be seen in photos adorning some of his books and even the autobiographical comics he writes and draws. More importantly, he developed at a young age the mindset needed to be a publisher and promoter of his own work.

“I think one of the important things about the punk rock thing,” he pointed out, “above and beyond anything specific, [is] you don’t have to pay fifteen dollars to watch a rock band. You can go and interact with the band and the band can interact with you. There’s less of a difference between three guys who learned how to play instruments a little bit to have fun, and the big rock band that you’ve been waiting all year to see.”

“I think that kind of helped with the whole do-it-yourself ethic,” he added. “You don’t have to be making a living doing something. You can still do something just because you enjoy it. It’s valid.”

Even though he did well with drawing and writing in high school, later graduating form the Mass College of Art, there was never any set goal in Mackin’s mind.

“I’ve never really known what I’ve wanted to be,” he said. “I still don’t entirely, but I’m always narrowing it down.”

Still, he knew early on that college was a necessity to get on the path. “I knew that if I went to college, I could get out of a boring suburban town and do something better,” said Mackin, who admitted his large town was not particularly friendly to artists or conducive to creativity, unlike a city or even a small rural town closer to nature. “If you’re in a small city where there’s enough to keep you distracted but not necessarily enough to inspire you, that’s kind of a weird situation.”

The city of Boston, Mackin said, was far enough away that it was actually a more ideal choice than New York City. Although he describes the Big Apple as “the complete antithesis” to living in his Connecticut hometown, he and others from his area feel that it’s close enough to home “that you don’t really feel like you went anywhere.”

The city of Boston, Mackin said, was far enough away that it was actually a more ideal choice than New York City. Although he describes the Big Apple as “the complete antithesis” to living in his Connecticut hometown, he and others from his area feel that it’s close enough to home “that you don’t really feel like you went anywhere.”

It was in college, said Mackin, that he got involved with spoken word and the idea of, “poetry as something that’s not written by boring old men in little books that you read in the library.”

“I went to school to become a visual artist,” he said. “But at the same time, if I didn’t go to Mass Art, I probably wouldn’t be exposed to the things that led me to become the writer that I am.”

Mackin named influences in the world of fiction and non-fiction, listing Kurt Vonnegut, Abbie Hoffman, Tom Robbins, and Ward Damio, a lesser known writer who Mackin got to know from dating his daughter and whose true-crime book, Urge to Kill, was featured in the movie Serial Mom. He talked more at length about their similar styles. “When Vonnegut writes a fictional story, it’s usually not, ‘here’s a fictional story.’ It’s ‘Here’s a true story, about me, Kurt Vonnegut, writing a story that’s a work of fiction.’ Same with Tom Robbins every now and then. ‘Okay, after writing three chapters, I’m now just gonna discuss how I don’t really like this typewriter anymore.’ And Ward Damio also is like, ‘Here I am, writing this accurate book about something, but every now and then… I’m just gonna tell you what I think about this.'”

As far as the influences of his letters go, one might look to Don Novello, better known to most as the personality Father Guido Sarducci, more admired by Mackin as the writer of letters under the name Lazlo Toth. However, Mackin, who started after a reply from M&M/Mars to his simple questions about M&M candies, did not come across Novello’s work until after having written more of his own letters.

“For two seconds,” said Mackin, “I was like, ‘Aw, someone else already did this. I’m not that creative at all.’ But then it kind of made me think, ‘Well, that kind of validates it as an art form.'”

Mackin felt his own twist on the form was that he has never used a pen name. “For the most part, I’m writing as me, the guy who’s writing crazy letters, just at face value without any secondary motive.”

Mackin felt his own twist on the form was that he has never used a pen name. “For the most part, I’m writing as me, the guy who’s writing crazy letters, just at face value without any secondary motive.”

Not that this has stopped him from bringing up points he doesn’t necessarily agree with. “I’ve done a lot of work about junk food and candy being spiritually similar to unproductive sex,” said Mackin, who explained that this was addressed to right wing groups opposing things like birth control and homosexuality. “It’s because they are sexually for pleasure and not for procreation, so I drew the comparison: well, that’s like if you’re eating candy or gum. You’re eating for enjoyment, but you’re not getting any nutritional value.”

“I actually do think I have a point in terms of that,” he asserted. “In order to do that, I suddenly sound like I’m actually decrying all of these sexual actions, which I certainly am not; but at the same time, in order to not sound antagonistic towards some of them, sometimes you have to make it seem like you’re agreeing, whereas what you’re doing is completely making a mockery of them.”

Once in a while, there are those who catch on, such as GE (in book #6), who, Mackin recalled, “thanked me for taking time out from what must be a very hectic schedule. I very much liked that because, well, that was definitely insulting, but it was insulting me on the level that I’m working on, so that I very much deserved it.”

“If I am who I am, I get the joke, and I appreciate it back; but if I actually was that much of a crackpot and did this for my own diabolical interests, the joke would probably go right over my head and I wouldn’t realize I was just thoroughly insulted.”

Some get the joke but do not find it funny. The best example (seen in book # 11) is IBM, who received his question, “I was wondering, are you aware that this is a sentence? I BM. As in I, me, have to BM.” They responded not with a letter, but with a waking morning phone call this past Columbus Day, threatening to sue him. Unfortunately, Mackin, half asleep at the time of the angry call and half-realizing the situation as it unfolded, agreed not to send letters, leaving him to encourage others to create postcards with the same question and urge others to send them out. No additional threats have been given so far, but he isn’t worried. “If IBM sued me, that’d be some of the greatest publicity I could ever get.”

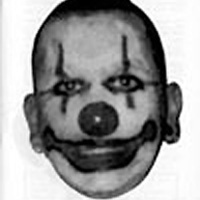

Several other trademarks include a picture of his face adorned in clown makeup, which was on the cover of the first book and has been reappearing ever since.

Several other trademarks include a picture of his face adorned in clown makeup, which was on the cover of the first book and has been reappearing ever since.

“Several years ago, I was a clown in a business suit for Halloween,” he said. “The idea of a clown wearing a tie just seemed very fitting, combining complete silliness with the weird corporate ethic involved.”

“And,” he added, “It’s good to have a logo. I’ve read three or four totally unrelated things in the last year about the band Sam Black Church, about how their little triangle-with-a-cross-on-it logo had helped their career. It’s not [just] because of recognizability, but you can certainly put this easy-to-print thing on coffee mugs, or oven mitts, or aprons, or anything, and suddenly, ‘Hey, cool. I’ll get a Sam Black Church tea cozy, and someone can come to my house when I’m making tea, and say, ‘hey, you’re into SBC.'”

Mackin also confessed to liking the self-promotion the image helps carry. “You’re not a egomaniac for saying, ‘Come see my band, it’s really cool.’ It’s not the same as, ‘Come see me, I’m really cool.’ But to do something where it’s pretty much you by yourself, you have to [say], ‘I’m really cool. Come see me. You want to leave your house and spend three dollars to sit and watch me talk for a couple of hours.’ So you have to [know] what’s being an egomaniac and what’s being a good self-promoter.”

His Reverend title, as he has been asserting in every other one of his books, is true. The title was given to him by the Universal Life Church based in California (which he has never visited), a religion based on the idea that everyone can become a minister and that you alone can determine your own beliefs. Mackin himself became ordained after sending in the “pocket change” fee for his license.

“I would say a good ninety percent, if not more, of the people that get involved with the Universal Life Church, do it because it’d be funny,” said Mackin, though he did point out that he finds something valid about its system. “To a great extent, it takes [the] American value that everyone has the right to determine what is good for themselves, and kind of makes it official.”

What’s less known is that in the addition to the “air of credibility” the title gives him, Mackin truly has the powers any reverend has.

“I can perform marriages, baptisms, and funerals,” he explained. “I have actually performed one wedding, in which the two people wound up getting divorced the next year. They called me up, and they were like, ‘um, that wasn’t legal right? That was just silly, right?'”

“I can perform marriages, baptisms, and funerals,” he explained. “I have actually performed one wedding, in which the two people wound up getting divorced the next year. They called me up, and they were like, ‘um, that wasn’t legal right? That was just silly, right?'”

Like Mackin’s image, the skills needed to print his own work also came piece by piece. Though his talents are more refined today, Mackin said he “haphazardously” learned the skills needed to start the magazine. “If you see the original drafts of a lot of my original books and then you look at what I do now, it’s just leaps and bounds.”

Mackin reasoned that it was his self-education with printing that helped him at Copy Cop, where he’s been for three-and-a-half years. “As a general rule, there’s no real reason why anyone would take a great interest in photocopying. But when I was still in school, I lived next door to the Staples in the Fenway, and I was at the copy center there virtually daily doing one project or another.”

For those who can see the convenience of a self-publisher working at a copy shop, Mackin told me it was all coincidence. “I kind of fell into it. Once I started working there, there were certain opportunities available, and I said, ‘Hey, this would be a job I wouldn’t mind doing.'”

Mackin is just as involved in numerous projects as he was in college – working with fellow spoken word performers, working on making the movie as multi-faceted an event as possible, and being the main organizer of Beantown Zinetown 2 (March 28 at the Mass College of Art).

“I like to throw things together,” he said, “that on the surface aren’t necessarily the same thing, the same format, but on a deeper level, actually have a lot in common.”

His writing these days can be seen to have that same mixture. In addition to his letters, his Flipside magazine column “Sucker Punchline,” and his new Lollipop contribution, he is also doing an article for the magazine Art Collector International, which will tackle the “myth” of going to art school to become an artist.

One reason, Mackin said, he was compelled to do more writing after college was its easiness to store. “It’s the content that’s more important than the physical letter; and it’s a lot easier to get five-hundred people to buy a two dollar ‘zine than it is to get one person to buy a thousand dollar painting.”

One reason, Mackin said, he was compelled to do more writing after college was its easiness to store. “It’s the content that’s more important than the physical letter; and it’s a lot easier to get five-hundred people to buy a two dollar ‘zine than it is to get one person to buy a thousand dollar painting.”

When I asked Mackin how he’s profited from his work, he related a conversation with his friend Mark Reusch, illustrator for a number of Boston publications, Lollipop included.

“He said he feels kind of bad when friends do great big paintings [and pay to] hang and store them,” said Mackin, “when he does all these 11 x 17 things on cardstock and just mails in a copy [to the publication]. They pay for the right to use it, but he still has all the physical stuff. He still owns it all.”

“That’s kind of where I am right now,” he noted, “I’m not making lots of money, but I’m not spending lots of money.”

An ideal project for the future is to collect his letters into a larger, easier to promote book titled Dear Mr. Mackin. “It’s not so much that I want a big grown-up book,” said Mackin, who explained that the book would merely be an easier item to sell to bookstores and give to libraries.

A project closer to completion is the third issue of Protests Are Your Best Entertainment Value (PAYBEV). In issue three, Mackin will definitely be featuring the Church of Euthanasia and either focus on their presenting a “Litter A Park For The Earth” during the last Earth Day festival, or his handing out smoking literature during a pro-life rally while the Church of Euthanasia held a (mock) fetus barbecue with the sign “Eat A Queer Fetus For Jesus.”

Mackin found it hard to explain the Church of Euthanasia, falling back on calling them a “street theater” group with “bizarre props.” It seems that in some ways, they baffle him in the same way he baffles consumer representatives. Although not condoning everything about the church, Mackin acknowledged their power to lure a crowd.

“Holding a small sign saying something logical does not necessarily draw the attention of having a banner saying something illogical,” he admitted. “If I were doing something, and I could get the Church of Euthanasia to show up, even if they were totally unrelated, I would, because they get attention.”

“Holding a small sign saying something logical does not necessarily draw the attention of having a banner saying something illogical,” he admitted. “If I were doing something, and I could get the Church of Euthanasia to show up, even if they were totally unrelated, I would, because they get attention.”

While the Earth Day protest merely focused on the hypocritical act of leaving the park a mess after the festival, Mackin dealt out more poignant information during the pro-life rally. His flyers illustrated a study showing that a great number of stillborns were caused by mothers smoking.

“No one expressed any interest in that whatsoever,” said Mackin. “There are these people every week, out in front of clinics, and even places that do abortions aren’t just abortion places. I found it ironic that there’s so much focus on that. If you’re going to think of the unborn child as an innocent baby, why is it okay for the tobacco industry to kill thousands of innocent babies?”

We talked for almost an hour and a half, and not once did I really focus on his comparatively smaller role as a visual artist. Neither had he gone out of his way to bring it up. No better time to bring up the question of how it feels to be more recognized as a writer than a fine artist, or a cartoonist, or even an illustrator.

“It’s ironic, but not disappointing. The thing I find ironic is that I know people who went to college who learned to be writers who are now the managers of a Starbucks or something. What I’m doing has very little to do with what I intended, but at the same time, I’m still doing creative things. I still have an outlet. I’m still drawing attention to myself. Certainly it’s not the main reason, or the secondary reason; but it’s nice to go and have people say ‘Hey, you’re cool. I like what you do.'”

Mackin’s work can be found in Flyrabbit, Garage Video, Smash City, Nuggets, Tower Records, and on request at The Revolving Museum. Mackin can be reached either through snail mail at PO 890 Allston, MA 02134, email at richmackin@earthlink.net., or his website at home.earthlink.net/~richmackin/.