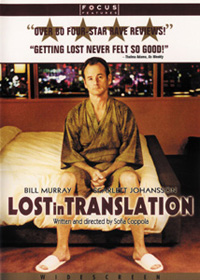

Lost In Translation

Lost In Translation

(Universal)

by Chad Van Wagner

Occasionally, a film with an artier-than-normal concept hits the jackpot, and gains boatloads of well-deserved accolades. That film then makes its way into the mainstream of America, who then react to it with a self-conscious (and often concealed) incomprehension. Non-film geek people (in my personal experience, anyway) are afraid to say that didn’t like what the critics thought was one of the best films of the year, and they end up saying things like “it was OK,” or a noncommittal “yeah, I liked it,” and hope the subject drops.

So, why am I talking about the reaction to a film, rather than the film itself? Because Lost in Translation is about this exact same go-through-the-motions disconnectedness. Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson play two well-off Americans stranded in Tokyo without anything to do, other than cling to each other as their lives seemingly go on without them. The location is Tokyo, but it might as well be Siberia: Japanese culture exists in the film simply to bewilder the protagonists, and bewildered they are.

Murray and Johansson play off each other perfectly, and director Sofia Coppola masters the balancing act of making the city seem welcoming when the characters are together, and ominous and empty when they’re not. Which brings us to the irony of the first paragraph: How often does a film’s “message” spill over (albeit inadvertently) into real life itself? Lost in Translation is a film that displays what happens when you politely do what’s expected, regardless of whether you “get” it or not, a point which is mirrored by many people’s reaction to the film itself. In this way, and many others too numerous and complex to get into in the space allotted here, Lost in Translation really, truly is a reflection of our society. If this seems like a stretch, you haven’t seen the film. This is the mark of a true artist: The film resonates beyond even the director’s intent, not because of dumb luck, but because it says something so straightforward and universal that all it needs is a spark to catch fire in a big way.

While it’s obviously silly to suggest that anyone who didn’t care for the film has the kind of issues Murray and Johanssen display here, the people who “don’t know what to think of it” (as more than one person has told me) might do well to see it again.

(www.universalpictures.com)