Dogshit Park

Dogshit Park

Part Two

by Todd Brendan Fahey

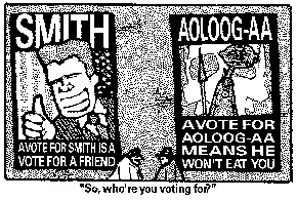

illustration by Rich Mackin

“I’m not home,” he said, shaking his head. No way. I picked up the receiver. It was Paddy. I looked at my watch, and saw that it was also 2:38 a.m. “Everything alright?” I wondered. “Oh, sure,” the old man chuckled. I could hear the ever-present music pulsing through his Nakamichi system. It sounded like the Allman Brothers at one of their early ’70s Fillmore gigs. “I hope I didn’t wake you.”

“No. I’m just up talking to my roommate. Do you need something? Do you need me to come over?”

“No,” he laughed, brittlely. “It’s… I was just wondering…” he said, taking his time with what it was he wanted to say. “Just something that stuck in my mind. I was wondering what might have set your friend off. The one on the cannery rig: Marcus, was it?”

“Yeah,” I said, becoming edgy, because I knew Paddy would forget Marcus’s name no sooner than he would forget his own: the old man had a mind like flypaper. It caught everything, some of it useful, most of it flotsam; but he kept all of it stored upstairs, to use someday, when he felt like writing again. As he told it, what motivation the Hodgkin’s hadn’t stolen, the chemotherapy took care of neatly. He hadn’t written a story for nearly two years, and had been placed on an extended medical leave of absence by USC, his salary halved, but his job guaranteed until he felt able to return to full-time teaching. Until then, he convalesced beside the beach, taking on a few especially promising graduate students whose writing he coached and guided and polished for inclusion into the literary magazines, the “littles,” as they are called by those who find homes in them.

I was not among the lucky.

Promising as my work appeared to the Professional Writing faculty, I owned enough rejection letters to spark a heinous fire at the houses of any of the individual editors of the hundred-odd “littles,” on which I had wasted $.74 a pop in postage over the course of more than a year.

“Hang on a minute, Paddy.” I cupped the mouthpiece and looked over at Scott, who was now the proud owner of a seam-splitting grin. “Can you make it another couple minutes?” I wondered. “It’s my writing teacher. I can’t tell what he wants.”

Scott nodded squarely, succumbing to the recesses of the sofa. “No problem. Take as long as you need. I’m not going anywhere.”

I nodded, releasing my hold on the receiver. “What happened to Marcus?” I repeated, finally.

“Uh-huh,” Paddy answered, breathless.

I sighed. “Our freshman year in the dorms, he decided he wants to see other girls, legitimately, without having to sneak around. He had been dating his high school sweetheart for a long time, but her parents sent her off to a Catholic college in Nebraska. So he wrote her a letter, at least he told me that’s what he had planned on doing. He wanted to tell her in person, but Christmas break was four months away, and he just didn’t want to string her along. He loved her, but it was over,” I said, dredging up the putrefied foot-locker. “The gal took it really hard, and then she stopped writing. A few weeks later, Marcus’ mom called him at school. We were playing backgammon and drinking Scotch in his room, and I’ll never forget it. His face aged ten years. He didn’t say much, just hung up. Then he put the cork back in the Scotch and we finished playing backgammon until the sun came up. He wouldn’t let me leave. After that, he would stay in his dorm room for days. I would bring him food from the cafeteria, and we drank and played games and got to be really close friends. But I was the only one. He was shattered.”

“What did she do?” Paddy said. The music in his living room had gone off.

“She slit her wrists over the kitchen sink,” I said. I was shaking uncontrollably; it always happened when I talked about Marcus, which I hadn’t, to anyone, in a very long time. They found her the next morning. She’d deadbolted the door. They had to use the master key to get in, a waste-paper basket was filled with used kleenexes.”

“Any note?” Paddy wondered.

I shook my head and breathed deliberately, trying to regain composure before Scott. “No note. She burned a letter in an ashtray, but they couldn’t tell who it was from. The envelope was on the table, though. It was still intact.”

“Who was it from?” he said, but actually it was more of a demand.

“Marcus said he didn’t know. He changed the subject when I asked him about it, and I’ve never had the heart to ask again,” I said. “But it’s fairly obvious, isn’t it?”

There was a long silence on the other end. Then the music came beating back through his system — a Big Band sound, or maybe Broadway show tunes — it was hard to be sure.

“I’ll see you Tuesday morning, won’t I?”

“See you then,” I told him, and hung up. I could tell just by looking that Scott had been adopted into the Tribe in my absence, christened by St. Leary himself. “How’re you doing, pro?”

“Screaming down the vortex!,” was his thunderous reply. His eyes were moist, as if he were bearing witness to something beautiful, and his natural wonderment made me mostly forget about the phone call.

For the next two hours, he sat on the couch, saying very little, his face contorted by a grin that appeared to be permanently sculpted into his facial elastin, while I sat in my reclining writer’s chair with the scuffed wooden arms, about five feet away, combing the grey fissures of my addled brain for any number of weird anecdotes that I knew would make us both howl like jackals until sunrise ushered in its own harsh realities.

At four-thirty, he began to level out, displaying signs of confidence. “Let’s go upstairs and look at my stuff now,” he said, his eyes glittering like neon signs.

I was only too happy to get up and unlock my spine, which seemed to have atrophied suddenly. We walked up to Scott’s bedroom, which was heavily decorated in a sort of Hindi-Japanese: a lot of bamboo and pots and woven textiles, which trapped the lingering scent of incense that he explained he burned ritually each morning before leaving the house. His artwork, mostly airbrush portraits of women, reminded me of Nagel, only less deliberate. They were exquisitely good, and I told him so.

“Why don’t you show these things?”

He shrugged and kicked at the ground with a socked foot. “I tried once,” he complained, “but my art teacher in junior college hated them. I think she was a lesbian. She just couldn’t stand anything I did. That’s why I dropped out of school. That’s why I’ll never get promoted,” he said, and I caught him before he wound himself into an irrescuable loop.

“I’ve got a friend whose parents own two galleries in Scottsdale. I guarantee you can unload five of these a month. This stuff’s great,” I said, admiring the alien cobalt-and-rose of one of the pieces.

We sat upstairs, listening to Kate Bush for the rest of the night, talking about Scott’s erstwhile-girlfriend, who used to share his very bedroom, but who was now suffering from candida, a bizarre aversion to yeast that he claimed transformed her over a period of months from a mild, sex-crazed thing of utter perfection into a screeching nut. He showed me a couple topless photos he had taken of her with a Polaroid the previous summer, and I had to agree she looked like an angel.

At 5:45, the door of the other bedroom opened quietly and a bearded man in his early-forties popped out, clad in leather riding gear. “See y’,” he said, in a clipped Welsh accent, and walked down the stairs and out the front door. Out in the carport, we heard the sound of a motorcycle sputter to a start, then roar away.

“We don’t see much of Jeremy,” Scott shrugged. “I moved in five years ago, and he’s been here about three-and-a-half. He’s kind of like you were. Are… I guess,” Scott muttered, realizing that before midnight, he had never spoken ten words to me, aside from the interview, and at nearly dawn, we had become brothers in some strange, psychedelic way. “Were you ever going to get to know me?” he wondered.

I shook my head. “I took a weird job last month: as a technical writer for an aircraft company that does work with the Defense department. It’s a ten-hour shift, and we’re not allowed to leave the hangar. Everyone eats at the cafeteria. But it really works out to about three hours of work and six hours of writing time. I come back here and stay up all night typing those yellow pads into the hard drive,” I said, pointing downstairs, at where a pile of handwritten yellow paper lay next to my computer. “But then you came downstairs tonight and fucked everything up.”

We both laughed, but mine was more from nervous exhaustion. It had been more than thirty-six hours since I had slept, and my heart was starting to fibrillate. “I’ve got to crash.” I saw the pained look on Scott’s face, but there was no other way. “You’ll make it. It’s been fun,” I said. “We’ll have to do it again soon.” Then I walked downstairs and dismantled my liveaboard sofa and went comatose on the flimsy mattress.

I didn’t see Scott for the next few days, but when I did, he told me that he had seen me that night, after the LSD had taken hold, as some kind of tribal figure whom he called King Storyteller, and that the perfect spectrum of colors trailed out of my hands when I spoke, and that it had been one of the most entertaining nights of his life. He also said that he had worked through all of his problems with his family after I had gone to bed, and had even forgiven his father for molesting his younger sister; something he thought he would never be able to do.

That Tuesday, Paddy said he had discovered what was wrong with my fiction; it was something I said on the phone the night he had called so late. “The kitchen sink,” he chuckled. “Throw it in. You’re too spare. Add the goddamn kitchen sink. If that won’t do it, I give up.”

It turned out he was right: a mass-mailing of stories to thirty “littles” netted three letters of acceptance. Two from fairly new publications out of Illinois, the other from a venerable rag in Tennessee.

Scott met the news indifferently. We had gone on a couple more chemical Tours of Duty together, including a disastrous morning drive to Malibu, after I convinced him to call in sick to work. I had been operating on nearly two days worth of adrenaline, and wasn’t feeling real sharp to begin with, but Scott insisted that I stay up all night with him anyway. By the time the sun had come up, I had caught a second wind and felt the need for the breeze in my hair.

We sailed down to Malibu, listening to Steely Dan, and somehow found ourselves at the breakfast table of a roadside cafe near Pepperdine campus, seated next to Rod Steiger, who looked like he weighed in at least three-hundred pounds and who resonated a palpably heavier vibe. The actor was eating oatmeal and pitted prunes, talking about investment strategies with a pony-tailed freak whose hair was as long and gray and scraggly as his own.

Scott kept his sunglasses on for the duration of breakfast, fruitlessly trying to avoid eye contact with Steiger’s breakfast companion, who had caught wind of our conspiracy and was smiling and nodding at us in an animated sort of way. At one point, Steiger became irritated by his friend’s sudden inattention, and turned around stiffly and bellowed, “Well, why don’t you just fucking ask them to eat with us?!”

It was then that Scott fled, walking out to his convertible Alfa Romeo Spider, on which he still owed over ten grand, leaving me behind to pick up the check. We said nothing to each other on the drive home.

I worked the swing shift that evening, riding the rail of chemical insomnia for over fifty hours before the switchmaster sought mercy on my soul. After that, I saw Scott less and less. But one night, he came thundering downstairs to tell me never to adjust the thermostat again; that he “felt like a baked turkey,” and that he would control it for the household from then on.

Sometime the next week, he left a bitter note on the breakfast table, telling me to clean up the crumbs around the sink the next time I decided to make toast.

I saw him only once more — after discovering his airbrush and canvasses carelessly packed in a box in the rafters of the carport — and I remember the day well, because it was also the last time I ever walked through Dogshit Park. On a tip-off from Preston, I headed over to the storage sheds, then watched a sacred ritual turn sour: Scott shaking hands with Johnny.

After that, I moved down to Los Angeles and got married, finishing the Master’s degree at USC, where I learned that Paddy O’ Hearn had been fully recovered from Hodgkin’s disease for at least two years, but that his agoraphobia was so acute the school didn’t know if he would ever be back full-time.

$$$

Todd Brendan Fahey is author of Wisdom’s Maw: The Acid Novel and Hell Bottled Up!: Chronicles of a Late Propaganda Minister (www.fargonebooks.com)